Blog Archive

Today’s Other Half

Monday April 28th, the Museum’s Tenement Talk series will host a conversation about poverty past and present, and ways this country has responded to it (information here). New York Times columnist Ginia Bellafante will moderate a panel with journalists Sasha Abramsky and Ted Gup, and historian Ethan G. Sribnick from the Institute for Children, Poverty and Homelessness. The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) is a New York City-based think tank focused on the impact of public policies on poor and homeless children, and has written the following post on the history and current status of income inequality in New York City.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries in New York City, most poor families lived in unsanitary and overcrowded tenements. Poor air quality, lack of sufficient space and light, lack of plumbing and fresh water, and other defects bred sickness throughout the tenements. For decades, reformers tried to improve New York City housing with stricter regulations and requirements.

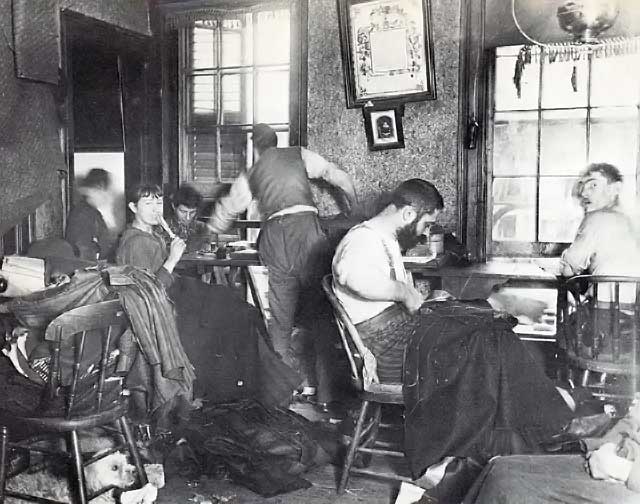

"Knee-pants at forty-five cents a dozen--a Ludlow Street sweater's shop," from How the Other Half Lives, 1890. Photo by Jacob Riis.

Social reformer and documentary photographer Jacob Riis was one of the most influential observers of these New York City slums. Rather than blame the poor for these deplorable conditions, he asserted that the environment itself contributed to poverty. Prior to this, the dominant belief had been that poverty stemmed from flaws in the poor themselves, however, the Progressive era challenged this perspective by examining how structural economic factors often created poverty, and how the environments in which the poor lived and worked perpetuated that poverty.

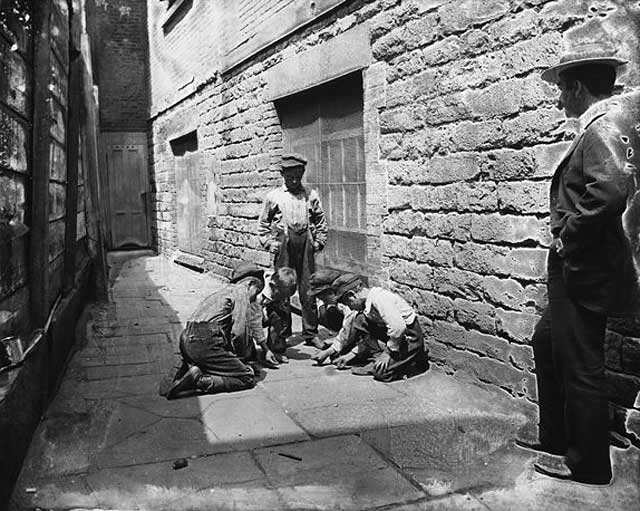

"Bandit's Roost," from How the Other Half Lives, 1890. Mulberry Street, where this photograph was taken, was one of the most dangerous parts of the city. Photo by Jacob Riis.

Riis wrote two books, How the Other Half Lives and The Children of the Poor, which remain two of the most detailed and popular accounts of poverty in New York. In them, he describes a world invisible to many; one in which families crowded into tenements, exposing themselves and their children to filth and disease. Stark photographs dramatically illustrated the destitute conditions in which too many families lived. Through these journalistic efforts, Riis revealed the conditions of the tenements to the middle class and popularized the belief that reform needed to begin with the environment. The overarching sympathy with the struggles of poor families struck a chord with the middle class and initiated a movement for meaningful tenement reform. These were human beings, Riis made clear, striving for dignity in an undignified environment.

Soon after, a social worker named Lawrence Veiller decided that to achieve much needed housing reform in the face of opposition from the city’s powerful building interests, he needed to display data for the public to view, describing an undeniable need for housing reform. He held an exhibition of carefully curated information to demonstrate the extent of New York City’s housing problem. This was among the first efforts to use documents, data, and photography to push for change. In the two weeks the exhibit was open, it was visited by 10,000 people, and later traveled to other cities around the country. The media attention garnered from the exhibit elicited a quick response from the governor and eventually led to the passage of the Tenement Act of 1901.

"5 Cents a Spot," from How the Other Half Lives, 1890. Each of these men paid five cents to sleep on the floor of this tenement on Bayard Street. Photo by Jacob Riis.

Similar journalistic efforts are still successful today. A recent New York Times piece by Andrea Elliot documenting the life and struggles of a 12-year-old girl living with her family in a decrepit city shelter outraged the public and brought family homelessness to the forefront of the national conversation. News outlets across the country began discussing the soaring population of homeless families, both in New York City and nationally. Actions were taken to move over 400 children and their families out of two city-run homeless shelters that had been repeatedly cited for poor conditions, one of which was featured in the Times piece.

The ability of research, data, and analysis to spur changes in public opinion and policy is at the heart of the work done by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH), a New York City-based think tank focused on the impact of public policies on poor and homeless children. The work presented by Riis, Veiller, Elliot, and many other journalists and researchers sparked meaningful reform for the forgotten poor.

Today, families in cities across the United States still confront decrepit and unsafe dwellings and overcrowding as they struggle to find places to live. Researchers today, such as ICPH, along with advocates, understand the importance of documenting social conditions and, even more crucially, of using social documentation to raise public interest. This strategy can still succeed in changing public policy and improving housing conditions for America’s struggling families.

For more information on the history of family poverty and homelessness in New York City, visit PovertyHistory.org. To learn more about the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness and our work, visit our website.

– Posted by the Staff of the Institute for Children, Poverty and Homelessness