Blog Archive

The Paper Chase

A toy doll’s head found in the ceiling of 97 Orchard Street. Just one of the many objects the Tenement Museum has discovered over the years.

One of the unique things about the Tenement Museum is the ordinariness of the stories we tell. Visitors can imagine what everyday life might have been like for the people who happened to live at 97 Orchard Street, people who were never famous, or terribly rich, and had no expectations of becoming history lessons. The apartments are set to appear as they might have while residents were living in them – tidy homes stocked with useful objects and small treasures, arranged to appear as if the residents had just stepped out and might return at any moment.

Because of this, there are few opportunities to display the hundreds of objects that were found in the process of restoring the building, discovered under floorboards, in the closets, tucked into mailboxes, or packed into mouse burrows. Because they can’t be placed into apartments, many duplicate objects and those in poor condition are stored in the museum’s archive. The archive holds hundreds of objects: bottles, food packaging, bone fragments, and a large collection of dismembered dolls. Very few are valuable in and of themselves; if they weren’t found in a National Historic Landmark building, most of them would have ended up in the trash.

One of the most common found objects in 97 is paper. The museum’s collection contains scraps of newspapers in multiple languages, pages from books, advertisements, packing paper, and undelivered mail. These scraps and pages are fascinating specifically because no one intended to preserve them. They’re missing words, have water damage, and are sometimes unreadable. Some have lost corners to mice. The papers don’t reveal anything earth-shattering – there are no famous names or important facts – but they can help us do what the Tenement Museum does best: get a glimpse into the everyday life of ordinary people.

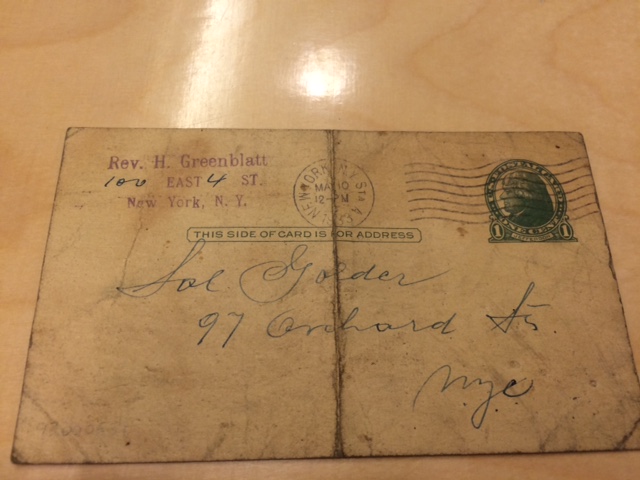

What can one of these objects tell us? One of the pieces of paper that resides in the permanent collection is completely intact, a small card – about 3.5 by 5.5 inches – with writing in Yiddish and an address in English. It was discovered in the kitchen of apartment five, tossed on the floor next to the east wall, in a pile of paper and trash. The postcard is addressed to Sol Golder of 97 Orchard Street, one of the people we know lived in the building, thanks to voting records. Sol was born in Romania in about 1872, and, while we don’t know when he immigrated, he was living at 97 Orchard Street by 1929. He lived at 97 with his wife, Nettie, and his two daughters, Sophie and Rosie.

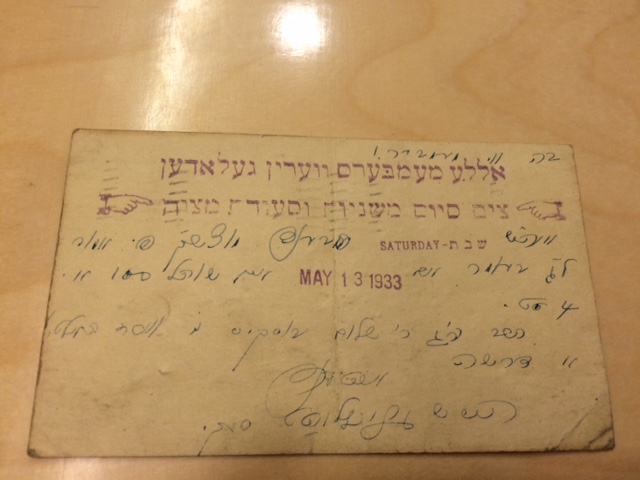

Postcard from 1933 found at 97 Orchard Street

Sol’s postcard is yellowed and worn, folded down the middle. The back shows two lines of Yiddish writing, stamped in purple, and a date: “All members are invited to a siyum mishnayos (a celebration marking the completion of study of a book of the Mishna, or oral law) and a festive meal, Saturday, May 13, 1933.” The card also contains a handwritten note in messy Yiddish script, creeping around the printed words to confirm the details of the afternoon. According to the return address, the postcard came from Congregation Bar David, at 100 East 4th Street, nearly three quarters of a mile away from 97 Orchard Street. Sol would have had to walk by dozens of other small synagogues on his way to Bar David – some in big stone buildings with stained glass and permanent seats, and some in the back rooms of shops or small apartments that served other purposes when services were not in session. In fact, his was one of over 17 synagogues of one sort or another located in a one-mile stretch of East 4th Street alone. Why did he pass by so many other synagogues on the way to his? Were the congregants mostly people from his home city? Or did they share a profession? Perhaps they had previously met on Orchard Street, closer to home, but had to relocate? Or perhaps it was Sol that relocated from East 4th Street years before?

The siyum was scheduled for Saturday, May 13, 1933, an inauspicious time for the Jewish community. Only days before, Nazis had begun public book burnings in the streets of Germany, and hints of Hitler’s extreme anti-Semitism were in the air, both in Europe and in the U.S. While Sol and his neighbors would have no reason to suspect the scale of the devastation to come, they were almost definitely aware of Hitler’s rise to power and the difficulties it was presenting to German Jews. They’d likely been approached to join the movement to boycott German goods, centered in New York City. Would the events across the ocean be a subject of conversation and concern in the midst of the festive meal? Or would attendees studiously avoid the topic, hoping not to spoil the atmosphere?

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the postcard is the return address: the invitation was sent by a Reverend H. Greenblatt. Why was a reverend sending out mail in Yiddish on behalf of a synagogue? And why does his return address stamp have blank spaces to fill in the street number and street? Though rare today, there is a long history of Jewish reverends. The title first became popular in England, where a two-tier Jewish education system ordained reverends as a sort of paraprofessional, with fewer requirements and years of study than rabbis. When the title migrated across the ocean to America, however, it wasn’t tied to any particular degree. Anyone could begin calling themselves “reverend;” the title was frequently adopted by religious functionaries who took the place of rabbis, often with little formal training. In the 19th century, many of these Jewish reverends were itinerant preachers who ministered to small groups of Jews on the frontier. By the 20th century, many congregations used the title to refer to those who carried out essential tasks in the synagogue – those who were responsible for the public reading of the Torah, or the shamash, the sexton who might have been responsible for the day to day operations of the synagogue, everything from replacing lightbulbs and locking doors to making sure that members received important notices and mailings. Most likely, Reverend Greenblatt was Congregation Bar David’s shamash, and with a return address stamp that let him fill in a different synagogue address on each piece of mail, it’s possible that he was the shamash for more than one congregation, allowing him to cobble together a full salary out of the small amounts he would have been paid by each synagogue.

Did Sol go to the siyum? Who was Reverend Greenblatt, anyway? What was for dinner at the festive meal? A single sentence invitation, stamped on a worn postcard, can offer plenty of hints about life on the Lower East Side, and reveal details of the day to day that we would never have time to go into on our tours of 97 Orchard Street. But at the same time, this small sheet of paper, tossed aside and ultimately buried in the rubble of a condemned apartment, leaves us with more questions than answers.

- Post by Rachel Feinmark, Strategic Communications Manager at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum