Blog Archive

Ruined, but not Destroyed: The Beauty of Disuse in an English Castle and our New York Tenement

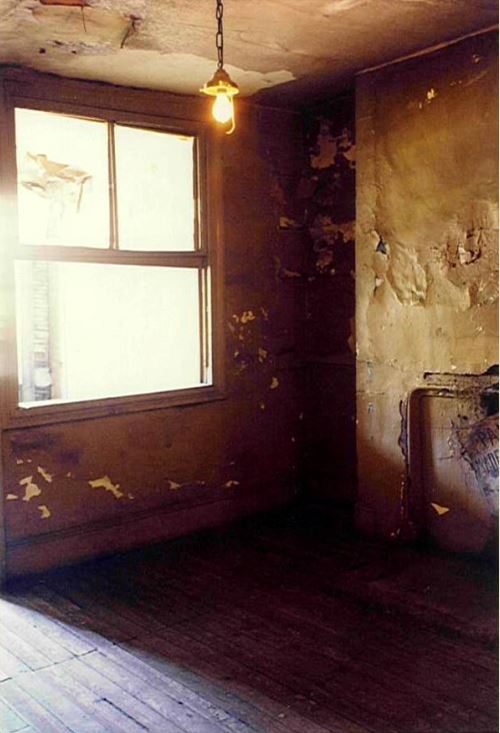

The 'interior' of 13th century Astley Castle. Gutted by fire, neglect, vandalism both natural and man-made, before the preservation. Photo courtesy of the Landmark Trust.

And we thought our tenement was old… what does a 13th-century castle have in common with our Tenement Museum in New York City’s Lower East Side? There is a lot to be learned from decay.

For some Museum guests, it is not the Tenement’s restoration but the deterioration that is the most exciting part of the visit. There are some spaces in 97 Orchard Street which the Museum has elected to maintain as “ruins” – spaces that have been kept pretty much as we found them when the building was discovered in 1988, after standing empty for around 50 years. For some visitors, these ruined spaces can say as much as the restored apartments about the hardship and joys of the former tenants, the importance of memorials, and the passage of time.

True, ruins serve all of these purposes, but they would be less successful if they didn’t look so wild, as though the visitor had happened upon this pocket of history in 21st-century Manhattan. In reality, the ruined spaces had to be cleared and secured, plaster restrained, and the walls reinforced just as elsewhere in the building. Preservation in the ruined was executed in a way the visitor could maintain his or her sense of discovery.

This sense of discovery is what connects our Tenement in New York City with a ruined castle in Warwickshire, England, which has just been rehabilitated by the Landmark Trust to be a dwelling again. At first glance, these spaces and their purposes couldn’t be more different. The castle has been attended to in part because of its illustrious history. In a ranking devised by Landmark bureaus in the United Kingdom, Astley is a “grand II” because of its connection to three Queens of England. By contrast, we preserve the Tenement in part because the people who lived there were not powerful, and their stories can often be ignored. However, the thoughtful efforts of the Trust in dealing with the castle emphasizes the importance of ruins in telling stories about history, just as we do at the Museum.

The Castle was built in the 13th century, although the Landmark Trust makes sure to note that it is, “strictly speaking,” only a fortified manor, not really a castle. Astley was crenellated (fortified) and given a moat in 1266. Monarchy was long the hottest ticket in town and laws of succession were carefully studied by aristocrats who might be eligible to become sovereigns. One of the Dukes who lived at Astley tried to put his daughter on the throne. Her rule lasted only nine days. She and her father were arrested and beheaded for treason. (The Duke was searched out and found in a hollow tree on his castle grounds.) Over the centuries however, Astley has fallen into disrepair. So, unfortunately it seems, it is not as easy to keep a castle as you might hope. The buildings were refurnished for rehabilitating soldiers during World War II and turned into a hotel after that. When a fire gutted the structure in 1978, keeping the castle upright seemed an almost impossible task.

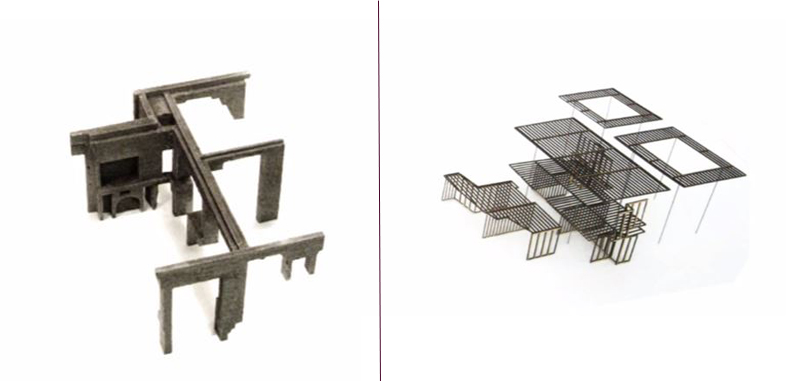

Images of the structures inserted in to the ruined cavities of Astley Castle, which both fortified the ruins and created a new dwelling space. images courtesy of the Landmark Trust.

Finally the Trust held an architectural competition in 2005, when the firm Witherford Watson Mann devised an ingenious plan for bolstering the structures that were near to collapse without upsetting the feeling of the ruin. The firm inserted a structure within the cavities of the collapsed building, very much like a rotten tooth, according to the architects. The new structure supports the original brick work, and visitors can stay in the original castle spaces but with the pleasures of a modern conveniences. From within the cavities of the castle, the view is much like that of standing in the ruined space. Only modern technology, a technique called Syntec drilling, has reinforced the crumbling stone walls. Syntec drilling is a patented system using a non-percussive diamond headed drill, which is low risk to the stonework. The channels made by the drill are filled with a special compound and in Astley’s case, five-ton lintels were crane-lifted over the moat to help secure the structure.

The Landmark Trust in effect gives history back to the people in a way which is very similar to that of the Tenement Museum. Sure, Astley was once a great hall fit for a lord and his retainer, but today anyone can rent the structure, which sleeps eight. If you were to fill it up with friends or family the price for the individual comes to £27.22, currently about $41.45. A small price to pay for a date with history.

A view of the preserved castle that shows the interplay of new and old stonework in the ruined structure. Photo courtesy of the Landmark Trust.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator.