How does a place become a federally-protected site of national significance?

In 1991, during the excavation for a General Services Administration federal government office building, at the corner of Broadway and Duane Streets in Lower Manhattan, workers made a monumental discovery. Under roughly 25 feet of city infrastructure, they unearthed hundreds of human remains.

The construction had revealed the first burial ground for free and enslaved Africans in New York. While known to historians, this area of approximately 6.6 acres, holding over an estimated 15,000 people’s final resting place, had never been physically uncovered. After over 400 people’s remains had been disinterred, a concerted effort from New Yorkers and descendant communities demanded that General Services Administration halt the construction and pay full attention to this discovery. A 10-year research effort, and the accompanying public activism for the project, would fundamentally change New Yorkers’ understanding of enslavement in the city and the critical role that people of African descent played in the early colony and nation.

As research began on the site, hundreds of descendant community members and concerned citizens created a grassroots campaign to advocate for honoring the spiritual importance of this land. They asked for the burial ground to be officially preserved and recognized, and to be included in updates and decisions about what would happen to this sacred site. They found they needed to fight for their voices to be heard, and petitioned city and federal officials, many of whom became involved in supporting the cause–Mayor David Dinkins and State Senator David Patterson both helped form public committees to oversee and report on the project, and hold GSA accountable to the community.

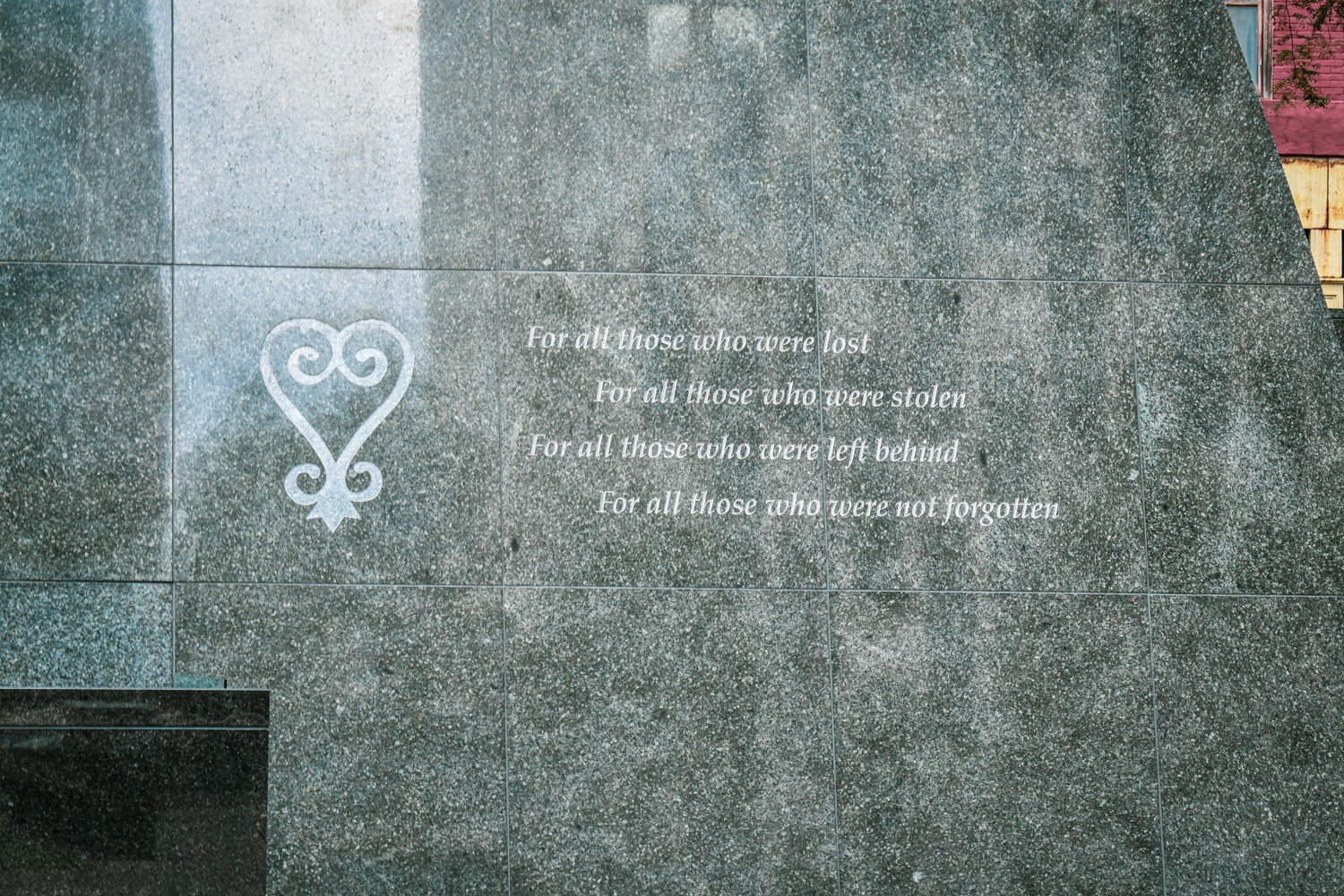

The burial ground was determined to be the largest, and among the oldest, burial grounds for enslaved and free Africans in the country. The location sat outside the city limits—while the location wasn’t too far from the land owned by some Africans in the mid-17th Century, enslaved and free Africans in the colony struggled to maintain their burial rituals and traditions from their diverse home cultures. As a burial ground during colonial rule, the people buried here carried a vast range of cultural backgrounds in West and Central African empires and states, as well as connections through enslavement to the islands in the Caribbean. While the funerals that took place at the burial ground were not documented, researchers and archeologists working on this site unearthed hints of West African burial traditions. One casket was even marked with what some scholars think to be a variation of Sankofa symbol, an idea from the Akan people of Ghana that translates to “go back and get it,” to look to the past to learn for the future.

As a result of tireless advocacy and the work of hundreds, the National Parks Service designated the African Burial Ground as a National Historic Landmark in 1993. In 2006, the site was dedicated as a National Monument. Today, the African Burial Ground National Monument stands as a spiritual site of remembrance and an active space for learning about and celebrating the impact of the African diaspora, past and present, on New York and the world.