Nineteenth-century America had a spitting problem. Public spitting, or “expectorating” as the more genteel would call the habit, was a deeply engrained aspect of male culture. The use of chewing tobacco was nearly universal among the working class, while pipe tobacco and cigars became a status symbol for wealthier Americans. It was also commonly accepted that people suffering from tuberculosis or other respiratory ailments needed to relieve themselves of pulmonary distress by expectorating freely, whenever and wherever possible.

European visitors to the country in the 1800s frequently expressed their shock and disgust at the ubiquitous spitting habit. They wrote that the sidewalks, streets, parks, factory floors, and street cars of American cities were “awash with tobacco tinctured saliva.” One investigation in Baltimore found that a single city block could collect between 2000 and 4000 individual deposits of spit in a single week. Women in particular were affected by this habit, as any trip outside the home meant collecting spit and phlegm along the hems of their floor length dresses.

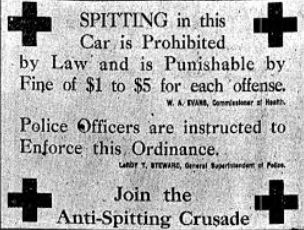

Public expectoration had long been considered a problem by advocates of the Sanitary Movement. With the 1882 identification of the tuberculosis bacterium and the understanding that the disease was spread through respiratory droplets, medical professionals began to view spitting as a grave threat to public health.