This exceptional example of LGBTQ+ placemaking on the Lower East Side speaks to a rich but oft-unspoken part of the neighborhood’s history. At the Tenement Museum, we examine how newcomers created spaces for themselves and their communities. While the lives and contributions of marginalized people go largely unacknowledged in mainstream history, there is no denying their importance in being a fundamental part of history. This is equally true when it comes to exploring LGBTQ+ narratives.

This exploration often requires reading between the lines of bias that silenced these stories. Nesbitt’s surprised note regarding the impression of “good” backgrounds, and imagining oneself among “respectable people” speaks to the lens through which the Lower East Side was viewed by outsiders.

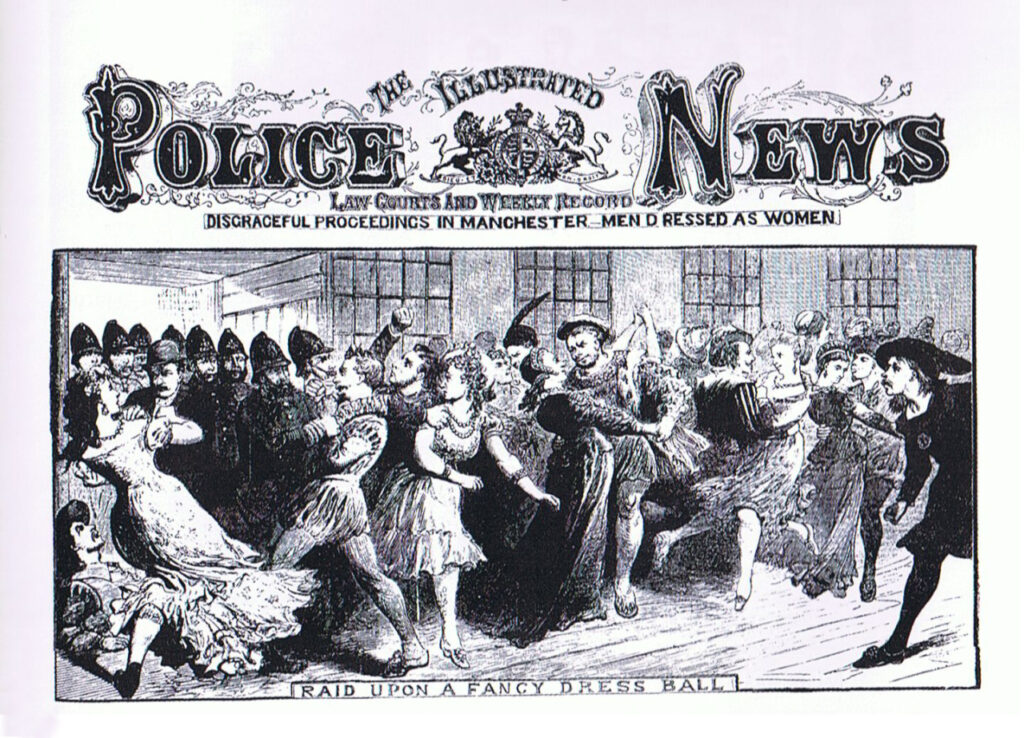

The moral panic of the 19th into the 20th centuries was linked to a middle-class imagination of the lawlessness and immorality of the LES. Middle-class New Yorkers held contempt towards immigrants settling in the neighborhood, as well as towards ideas and practices that challenged heteronormativity, such as sex work, homosexuality, and gender nonconformance. In 1849, novelist George Thompson offered an example of these perceived threats to the native born heteronormative way of life in his book, City Crimes; Or, Life in New York and Boston:

“We are about to record a startling fact—in New York, there are boys who prostitute themselves from motives of gain; and they are liberally patronized by the tribe of genteel foreign vagabonds who infest the city.” 3

Anti-vice squads pointed to the local saloons, dance halls and theaters as centers for crime and ‘degeneracy.’

However, to hold a masquerade ball at Walhalla Hall, one needed to obtain a license from the city. That the dance Charles Nesbitt attended in 1890 even took place speaks to the network of support that existed in the neighborhood for LGBTQ+ individuals. While the organized event at Walhalla Hall highlights an attempt made by those individuals to legitimize these spaces in the eyes of the city (as well try to discourage police harassment—often unsuccessfully), there were many instances of community centers being carved out in more informal–but just as vital–ways.

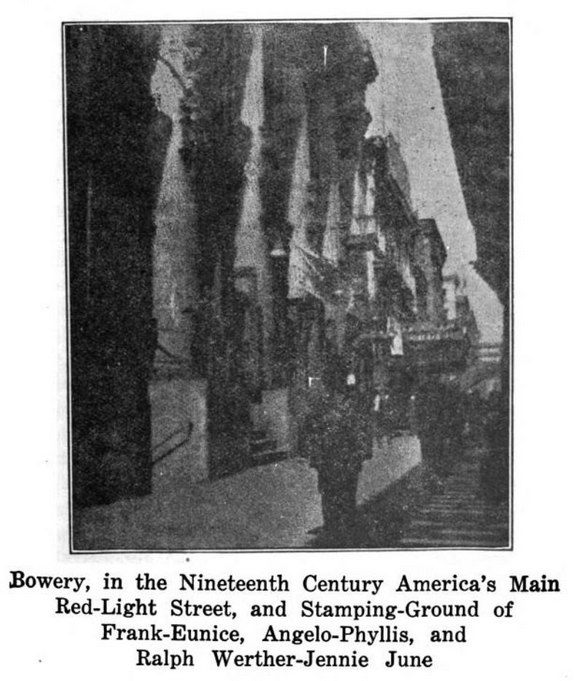

In the late 19th century, the LES was home to a developing queer subculture. Its geography featured heavily in the memories of Earl Lind (also going by “Ralph Werther” and “Jennie June”), who wrote The Autobiography of an Androgyne. Printed in 1918, this book was one of the earliest memoirs published by a transgender person in the United States.

Earl Lind’s, The Female-Impersonators: A Sequel to the AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF AN ANDROGYNE. The Medico-Legal Journal, New York, 1922.