Garnet, along with other Black ministers, began immediate outreach efforts after the riots, organizing the collection and distribution of donated supplies and money and making over 3000 house visits.

Garnet came to serve as a voice for the Black community to white New Yorkers struggling to understand the riots. Garnet’s letter to the Merchant’s Committee, signed by eight other prominent members of New York’s Black clergy, was widely circulated in both the black and white presses.5 In addition to thanking the committee for their aid and support, the letter reminds a white audience, who were sympathetic to Black riot victims that such concern was late coming, and provides recommendations on how to continue to support the Black community going forward:

“If in your temporary labors of Christian philanthropy, you have been induced to look forward to our future destiny in this our native land, and to ask what is the best thing we can do for the colored people? This is our answer. Protect us in our endeavors to obtain an honest living. Suffer no one to hinder us in any department of well directed industry, give us a fair and open field and lets us work out our own destiny, and we ask no more…” 6

Garnet’s own analysis of the riots, along with accounts from other Black clergy, differ markedly from prevailing ideas of the riots as a spontaneous act of violence by Irish mobs. While Garnet and others agree that Irish immigrants participated in the riots, they would point to instances of aid and support provided by Irish neighbors and organizations during and after the riots. The Black presses would instead lay most of the blame on anti-war Democratic politicians and the city’s numerous pro-confederate and pro-slavery newspapers for deliberately inciting violence.7 Other contributors, such as reverend James WC Pennington, wrote that in many Black neighborhoods, warnings of increasing tension, insults, and threats from white neighbors went unheeded by authorities:

“…for more than a year the riot spirit had been culminating before it burst forth. The police authorities were frequently applied to, by respectable colored persons without being able to obtain and redress when assaulted and abused in the streets. We have sometimes pointed to the aggressors but no arrests have been made.”8

Citing the lack of police action, as well as incidents of successful self-defense efforts during the riots, calls to arm and organize to prevent future violence became frequent refrains in the Black press. Similarly, community leaders used the riots to renew demands for New York’s governor to allow Black men to enlist in the state’s military units. As Black men were not yet citizens, their eligibility for service was left up to the states. Mounting political pressure eventually forced Governor Horatio Seymour to signal his approval. In November, the Union League Club successfully recruited, equipped, and funded the creation of three colored regiments, celebrating their muster into service with a parade down many of the same streets that had seen the worst of the rioting.9

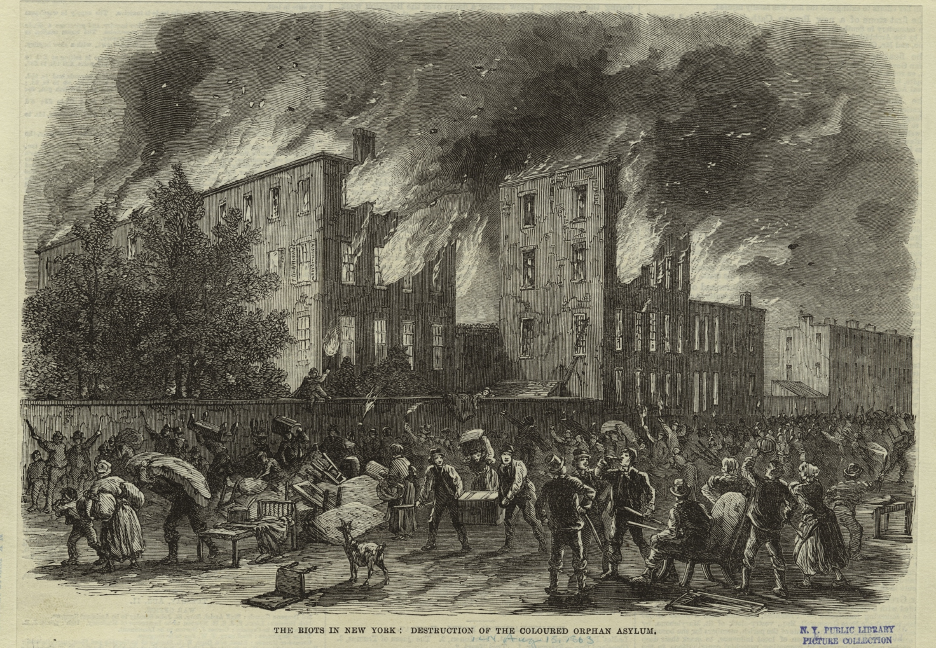

Throughout August of 1863 and beyond, greatly attended memorials for victims of the riots were held in the repaired Black churches of lower Manhattan. Funds were raised for the reconstruction of the Colored Orphan Asylum and other sites lost to mob violence. Black community leaders, like Henry Highland Garnet, continued to strengthen public alliances that emerged in the wake of the riots while parlaying raising influence into further guarantees of rights and protections for Black New Yorkers.

Despite repeated calls to return home in the Black presses, however, many refugees of the Draft Riots could not or would not attempt to make a home in Manhattan again. Albro Lyons refused to return to New York, and resettled his family in Providence. The exodus of Black families out of Manhattan continued throughout the rest of 1863, as landlords and employers, fearful of future riots, refused to rent to or hire Black applicants. By 1864, the black population of New York fell to its lowest level since 1820.10

The Black press and community groups worked together to find resources to help their communities rebuild and speak out about the violence they faced. However, the series of events in mid-July 1863 continue to be remembered as the Draft Riots, a moment where working class New Yorkers fought against an unfair conscription system. In examining the Draft Riots, it is important that we ask, why the individuals and communities victimized by the event are not central to our memory of it?