Blog Archive

An Updated History of the Undocumented Immigrant

by Lewis Hine

Immigration is very much on everyone’s mind this week with the announcement of the Trump Administration’s decision to end President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) executive order. It’s a decision that puts the future of 800,000 immigrants in jeopardy, as it affects their homes, their education, and their jobs. The threat of deportation is very real for these 800,000 young people, who have only ever known America as their home. Government policy has a longstanding history in the United States of both embracing and keeping out immigrants, of both reuniting families and tearing them apart. But an understanding of this history is the only way in which to learn from it, which is why we strive every day to tell this story.

When we talk about immigrants at the Tenement Museum, our intent is to find a common understanding of the American Dream, whether that dream was realized in 1874 or 2017. We seek to inform our visitors with the stories of everyday immigrants trying to make a life for themselves. We hope that by learning of their dreams and the trials they overcame, our visitors might come to a conclusion themselves for a question we often pose on our tours: What does it mean to be American?

by Lewis Hine

Because the families we talk about only lived at 97 Orchard from 1863 to1935, we typically reserve the legal facts to the immigration laws that might have affected them specifically. We might discuss how, before the late 1800s, the U.S. had few immigration policies. The American Immigration Council (AIC) points out that it is impossible to judge where someone’s ancestors who came here at that time did so “legally,” as there was a period when there were not many ways to immigrate here “illegally.” As the AIC notes, “most of our ancestors would not have qualified under today’s immigration laws.”

We talk about how the agents at Ellis Island, which opened in 1892, were more concerned about immigrants arriving free of disease, and that they had enough cash so as not to be a “drain on the tax dollars.” We talk about the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which is the first time the government prohibited specific ethnic groups from entering. We talk about the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which strengthened restrictions on Chinese immigrants, as well as Southern and Eastern Europeans, Japanese, Indian, and other Asian peoples.

Rosaria Baldizzi, mother of two, who entered the U.S. in the 1930s as an undocumented immigrant from Italy

We also might talk about Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor in the 1930s and 1940s, who worked on procedures to help those struggling against these tight immigration prohibitions. She would encourage undocumented immigrants to take a day-trip up to Canada, only to re-enter the United States as a legal permanent resident. We know Rosaria Baldizzi, one of the matriarchs on our Hard Times tour, likely took advantage of this loophole.

With the addition of our upcoming exhibit, Under One Roof, we are able to keep the history of American immigration moving. We’ll soon be able to discuss in context the Immigration Act of 1965. Signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, this Act (also known as the Hart-Celler Act) abolished the national-origins quota system of the Johnson-Reed Act, eliminating the discriminatory practice of denying immigration to the U.S. based on race, ancestry, or national origin. This Act resulted in a new wave of immigrants coming to our country from all over, but especially from China. One of our new families, the Wongs, were able to make it to the United States because of the Hart-Celler Act.

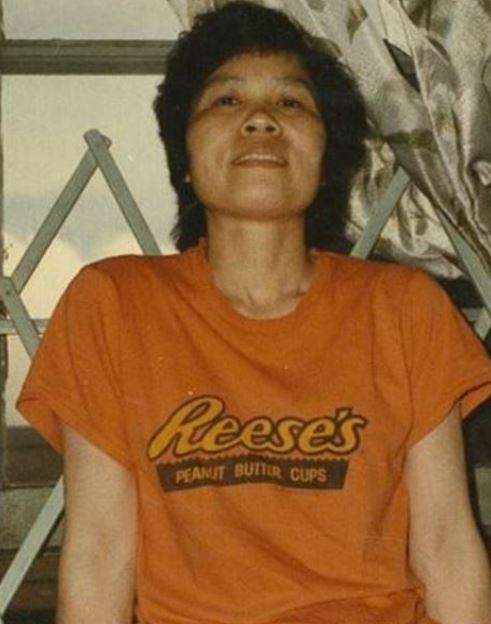

Mrs. Wong, who was able to immigrate to the United States after the passing of the Hart-Celler Act

We may even find a way to discuss the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA). This law, signed by President Ronald Reagan, sanctioned and fined employers for “knowingly” hiring undocumented immigrants. But the Act also provided amnesty to nearly 3 million undocumented immigrants. Although in hindsight, the law is not considered a success, the amnesty is provided is seen today as one of the few benefits. A former Reagan speechwriter named Peter Robinson said, “It was in Ronald Reagan’s bones — it was part of his understanding of America — that the country was fundamentally open to those who wanted to join us here.”

We could also mention the Immigration Act of the 1990s, which raised the annual cap on immigration and revised the political ideological grounds for exclusion and deportation. It also allowed people coming from countries afflicted by natural disasters or armed conflict to be granted “temporary protected status.” By the turn of the century, immigration had become heavily linked to national security. Several programs and laws were passed singling out foreign-born Muslims, Arabs, and South Asians, as well as mandated improvements and tamper-resistant documents for entry, the prevention of obtaining a driver’s license without proof of citizenship, and the building of an additional 850 miles of fences along the Mexico border.

Tenement Museum educator Raj Varma was naturalized in 2013 at a ceremony held at the Tenement Museum

By looking at the scope of our immigration history, we can see that it has moved like a pendulum, both for the benefit of and the disadvantage of immigrants. Our history is one of inclusion and exclusion. With all this knowledge, we then become better suited to answer the question: What does it mean to be an American, and who gets to make that decision for the nation? At one point does an immigrant truly become an American, the day of their naturalization ceremony or their first day of school? The day they arrived or the first day they start thinking of this country as “home”?

- Post by Gemma Solomons, Marketing & Communications Coordinator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum