Blog Archive

The Legacy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

March 1, 2016

Images of the idealized Gibson Girl created by Charles Dana Gibson. This image was published in May of 1900. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

With the boom of the ready-to-wear garment industry, American artist Charles Dana Gibson personified what he believed was the standard of American female beauty. A woman with a long neck, a pompadour hair-do, tall and slender, with curvaceous hips and bust, adorned in a shirtwaist. Shirtwaists, which were originally modeled from the men’s shirt fashion of the time, were functional, ready-to-wear, and signified an independent, American woman. Upper-class American women were often identified as the classic Gibson girl; however, women across socio-economic classes were wearing, and making shirtwaists. Many immigrant women were employed in the garment industry, working long hours for low wages, often in unsafe working conditions.

New York was the epicenter of the ready-to-wear garment industry for both men and womens’ garments. Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, both German Jewish immigrants, who became titans within the garment industry, owned the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. They operated their business out of the eighth, ninth, and tenth floor of the Asch building, now known as the Brown Building, which today is part of NYU’s campus and located right by Washington Square Park. Many of their employees were young immigrant women from Eastern and Southern Europe. In 1901, the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union was established to protect the rights of these workers. In 1909, many of these workers left their sewing machines and went on strike. Known as the “Uprising of the 20,000”, these working-class immigrant women demanded a 52-hour work week, better pay, safer working conditions, and recognition of the unions. Small shops gave into the demands of their workers, but larger shops, like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, did not. They were willing to provide “better” pay, and shorter hours, but they were not willing to recognize the union, and without the security of the ILGWU, better pay and hours would not be as protected. Thirteen months later, tragedy broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory.

An interior of the Asch Building after the fire. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

As unsuspecting workers were finishing their work day on Saturday, March 25, 1911, a cutter on the 8th floor flicked a lit cigarette into a pile of lawn, a highly flammable fabric. The fire quickly spread throughout the top three floors of the building. The first alarms were sounded at 4:45pm. Workers, who had absolutely no emergency training, were frantic as the only available safety device available were buckets of water dispersed throughout the large factory floors. Since it was the end of the workday, some of the doors were locked. Distrusting of their employees, factory managers would lock some of the exits to inspect workers’ bags to ensure there was no theft. The doors that were not locked were inward opening, and panicked workers who were desperate to escape shoved themselves against these doors, locking themselves in. Those who did not escape the fire either died in the building of asphyxiation or jumped out the windows. Since this was a Saturday, hundreds of people were nearby in Washington Square Park, and rushed over to watch the horrific scene. 146 employees, mostly young immigrant women, perished in this fire. It was the deadliest workplace tragedy in New York City until September 11, 2001.

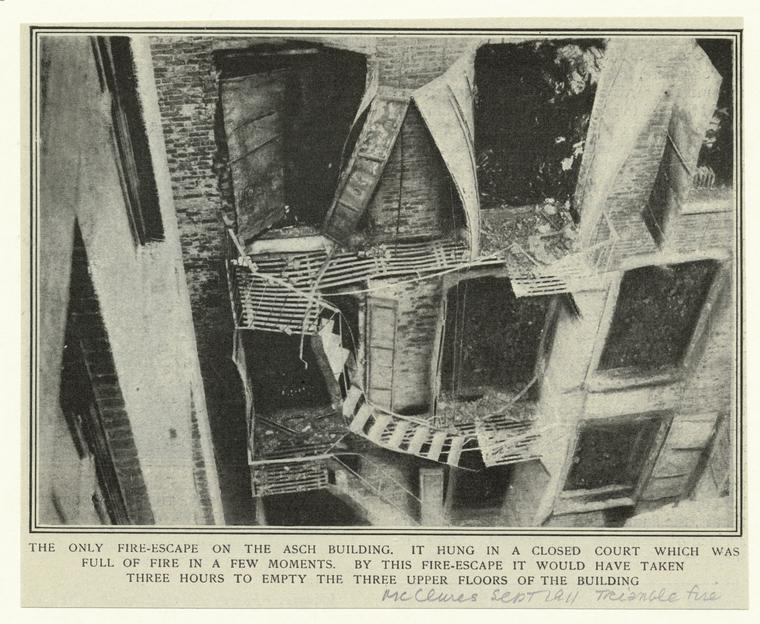

One of the fire escapes revealed to be totally inadequate after the fire. Image courtesy of the NYPL.

Harris and Blanck were indicted with first- and second- degree manslaughter but it was ruled that they could not have known the doors were locked at that exact moment. They were acquitted of the charges, but in 1913, were found liable of wrongful deaths, and had to compensate the victims’ families $75 per deceased victim. This fire resulted in legislative reform that enforced workplace safety. In fact, Frances Perkins, who became Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor, witnessed the fire, and made it her life’s mission to protect workers’ safety and end child labor.

It is important to remember tragedies like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and the victims that perish that day. Though tragedies like this one are less frequent in the United States then they once were, we cannot thank safety regulations alone. One of the reasons this kind of labor disaster has faded from the national stage is because a lot of factory production has moved overseas. In order to continue to honor the memory of the Triangle Shirtwaist victims we might turn our attention to the factories of American companies that are no longer down the block but across the ocean. In recent decades some American clothing brands have reasserted production in the United States; here too, is a chance to be an activist. Sometimes supporting safe labor begins by looking at a tag.

–Posted by Alana Rosen, Manager of Evening Events at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum