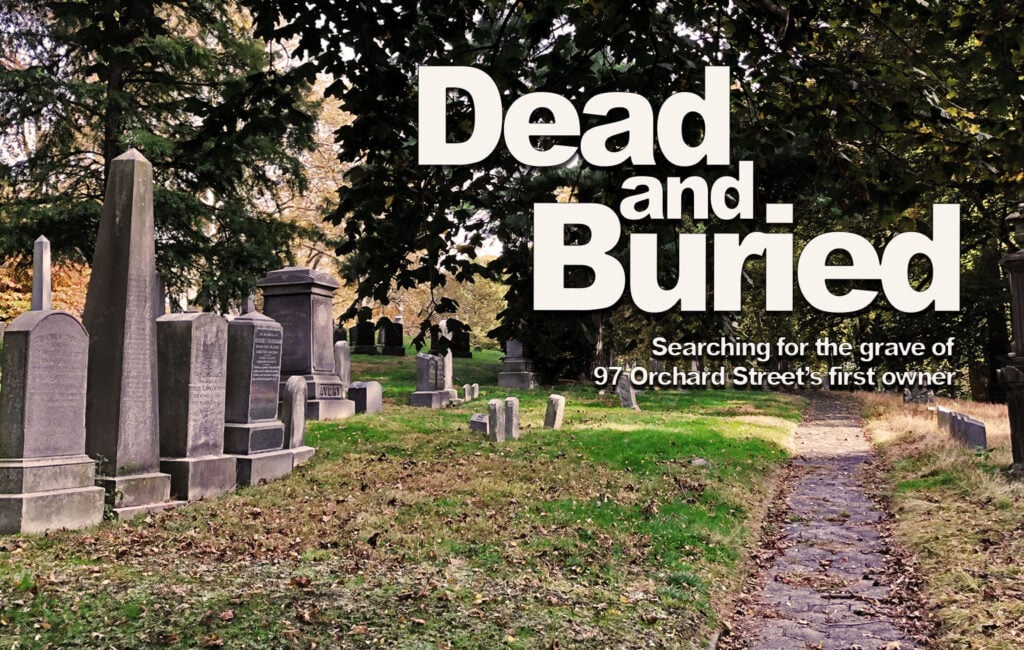

This is part two of a four-part series documenting the search for the grave of 97 Orchard Street’s first landlord, Lucas Glockner, in Green-Wood Cemetery, a 478-acre cemetery in Brooklyn that opened in 1838. Read part one here.

Great Reads

Dead and Buried Part II: The Lost

July 8, 2020

“GUY!”

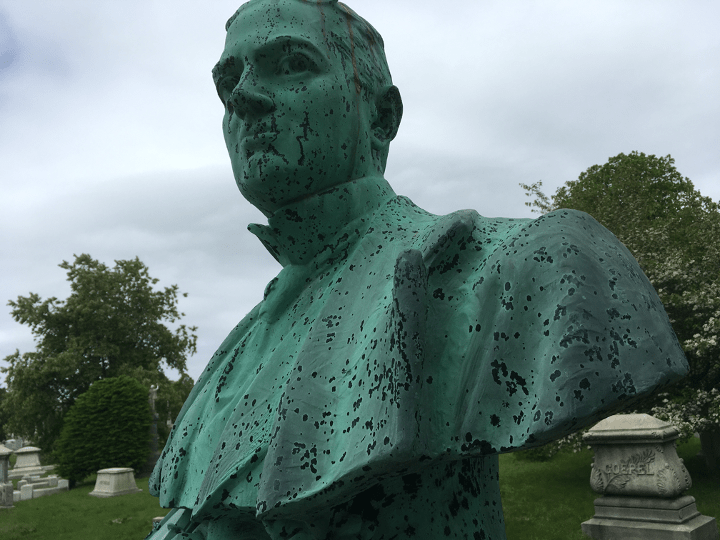

Our 21-month-old tour guide abruptly announces our next stop in Green-Wood Cemetery. We are on a hopeful search for Lucas Glockner, the landlord of 97 Orchard Street and current home of the Tenement Museum. We approach a lot named for William H. West. A bronze bust of West scans the horizon from its perch atop a polished stone wall. He is depicted hovering like a ghost over a banjo – the whole sculpture cast in bronze. This is the “GUY.”

West’s larger than life-size bust beacons people to walk up the steps for a closer look. Invariably they leave in quiet admiration unknowing that the mint green patina conceals an ugly and largely unreconciled history.

William H. West. The GUY… Who was he?

Elements of his grave offer some superficial clues. In addition to noting the span of his life, 1853- 1902, a plaque under his portrait lauds him as, “The Eminent Minstrel”- which, along with the banjo, implies that West was a singer of some kind. That’s enough for most folks and they walk away, while in the east corner of the plot a bronze comedy theater mask seems to laugh at them.

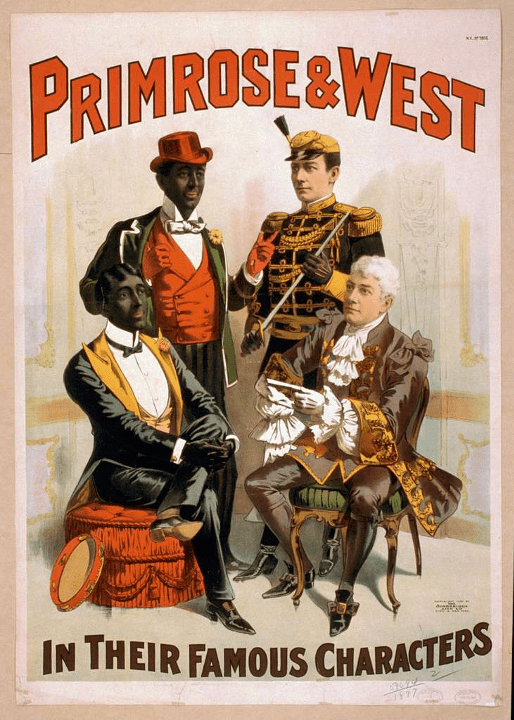

Tall, well-built and handsome with a ’remarkably sweet voice’ and described as a ’graceful dancer,’ West spent his entire career as a stage actor, according to Appleton’s Annual Cyclopedia 1903. Over a 30-year partnership with childhood friend and fellow performer, George Primrose, the two built a lucrative and wildly popular empire based on performing in blackface, a genre of comedy theater featuring racist portrayals of Black characters largely performed by non-Black actors wearing black make-up. West and Primrose – like countless others in the Victorian Era entertainment business – profiteered off of anti-Black racism. Looking up at West’s ghostly green bust, I can imagine him painting his face before a performance- running lines in an affected accent. How do I explain this GUY to my daughter?

Sensing I’m unsettled, my daughter says, “GUY” again, but it sounds more like a question.

In response, I say, “Racist actor GUY.” She nods and leads us away – the corner comedy mask won’t have the last laugh this time.

West’s minstrel performances were vastly popular in New York City and around the United States. No matter the social class, ethnic or racial origin, all walks of life attended minstrel shows. It’s entirely possible that Lucas Glockner took his family to a minstrel show. Can I imagine him laughing during a blackface routine?

What do I really know about Glockner?

His story begins in 1821 with his birth in the German State of Baden, and in some respect, it begins again in 1843 with his immigration to America. He arrived in New York City as a tailor. On May 2, 1844, Lucas married Catharina Nickel, an immigrant from Rheinbaiern. In their 18 years together Glockner’s tailoring business grew and they raised three sons, but in October of 1862, with Catharina’s death, their journey ended.

I look over at my partner, who is being pulled by the finger to a dandelion patch, and I wonder what Lucas was going through after Catharina died. No official primary source helps connect me to Lucas’ loss. Catharina’s death might have inspired a life change, because four months later, on the 26th of February, 1863, he joined Adam Stumm and Jacob Walter in the purchase of the lot previously owned by the Second Reformed Presbyterian Church on Orchard Street. With this purchase, these three tailors ventured beyond the needle trades into the emerging field of New York City real estate. The lot was evenly divided and, on each section, these partners constructed their own five story tenement house.

By 1864, Glockner’s tenement at 97 Orchard Street was open to residents – the majority of them being recent immigrants from the German States. He moved into one of the apartments and remarried. Together with his second wife, Wilhelmina, they raised another four children. Though the 1868 City Directory indicates that Glockner moved to Allen Street, he remained closely tied to 97 Orchard Street until September 1, 1886 when he sold the building to William Morris. The neighborhood was changing with newcomers arriving from Russia and Austria; and Glockner was growing old. Perhaps it was time to move on. But I can’t help but wonder, as we walk through tall grass crowding over old stones, how did he see 97 Orchard Streetafter he sold it? What memories did the building inspire? Maybe he turned over the keys and never looked back…

My ideas about Lucas Glockner become fuzzier the more questions I ask. I’m hoping that finding his grave will offer some kind of resolution.

But for that, we have to wait until tomorrow, Monday, when the office is open.

Continued in Dead and Buried Part III: The Found…

Image Credit: Primrose and West Poster: Created and copyright 1897 by The Strobridge Lith Co, Cin’ti & New York. Minstrel poster collection (Library of Congress)