Blog Archive

Don’t Doubt the Immigrant: Frank Capra and the Love of the Adopted Nation

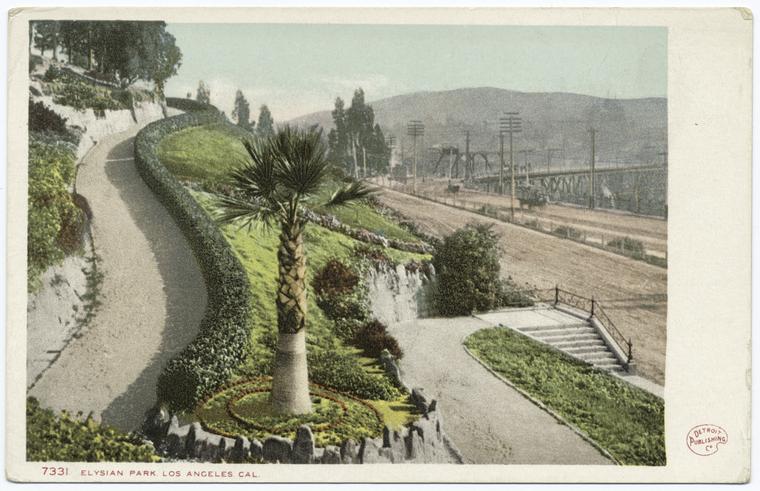

Elysian Park, Los Angeles: where fantasy and reality jockey for followers. This postcard was created in 1904, around the time when the Capra's moved to L.A. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

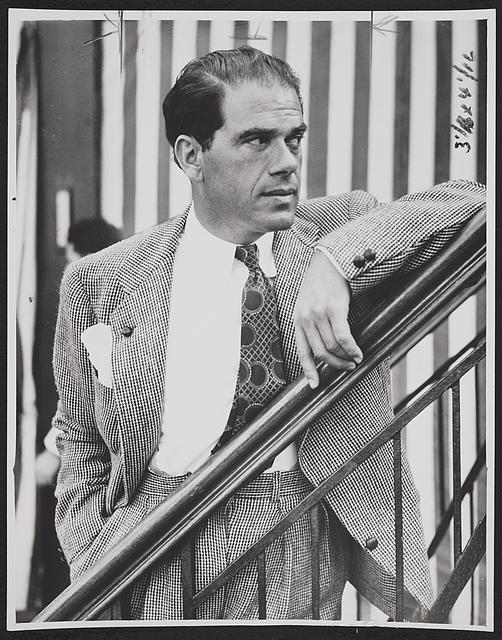

A friend of mine from back East moved, for college, to the west coast. Stalled in miles long traffic on a L.A. freeway she stepped out of the car along with the drivers in front of her, looked at the sun setting into the smog-swathed LA basin, sighed, and said “Converts are the worst.” What she meant was that faced with the all the horrors of freeway traffic, she still felt nothing but affection for her newfound home.

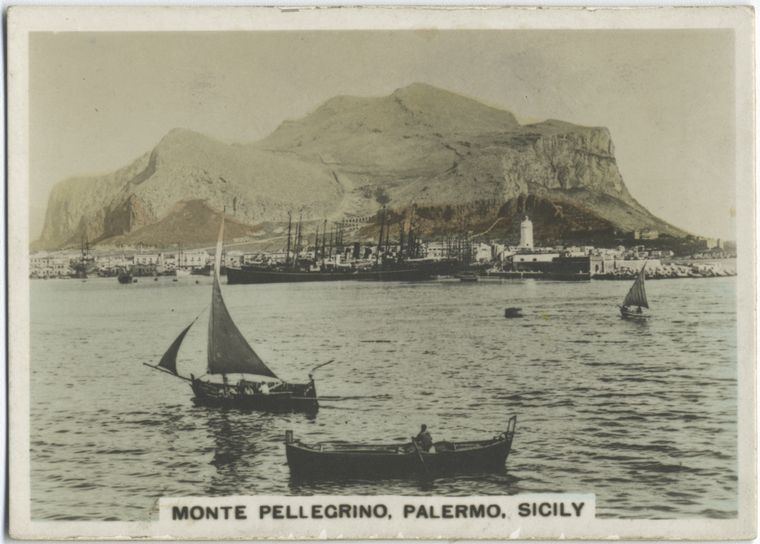

Sometimes, especially for immigrants, an acquired home can be beloved in the way natives could never imagine. During the course of his forty year career, Frank Capra directed some of the most iconic American films of all time that include It’s A Wonderful Life, It Happened One Night, and Mr. Smith Goes To Washington. It may come as quite a surprise that Frank Capra, a director known for some of the most classic “American” movies of all time, was born in Palermo, Sicily. Not only did Capra make beloved movies about the American dream, but he was also a devoted director of war propaganda for the United States War Department during World War II. Now that is patriotism.

Looks beautiul from a distance. An image of Palermo, Sicily: a city of intense beauty and a history of crippling poverty. Image courtesy of the NYPL.

Frank Capra was born on May 18, 1897 in Palermo Sicily to illiterate parents. When he was six, he travelled with his family to the United States, settling in Los Angeles. Like so many other Sicilian immigrants in 1903, the Capras travelled steerage, the cheapest possible class.More than merely survive, Capra was inspired to rise above poverty from an early age. He worked from elementary school onward, beginning as a newspaper boy. Reportedly, he was competitive and struggled with the other newsboys for the best possible spot from which to sell papers. Hardworking, Capra won a scholarship at the California Institute of Technology while still working several jobs. After graduation in 1918, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and taught mathematics, a role he would later revisit in an unexpected way.

After leaving the army, Capra was unmoored for a time until he convinced someone in San Francisco he had directorial experience. He had none. The short film, however, got him hooked. He worked his way carefully back up the production ladder, learning from the bottom first as a prop man, a film cutter, an assistant director, a title-frame writer, and then a gag writer. Eventually Capra came to work for Columbia Pictures, which was at the time a lesser studio. Thanks in no small part to Capra’s string of hits; Columbia soon became a leading studio.

Part of what made, and makes, Capra’s movies such a success is their depiction of the America Americans wanted to believe in. Many of the main characters are optimistic and idealistic almost to a fault. Strong individuals often exercise their rights for the sake of those less fortunate than themselves. Some of his films, like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, simultaneously mock and critique corruption in U.S. politics and dare Americans to do better by their democratic system.

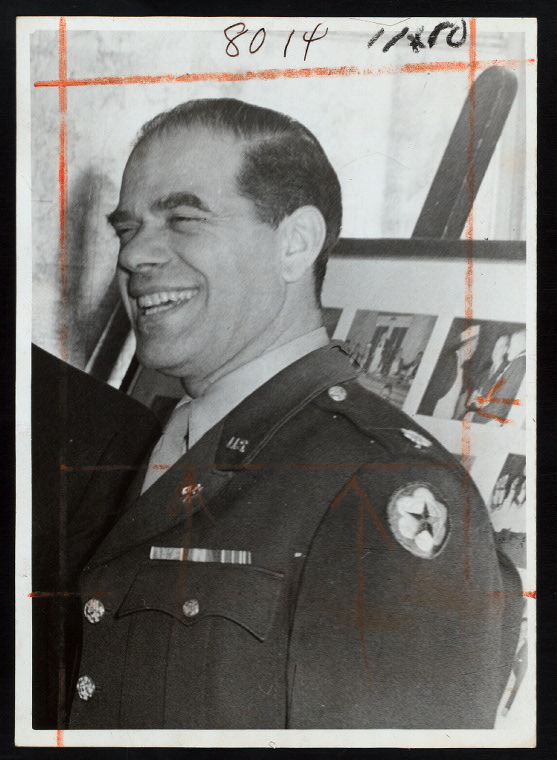

Frank Capra in uniform again, this time supporting the War Department in their propaganda efforts for WWII. Photo courtesy of the NYPL.

When Capra first saw Leni Rienfenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film, The Triumph of the Will, at the Museum of Modern Art in the spring of 1942, he was horrified. The film was so powerful and so captured the myth of German Nazism that Capra remembers thinking, “We’re dead. We’re gone. We can’t win this war.”

Fortunately, Capra fought the only way he knew how. He joined the War Department and in collaboration with several prominent directors, including John Huston, John Ford, began to direct and develop War Propaganda. He quit his Hollywood job to commit solely to this project. The result was the arresting seven-part series, “Why We Fight.”

Capra’s story is hardly unique; the Baldizzis, who lived at 97 Orchard Street, were also born in Palermo and became devoted to FDR can but it is a highly visible example of how a person who is born in another country and into another culture can become devoted the one in which she grows up. The optimism and idealism in Capra’s films did not always coincide with the realities of American life. When the Great Depression turn into the Second World War and Americans were less moved by Capra’s perpetual happy endings Capra stood by his ideology. It was no marketing gag, he really believed in the power of the American Dream, and why not? For Capra it was a dream come true.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator