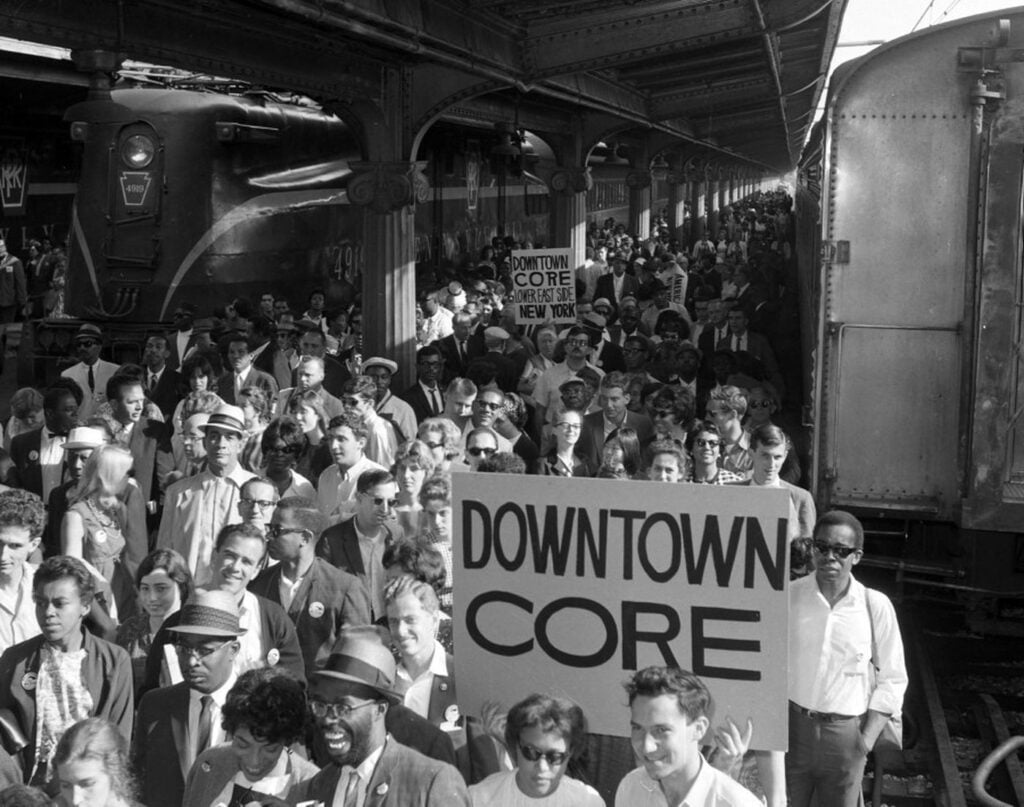

When they returned, this interracial group of young New Yorkers, mostly Black and Jewish college students, would have gone back to their day-to-day activism. From their headquarters on Delancey Street, they planned direct action to solve issues of injustice on the Lower East Side.

This branch of CORE, like all branches, was established to focus on local concerns while connecting to national initiatives. Downtown CORE volunteers identified housing as the major concern for Black and Puerto Rican Lower East Siders, and put their energy into documenting illegal racist practices by real estate agents and reporting them to the city, protesting against poor tenement conditions at the Department of Buildings headquarters, and conducting surveys with neighbors to determine what people needed. They also joined forces with other CORE branches, launching sit-ins at construction sites to demand more construction jobs for Black and Puerto Rican New Yorkers.

As civil rights workers found across the country, their work wasn’t welcomed by everyone in the area: during a demonstration in the summer of 1964, a group of Downtown CORE volunteers were physically assaulted by white residents in Little Italy. And the volunteers would have had similar conversations as the ones happening across the civil rights movement: how do we respond to attacks and disagreements? How do we support each other? How do we move forward?

There undoubtedly would have been debate, challenges to their hope, and hours and hours of their time dedicated to discussion and negotiation. What they might have heard and discussed at the March on Washington, about the need for better jobs and economic security for Black Americans, about the need to act now and resist more gradual or moderate solutions, might have stuck with them.

These questions and issues are ours to navigate now, and we look to the history both of leaders like Dr. King and everyday volunteers from Downtown CORE as we consider what’s needed in the continued work of justice.