Blog Archive

Emma Goldman: The Firebrand Still Glowing in 2015

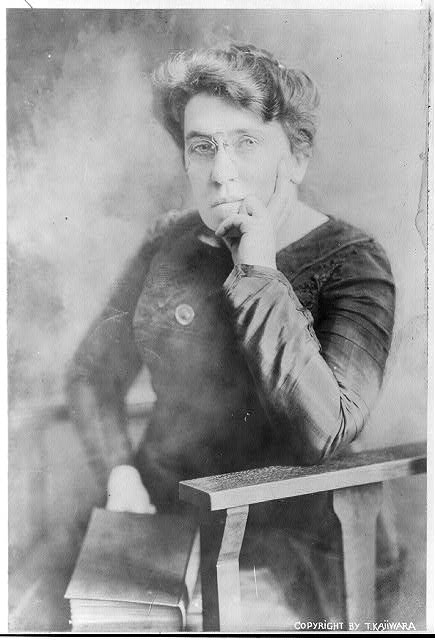

Always going somewhere, this photography for the Library of Congress archives shows Goldman on a street car in 1917. Photo courtesy of the LOC.

Unlikely, though it may seem, one of the figures to have the most lasting impact on American labor rights is a Lithuanian born, Russian educated, anarchist named Emma Goldman. A towering and unique figure in the early activism for workers’ rights, Goldman was a charismatic speaker and a prolific writer who championed issues that are still disputed today. When University of California, Berkeley informed the editor of the Emma Goldman Archives, housed there, that after 34 years and $1.2 million in support, funding had run out for her project Prof. Falk’s reaction would have made Goldman proud.

Emma Goldman’s reputation is built on her skepticism of authority and her championship of free speech. Therefore it was no surprise that the editor and director of the archives, Prof. Candace Falk, did not immediately take the University’s statement at face value. “I think there’s a fear of a woman anarchist immigrant.” Said Falk in an interview with JWeekly.

But let us take a step back. Who is this woman who remains so controversial fifty years after her death? Goldman was born in Lithuania to a Russian Jewish family of shop keepers. She was educated in Eastern Prussian and in Russia’s St. Petersburg. While she was at school Czar Alexander II was assassinated and the swell of revolutionary ideologies overflowed in Russia.

Goldman moved to the United States with her family in 1885 and brought the spirit of revolution with her. After a brief, unhappy marriage to a fellow worker in a Rochester mill, she shrugged off her old life, boarded a train, and found comrades, love and calling on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. After quickly joining Johann Most in the publication of his Anarchist newspaper, and adopting some of Most’s expert oratorical skill, Goldman’s star began to rise.

In 1889, she met Alexander Berkman, a fellow anarchist and perhaps the great love of her life. Berkman took his political beliefs to the point of violence which Goldman never did. In 1892, Berkman was imprisoned for his assassination attempt of Henry Clay Frick whose treatment of workers on strike Goldman believed to be reprehensible. Frick worked tirelessly to make Andrew Carnegie’s steel mill profitable and in 1892 this included sharp wage cuts, eviction of workers from company housing and refusal to negotiate with labor unions. Frick famously made use of the Pinkertons, a hired police force, to break the subsequent strike with a battle that left dead on both sides. While Berkman was in prison however Goldman only continued to gain following and respect for her advocation of labor rights and free speech.

Goldman’s life from 1892 till her death in 1940 is peppered with arrests. Her activist anarchist newspaper, Mother Earth, was banned from circulation through the U.S. Postal Service and then entirely. She was arrested for speaking about birth control, homosexuality, for gathering crowds, protesting World War I and for criticizing the police.

Most significantly Goldman was never afraid admit she had fallen victim to idealism. When a forced deportation brought her back to communist Russia she was crushed by disappointment in the reality of communism. She soon published a manuscript about My Disillusionment with Russia. Goldman left Russia and through the marriage of an old friend Goldman gained British citizenship. Her friends and supporters from every strata of society sustained her after her deportation helping her to continue to write and publish her memoirs through Knopf. She did however protest the price of the memoir, which, as a true anarchist, she found excessive during the Great Depression. As early as 1934 she identified Hitler and Mussolini as Traders in Death and was outspoken until her death in 1940.

So what will happen to the archive of this remarkable and controversial figure?

Archive direct Professor Falk pointed to the Mark Twain archive which continues to be generously funded by the University as an example of biased financial support. When asked about this theory the Victor Fischer, associate editor of the Mark Twain Papers and Project, said about possible reasons for the discrepancy in support “The obvious one is that Emma Goldman is a Russian Jewish anarchist and her politics don’t necessarily meet with everybody’s politics. I can’t say for sure that’s why, but for some reason, Mark Twain is a figure who has been embraced by everybody no matter what their politics.”

Goldman wrote constantly throughout her life: letters, magazines and manuscripts. Photo courtesy of the LOC.

Is the funding cut attributable to a chronic lack of research funding or a deeper ideological issue? For the moment, the Emma Goldman Papers and Project remain at Berkeley but their future is uncertain.

Posted by –Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator

–with a great debt to the research of the Public Broadcasting Service for the Emma Goldman segment of the American Experience program. Which research, in turn, was done in part through the Emma Goldman Papers Project, housed for now, at University of California, Berkeley.