Blog Archive

Factory Girls: Fashioning a New Identity

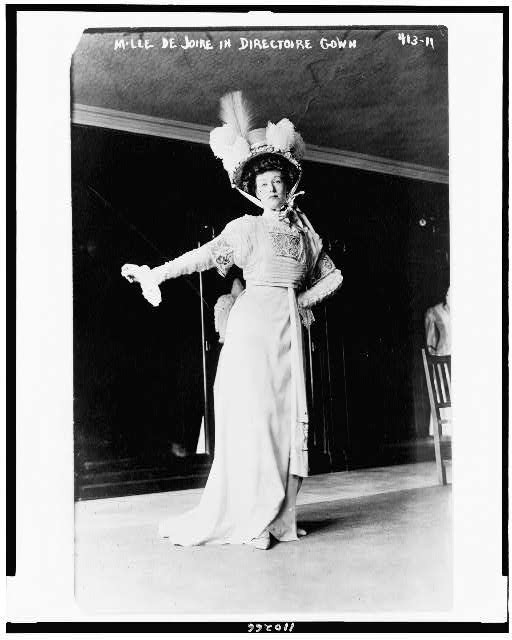

The picture of high fashion. This image from around 1907 shows the kind of luxurious attire to which working women aspired. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Real lovers of fashion have never doubted its importance. But you might ask where was the place for fashion in the tenements of the Lower East Side? Other than stitching and pinning the fashionable garments of the wealthy, were women in the early garment industry really able to indulge themselves in the latest trends? The answer is a resounding yes!

The same generation of young women who saved their pennies for dime novel romances also scraped together small amounts of money on their attire. Much like spending your savings in a romance novel, purchasing fine fashions at first seems like an unwise investment. Actually, for these young immigrants and second-generation factory workers, clothing helped them to tell important stories about themselves.

For the factory workers wearing, the styles they worked on in the factories was important order to feel independent from the repetitive labor. Photo courtesy of the New York Public Library.

For these young factory workers, clothing told tales of success, both financial and cultural. With a few cents the girls could buy new trim for a dress or new ornaments for an old hat. As the fashion at the time among the wealthiest Fifth Avenue ladies was for towering hats, working-class women often just continued to pile additional ornaments on a hat they already owned. Voila: Fashion and thrift! Working-class woman often favored fashions that broadcasted their femininity. At that time working in factories, or working at all, was not considered at the time to be very ladylike. (Female factory workers would continue to carry masculine stigma for nearly 40 more years. Extensive government campaigns, including the famous Rosie the Riveter, were necessary to coax the much-needed feminine workforce into munitions factories during World War II. Shortly thereafter, the returning male workforce pressured them back into the home in the 1950s.)

Lillian Wald was a reformer and advocate for working-class women in the early Twentieth Century. However she also held opinions about their dress.

Therefore, these earlier factory workers were some of the first American woman to embrace – along with towering hats – the “French” high-heel. Three inch heels were not the only daring fashion move made by these young women. They also had quite an appetite for color, when most of the fashion called for muted tones. Lillian Wald, a well-known activist working among the tenement populations at the Henry Street Settlement House, supposedly offered to buy a woman’s shirt from her for $5 because the bright color offended her so greatly! Lillian Wald is also said to have been aghast at how intently these women desired silk petticoats. The petticoats would have been expensive and invisible. However the silk would have made a subtle, dignified rustle heard by the wearer and those in close vicinity. To the wearer of the petticoats, the sound would made her feel like a real lady.

The fashions worn by the working-classes were a much closer match to that of the truly affluent women in New York than to the middle classes, but in many ways were free from the standards of either group. These working-class women were probably glad to establish their own expectations after the swarm of opinions they encountered from all sides. Their mothers may have had old-world expectations for dress and behavior, while many Americans probably viewed them dirty and unrefined. They also would have received advice from well-meaning reformers with strong opinions such as Lillian Wald.

Factory workers supposedly conjured aristocratic surnames for themselves inspired by the characters in their dime novels. It is no surprise then that they conjured attire for themselves that matched their own dreams of American womanhood.

Working women in 1907 outside of the Dix building displaying their careful attention to fashion. Photo courtesy of the New York Public Library.

– Posted by Julia Berick