The Tenement Museum’s Jason Eisner and his daughter return to Green-Wood Cemetery, and in the process of aiding a few people in their search for the grave of artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, uncover a haunting moment in Lower East Side history. A story told in three parts and two paintings. Read part I now.

Great Reads, New York City History

Haunted by History Part II: Restless Spirits

October 21, 2020

“C’mon. Let’s find the Artist Guy,” I said.

And with that my daughter starts her walking tour to find Basquiat. She has been leading us on walking tours through Green-Wood Cemetery since the COVID crisis hit the city. Trailing behind us are two Basquiat fans, relieved to have a tour guide who knows the way (even if she is only two years old.) I have sympathy for this couple, lost on their pilgrimage. Basquiat’s grave is oddly illusive.

It’s not so much that it’s off the beaten path. Quite the contrary, Basquiat is buried along an old walkway through Green-Wood. At a glance the grave markers along this path appear identical. These conforming stones defy all expectations of a suitable grave for a mythical trickster art star. A final trick, perhaps?

As we go, our footsteps fall over dried leaves and tall grass. My daughter navigates this terrain with assertive steps- her foot forcefully landing on a fragment of an American flag cut apart by weary landscapers. Somehow this gets me thinking about mythical narratives again.

Basquiat built his career as an artist of the New York Downtown scene. He is associated with the East Village and the Lower East Side, which, from the late 1970’s through the 1980’s, was popularly considered a raw and dangerous place- the downtown rival of the Bronx uptown. In the context of the larger American mythology, these neighborhoods epitomize urban decay and speak to a deeply rooted fear of cities.

For people without connections to the Lower East Side, the mythical narrative of drugs, crime, sex-trafficking, arson, gangs; and artists drawn to visions of ‘authenticity’ (not to mention cheap rents) continues to haunt the neighborhood. This myth eclipses the myriad grassroots community movements unfolding at the same time. Moreover, it dehumanizes the people of the Lower East Side who worked, rose families, went to school, shopped for groceries, danced at tenement house parties, drank black coffee, prayed for salvation, went to parks and movies; who searched for jobs and apartments and love and escape, or simply a way to get by.

Criminality dominates the narrative, but oddly enough, the myth excludes policing and the systems of inequality which made parts of the city more vulnerable (and by extension, more desperate). Those narratives restlessly stir under popular images of graffiti-layered subway trains, ruined buildings, and people living on the edge. A cemetery being a place of remembrance, it should come as no surprise that Michael Stewart’s name suddenly enters my mind.

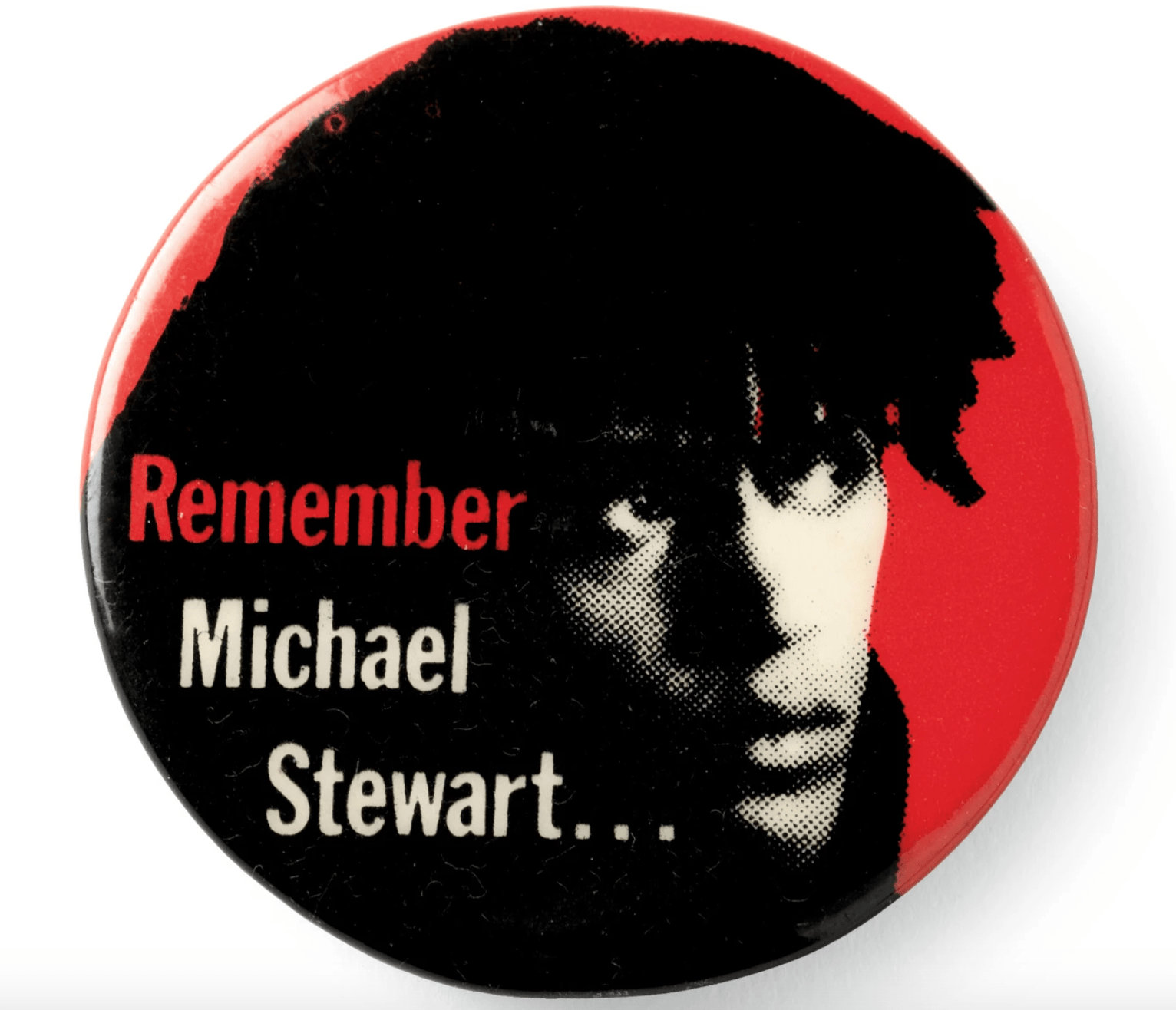

Michael Stewart was a Black artist and model who, on September 15, 1983, was taken into police custody for allegedly writing graffiti on the walls of the First Avenue subway station. An hour later, he was delivered to Bellevue Hospital, hogtied and in a coma. Thirteen days passed before Michael Stewart slipped away forever. He was 25 years old.

The officers involved in the arrest, John Kostick, Henry Boerner, and Anthony Piscola, claimed that Michael had suffered a series of wounds in an attempt to evade arrest, but medical examiners cited a combination of damaging blows to the spine and asphyxia resulting from force applied to the neck as the primary cause of death. Eye witnesses testified they’d seen Michael being beaten and claimed they heard him shouting, “Somebody help me, somebody help me!” Were these his final words?

This high-profile act of violence by three white members the New York City Police Department happened on the northern edge of the Lower East Side. Cries rose up against police brutality and anti-Black racism. Artists and activists aided in mobilizing demonstrations and calls for justice.

Michael Stewart. 1983. How did I forget?

His name resurfaces from memory as the number Black people killed in police custody continue to pile up- the haunting echo of a violent anti-Black racist legacy. How can I keep their names from slipping away?

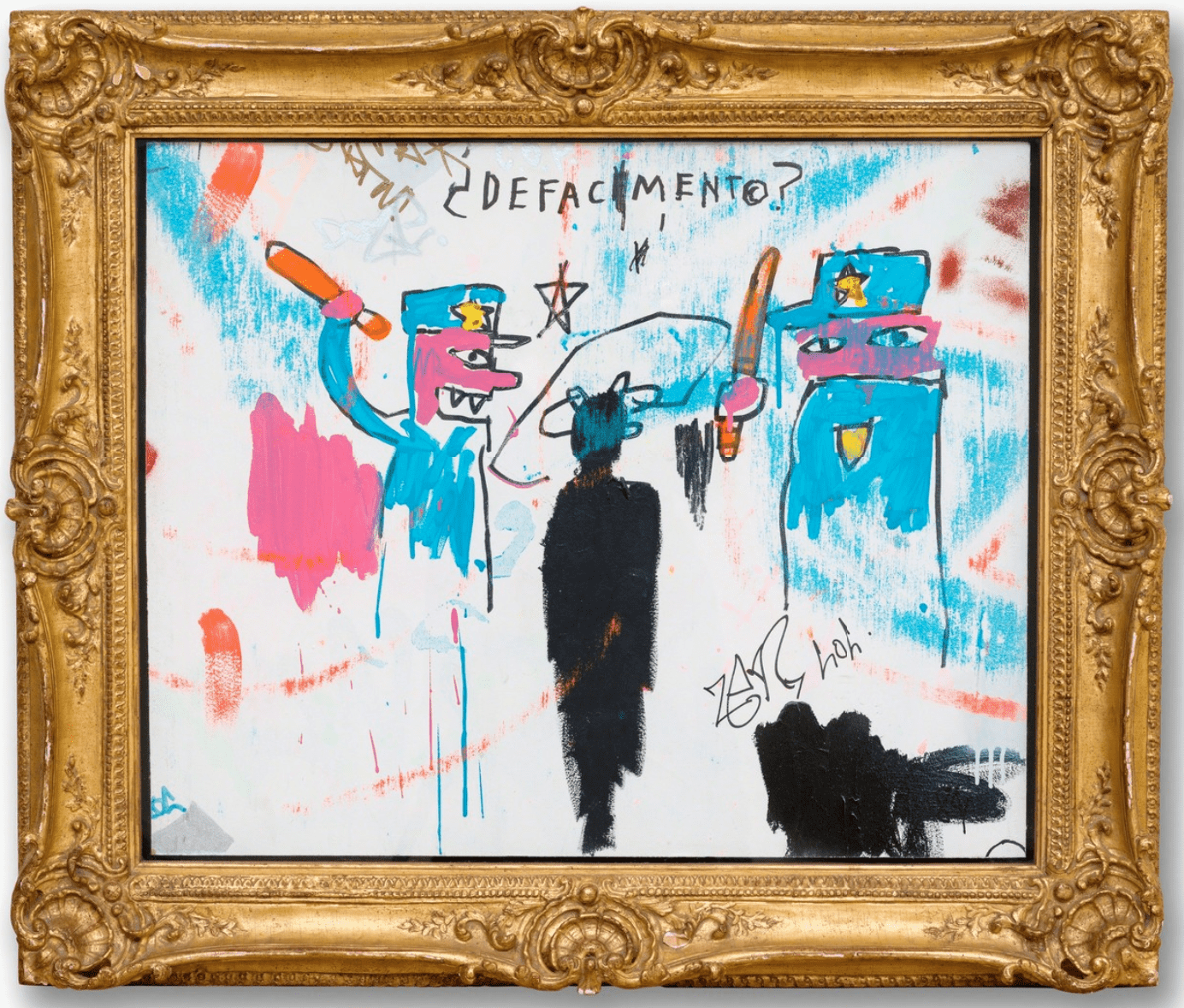

A solid black shape divides the image along the vertical axis. The shape resembles a figure. This figure is flanked by two cartoonish police officers. Their pink faces are set with penetrating eyes. One’s mouth is open bearing the fangs of a snake- their orange clubs raised high, about to fall. Looping black lines circle the figure symbolizing dizziness- the result of repeated blows to the head. A third police officer is disembodied, floating free of Basquiat’s hard lines. The star of his hat flies above the dark shape- taunting it. The pink of his face pushes one of the officers forward, his blue uniform thrashes about the image in dry violent marks, and the orange of his club is painted as a series of gestures darting across the image, cutting over the dark shape at the neck and back. A second black shape, suggestive of a head, quietly anchors the bottom right corner. Does the body of this head belong to us, the viewers? Are we the witness?

There is an urgency and a necessity to this image, yet Basquiat never intended it for exhibition. Painted directly on Haring’s studio wall, the rawness of the image reflects Basquiat’s struggle to process the event. The curator Chaédria LaBouvier, whose extensive research of “The Death of Michael Stewart,” led to a 2019 exhibition at the Guggenheim (the first ever by a Black woman), asserted that Basquiat had a kind of faith in Keith Haring. And in the safety of his trusted friend’s studio- without the self-conscious pressures of the art world- Basquiat freely meditated on the condition of violence haunting Black men in the United States. “It could have been me. It could have been me,” he said, reflecting over Michael Stewart’s assault and death as well as his own vulnerability. I can’t help but wonder if the head-like mass peering into the image is a representation of Basquiat himself.

My daughter asks to be carried on my shoulders and waves as we walk away, but it can’t escape the feeling that something is following us.

Continue to Part III

Images:

-

“Remember Michael Stewart” button, 1984. © Collection of Patricia A. Pesce, New York Photo: Allison Chipak. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2019

-

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s The Death of Michael Stewart, 1983. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar Photo: Allison Chipak. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2019