The Tenement Museum’s Jason Eisner and his daughter return to Green-Wood Cemetery, and in the process of aiding a few people in their search for the grave of artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, uncover a haunting moment in Lower East Side history. A story told in three parts and two paintings. Read part I now.

Great Reads, New York City History

Haunted by History Part III: Memory Phantoms

October 30, 2020

Stealing a glance back at the Basquiat fans, I see them taking photos of his headstone, digital memorabilia. At my daughter’s request, we are heading to the cemetery hill to watch the trains. Atop this hill we see the setting sun flickering off the D-train cars as they turn and angle into the underground station at 9th Avenue. The view from this spot attracts my daughter, and with her on my shoulders, she sees the world from a higher place than I ever will. While she delights in watching the subway, I remain brooding over Basquiat.

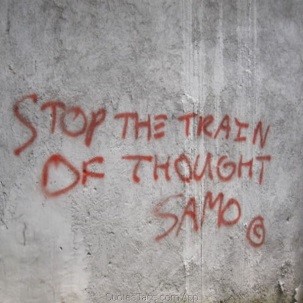

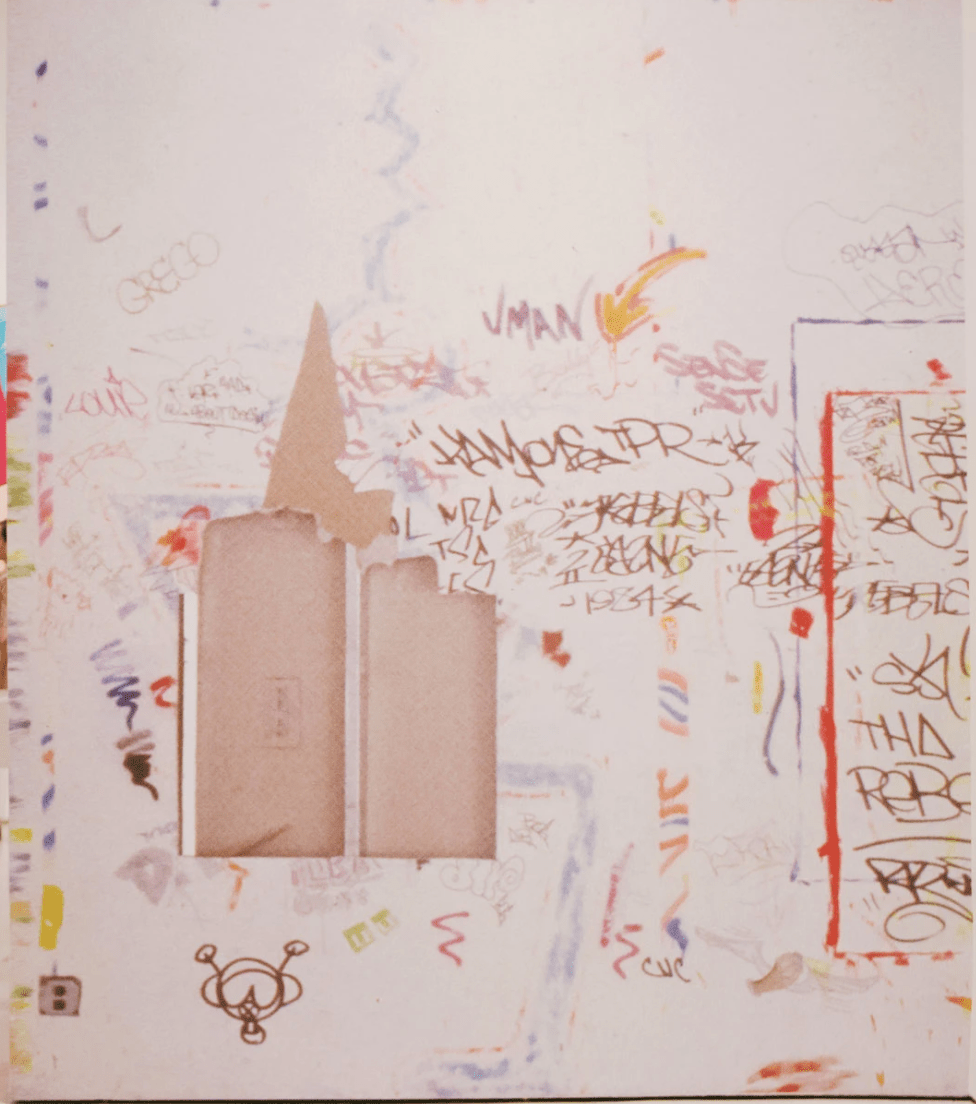

As a teenager, Basquiat was also drawn to the D-train. In 1977, he partnered with Lower East Side graffitist Al Diaz in promotion of SAMO – a fictional character of Basquiat’s invention. SAMO broke from the emerging graffiti tradition by spray-painting earthy poetic phrases throughout the LES and on the D train.

Basquiat and Diaz worked together in anonymity, with SAMO being the artifact of their sustained art performance. Increasingly, however, Diaz felt Basquiat taking control of SAMO, and following a 1979 Village Voice article exposing their identities, the creative collaborators went separate ways. SAMO is Dead marked LES walls and trains announcing the end.

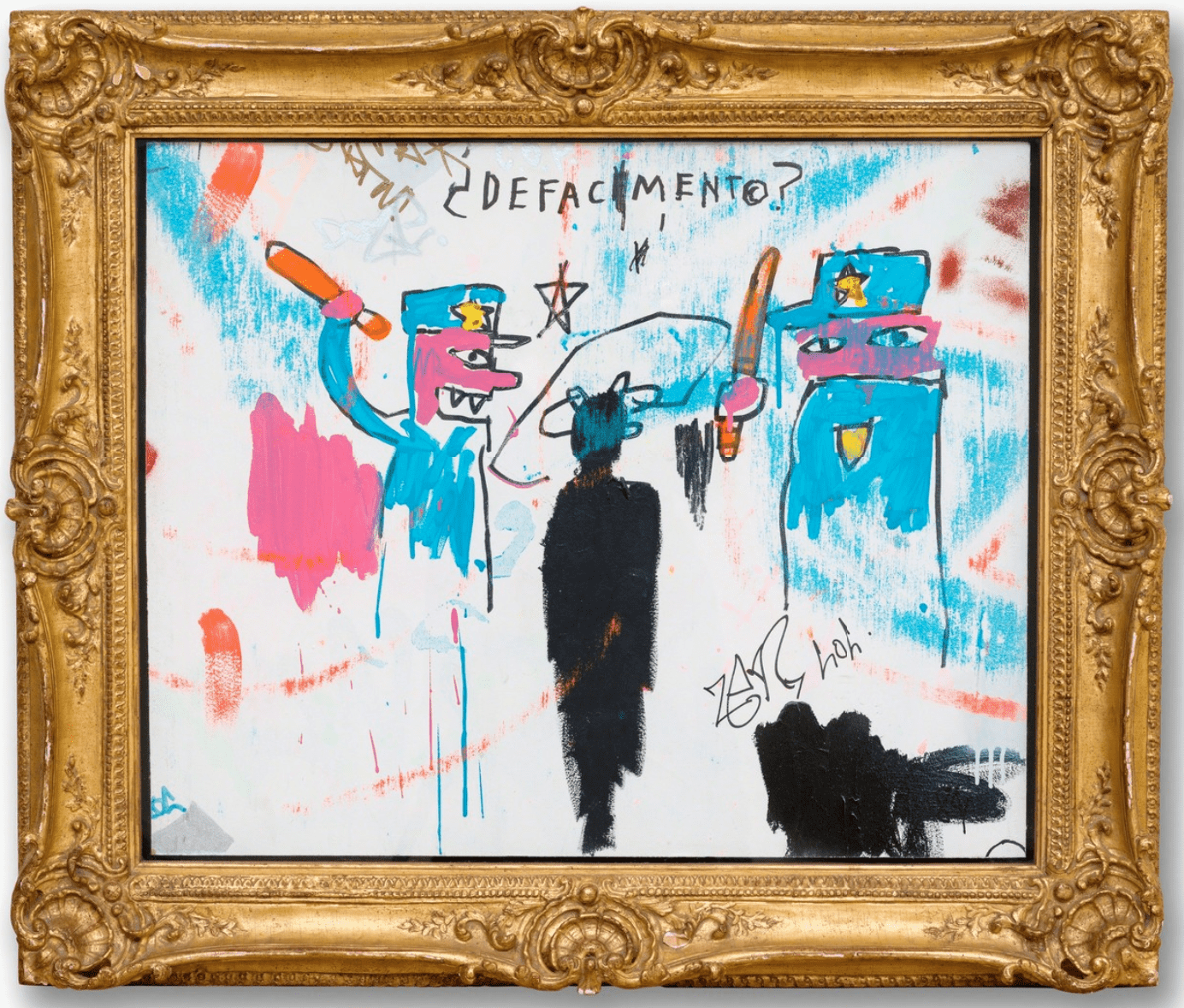

As SAMO died, Basquiat, the charismatic artist of the Downtown scene began to take shape, and these foundational years as a street artist helped form his later painting. My thoughts return to Basquiat’s 1983 painting, “The Death of Michael Stewart,” where floating above the central figure, the word “Defacement” hovers between question marks. During the 1980s, New York City police were aggressively cracking down on graffiti – framing it as a defacement of public property. Basquiat’s use of question marks pushes the word beyond literal interpretation, and considering Michael Stewart’s condition following his encounter with the police, the painting asks, “What is being defaced here?”

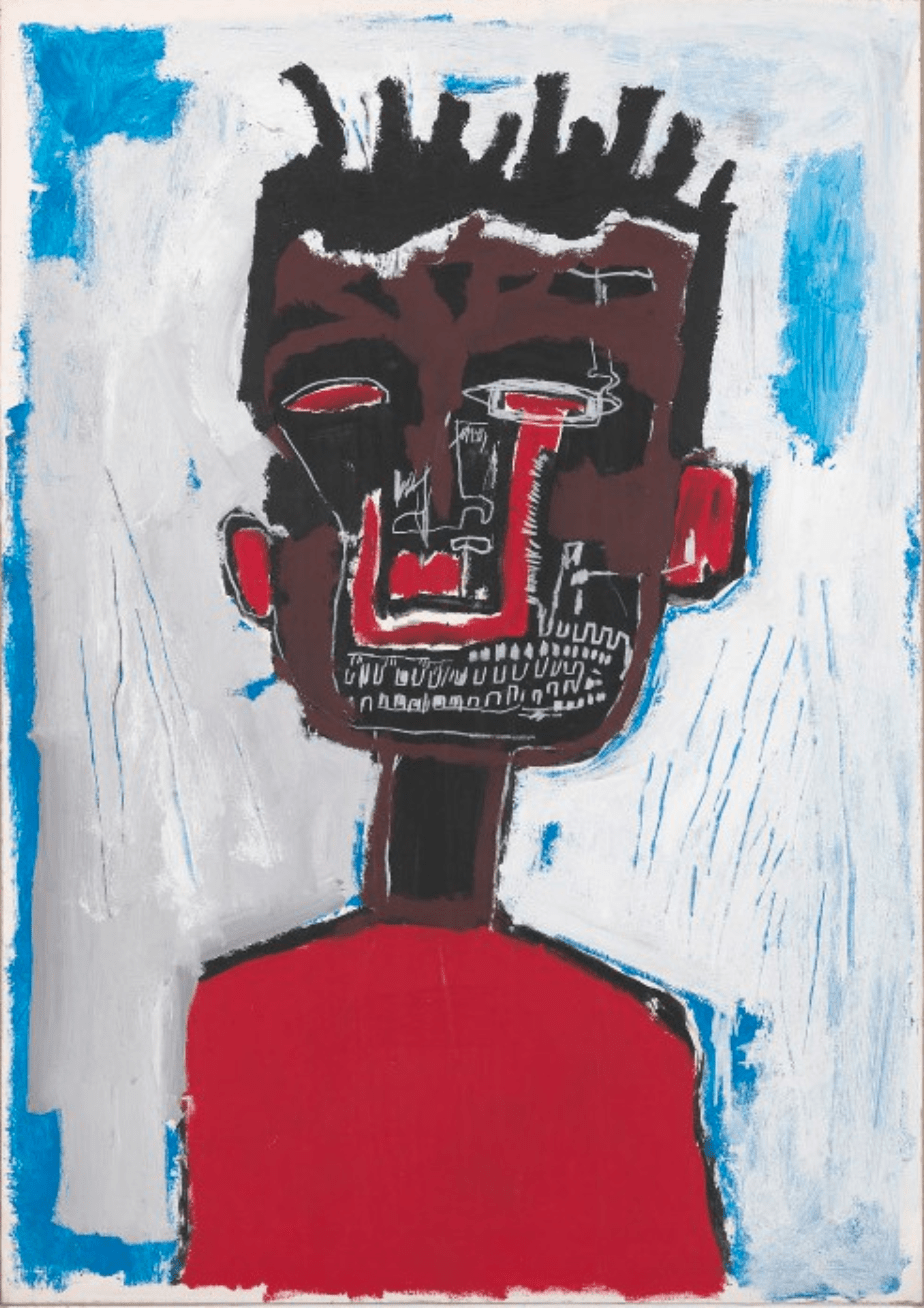

The question pulls me back to Basquiat’s 1984 “Self Portrait.” His neck is a flattened black box surrounded by a heavy brown outline. His burning red eyes engulfed in pools of black, like bruises. A crimson stream pours from his left eye. There is no delineation to indelicate his arms. Are they being held behind him as when handcuffed? Lilian Conrad, the head nurse on duty when the police brought Michael Stewart into Bellevue, reported that his neck and eyes were swollen and badly bruised. I shudder as I recall Basquait’s haunting self-reflection about Michael Stewart, “It could have been me.” In this self-portrait, is Basquiat attempting to connect to Michael Stewart- to see himself through the grave? Is this the reanimation of Michael Stewart as Basquiat- a restless spirit brought back to life to confront us? Challenging us to bear witness and to reform, or to remind us of our haunted history.

My daughter tilts about restlessly on my shoulders. She is ready to go home, and wants to lead the way Setting her down and taking her hand, she guides me back to Basquiat’s grave passing familiar trees and stones along the way. We are surrounded by objects of memory.

Basquiat’s painting, “The Death of Michael Stewart,” too became a memorial object after Keith Haring encased it in a decorative guided frame. Before, that it was an impulsive emotional image painted on a studio wall- a ‘defacement’ of Haring’s creative space. Beyond the need to process the moment, Basquiat may have intended it as a warning to the graffiti writers who coalesced around Haring- especially if they were Black. And while it may have been a cautionary message for Black artists, it was too, a reminder to white artists of their privilege- particularly in relationship to the police. Whatever the intention, the image was important enough for Haring to preserve. In 1985, before he moved to a new studio, Haring had Basquiat’s image cut out of the wall. Framed and hung above Haring’s bed, the image was recontextualized as piece of art, elevating the subject matter to a place of cultural significance.

For Haring, the painting is layered with memories: of Michael Stewart, of the calls for social justice, of his old studio and all the friends who passed through it; and of Basquiat, who was found in his Great Jones Street loft on August 12, 1988, dead from a drug overdose. Two years later, on February 16, 1990 Keith Haring would also die, of AIDS-related complications.

Both Haring and Basquiat were high-profile cultural figures whose lives were cut short by epidemic illness. Basquiat died from an addiction to heroin in the same year that new cases of AIDS resulting from shared needles exceeded the cases attributed to sexual exchange in New York City. That same year also marked the appointment of Dr. Anthony Fauci to the newly created Office of AIDS Research. Connections to our current moment – fears of pandemic illness, outrage over police violence, and an unreconciled legacy of anti-Black racism – dwell in the shadows when iconic figures like Basquiat take the spotlight of our collected memory.

As I resolve to continue excavating these connections, a lonely young figure approaches us. Their imploring eyes and twisted paper map suggest another lost Basquait fan. “Excuse me… they’re going to close soon and I wanted to find Basquiat’s grave. Do you know where it is?”

My daughter says, “Guy!” I translate this for the lost searcher, but my reply echoes back to me as a cryptic message: “What you’re looking for is right behind you, but you passed it over. Let’s take a second look.”

History is layered, complicated, and messy. However, compressed mythic narratives prevail. Narrow, simplistic, lacking nuance, these mythic narratives interrupt our ability to connect the present to the past, or to make informed choices for the future. Unless we take a second look, we’ll be forever haunted by history.

Leaving the Basquiat fan behind us, I hear my daughter exclaim “Go-Go!” We’re nearing her stone dog friend and it’s getting late. Lifting her onto my shoulders again, we hurry to the gate before closing because I, for one, am not especially keen on being around when the stone dog comes alive every night, to stand guard over this place of memory.

Images:

-

SAMO graffiti

-

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s The Death of Michael Stewart, 1983. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar Photo: Allison Chipak. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2019

-

Self-portrait, 1984 © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

-

The Keith Haring Foundation; Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar; [cropped from Mary Inhea Kang for The New York Times]