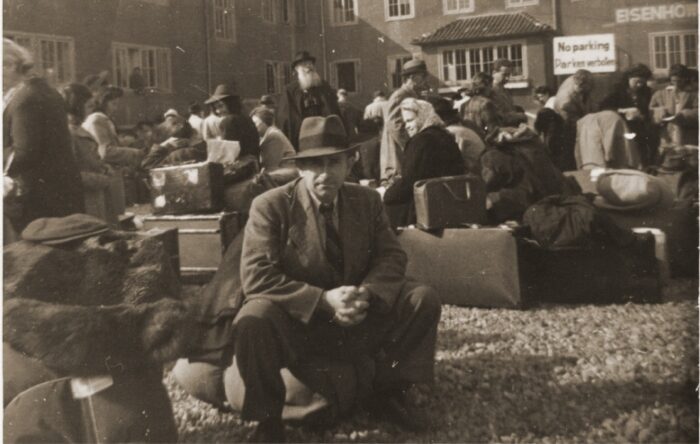

Watching the footage of packed aircrafts taking off from Kabul, I couldn’t stop thinking about Saifullah, an Afghan refugee who stayed in my home seven years ago. As I think back on his story, I question what responsibility we have as Americans when our policies harm others. What responsibility do we have as humans to help one another?

At first, I was apprehensive, when one day about seven years ago my roommate texted me asking if I would be okay with a man staying in our apartment for a couple of days. We were three early-twenties women living in a single bathroom Brooklyn apartment, but we agreed that it was the right thing to do. Saifullah needed lodging when housing organized by a refugee resettlement group fell through. We made up the couch and showed him how the shower worked. He didn’t speak much English, so we didn’t get to know each other very well, but one morning, as I was eating breakfast, I noticed a settlement house flyer and an English language workbook that Saifullah left on our dining table.

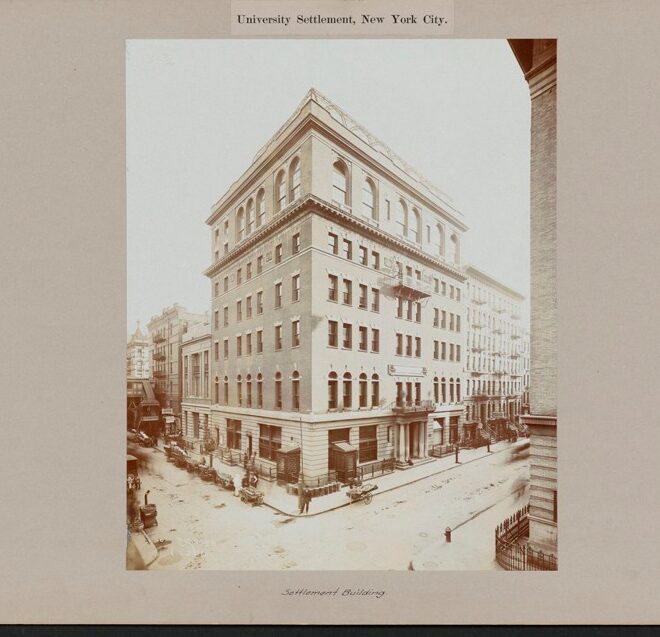

Settlement houses have been serving newcomers to New York City since the turn of the twentieth century. Spotting the flyer connected his story to many others who came before, including many of our former residents. Like Victoria Confino, a 14-year-old Sephardic girl who moved to New York from Kastoria with her family. T