Blog Archive

Lives Gone in a Puff of Smoke

About 3:45 am on the morning of March 14, 1905, Isidor Davis noticed a glare. Davis was a wine maker in one of the two basement stores of 105 Allen Street. The glare was coming from the sink in the other basement storefront, a restaurant owned by Stanifols Lisnik; it was a fire in a painters funnel. Davis took off his coat and attempted to lift the funnel out of the sink and extinguish the fire in the back lot, but as he lifted the funnel, the flames shot through his coat and he dropped it. He ran to his apartment to warn his wife and children and grabbed a quilt to snuff out the fire, but the quilt only caught fire as well. Within minutes, the whole hallway was engulfed in smoke and flames.

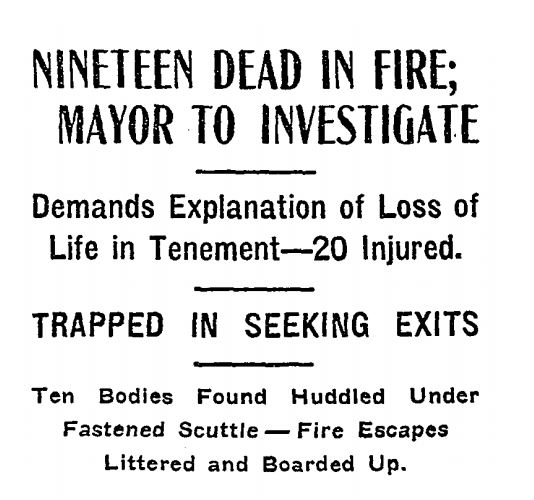

The fire would spiral out of control and become a two-alarm blaze that would kill more than 20 people, many of them children. One entire family was killed in their apartment, and there was not one of the twenty families in the building who did not experience a loss or injury. Many of the bodies were burned beyond recognition.

Even in 1905, two alarm fires could generally be contained quickly or escaped from safely, so what made this blaze so deadly? The building was a death trap; the fire escapes were boarded up and blocked with garbage and debris and the door to the roof was locked from the outside, preventing escape. Most of the victims were found near these useless openings.

The police were notified minutes after the fire began, and two policemen, Dwan and Quinn, woke tenants and dropped a baby to safety from the fire escape. Officer Dwan even ran through the building, his clothes on fire, with a little girl clinging to his neck. He fell from the fire escape, but landed so that the little girl was safely on top of him. Dwan was treated for a broken shoulder, fractured hip, possible internal injuries, and cuts and burns; he lived to receive a medal from the people of the East Side.

The fire shocked the city, with Mayor McClellan promising to investigate why the fire escapes were unusable despite the fact that the Tenement House Department inspections for 105 Allen Street always came back as satisfactory. The Tenement House Department said that the landlord, Celia Leiner, and the tenants would clear off the fire escapes, only to block them again.

Crowded fire escapes remained a danger for tenement dwellers, as this 1930's poster shows us. Image courtesy the Library of Congress.

On March 25th, a jury found Mrs. Leiner guilty of gross negligence for locking her skylights from the outside and censured the Tenement House Commission for failing to properly inspect the building, which was unsanitary and had lighting violations.

Other than that, nothing changed.

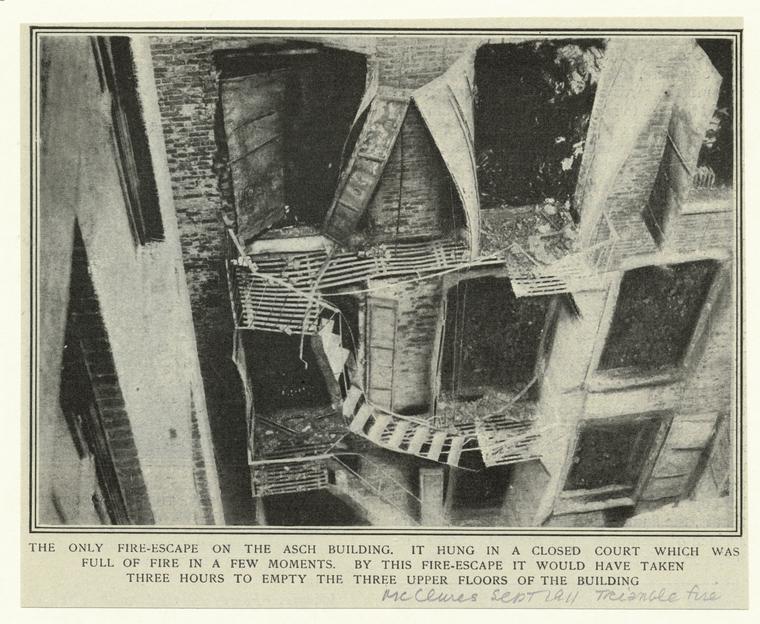

The quickly melted fire escape from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Image courtesy the New York Public Library.

It wasn’t until 1911, when the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Washington Square and the Dreamland amusement park fire in Coney Island, Brooklyn signaled the beginning of modern fire codes – outward opening doors, longer ladders for firemen, and other laws. Both of these conflagrations continue to capture the modern imagination as a time when in New York, a new country, young people often risked their lives in order to make their family’s better.

In The Museum of Extraordinary Things, the most recent novel from Alice Hoffman, Coralie Sanders and her star-crossed lover Eddie Cohen experience this chaotic time in New York’s history, and two of its most influential tragedies.

Firemen extinguish the last embers of the Dreamland amusement park with a roller coaster in the background. Image courtesy the Library of Congress.

Ms. Hoffman will be at the Tenement Museum on March 26th at 6:30 pm to discuss her new book. More information is available here.

– Posted by Lib Tietjen