Blog Archive

Made of Star Stuff, And Some Other Stuff, Too

Last year, in the middle of a wet November day, I received a phone call from my mother while on a lunch break.

“I have some news,” she said. “I just got the lab results back and — Oh, I have to go, I’ll call you back.” She hung up.

Several hours of hand-wringing later, I gave in and rang her back first. She sells perfume for a living, so the only lab who would be contacting her would presumably be a medical lab, relaying some kind of serious issue. I’d come up with several horrifying possibilities just in the time it took her to answer the phone.

“Oh. No,” she said. “The DNA test came back today.”

She lives in Florida, while I live in New York. We keep in contact with each other pretty regularly, but I feel like I would have known if she’d appeared on Maury or Jerry Springer. I had absolutely no idea what she was talking about.

My mother was born in London, and for the last twenty-something years she was living undocumented in the United States. It was an incredibly stressful handful of decades for her, particularly in the last few years, where life for undocumented citizens became extremely difficult for anyone without a social security number. But she finally received her U.S. residency last autumn, which has had some unexpected side effects. With her own social security number, she was able to open up a proper bank account, which gave her a debit card. Which opened up her world to the wonders of online shopping.

Among the odd clothing and accessories from websites I’ve never heard of, and numerous restaurant deals from Groupon, she had purchased a DNA test from ConnectMyDNA.com.

“It said I came from Belarus, Oman, and Chile,” said my mother, laughing. “I have no idea.”

If anything in a shop has a Union Jack flag on it, my mother will buy it. She’ll tell anyone and everyone about the time she met Princess Diana, she’ll grouse about how the villains in any action movie is always vaguely English, and she’ll spends many evenings watching what she calls “gentle comedies” on PBS. In short, she is extremely proud to be British, the same way many people are proud to be where they come from. But my mother is not uninterested in her history. She covets every family photograph, and she’s fascinated by the concept of lineage and ancestry. It’s a quality she passed down to me, too.

As far as she was aware, her family line had been in England forever. She knew of no relatives from Belarus, Oman, or Chile.

At the Tenement Museum, we love to end tours showing the relations of the families we discuss on our tours. Standing in the parlor of Natalie Gumpertz from our Hard Times tour, decorated how she might have back in the 1880s, and looking at a photograph of her great-great grandchildren — is truly a highlight of what we do here. It adds another contextual layer to the stories we tell. The immigrants who arrived here were not just striving to achieve a sustainable life for themselves and their immediate families. Each of the 7,000 people who passed through the walls at 97 Orchard Street were a part of a legacy that continues to this day; themselves just another link in the chain of their own ancestry, but one that changed the direction of that line forever.

We don’t work with DNA tests, though. We rely on oral histories, faded records, slips of paper lost in the cracks of the floorboards. Different lenses to view the human migration experience.

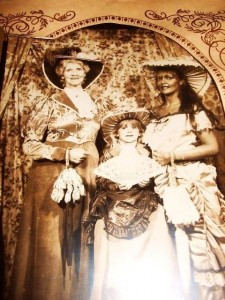

Despite appearances to the contrary, this photo was not taken in the 19th century. It it actually a picture of me, my mother, and my grandmother at a convention center over twenty years ago in Boca Raton, Florida.

A few weeks later, it was Christmas morning, and I was home for the holidays. Breakfast had been eaten, gifts had been open, and we were beginning the time honored festive tradition of lazing about, when my mum called me over to the kitchen table, along with my older brother and younger sister.

“I have one gift left,” she said. “But I only have one, and I don’t want to look like I’m playing favorites by choosing to give it to one of you.”

“What,” we said, “are you talking about.”

She put a Hershey’s kiss under one of three cups, and moved them all around, but the presence of a heavy tablecloth, as well as the fact that my mother never worked for a carnival, didn’t make the game very challenging, and my brother picked the right cup on the first guess.

“Okay,” said my mum, pointing. “You get it.”

“What?”

She’d ordered another DNA test for one of us to take. However, it hadn’t actually come in the mail before Christmas Day, but it did just happen to come in the days between my brother returning home and me flying back to New York, so the honor ended up falling to me. It was like CSI: Coral Springs, Florida — my mother the no-nonsense detective, cornering me in my own home and watching me swab the inside of my cheek to send off to the labs, trying to pin some heinous crime on me.

I was back in New York before I got my results, which were emailed to me at one in the morning. I’m not totally sure what I was expecting. Belarus, Oman, or Chile, on some level.

My top two results was Croatia and Iran. My “surprise connection” was Ethiopia. Okay.

More detailed information is hidden behind a paywall. The website gives some interesting facts about your regions of origin, facts like, “the city of Zadar is home to the world’s first Sea Organ that creates its music only by the action of the wind and waves” or “the Persian cat is one of the world’s oldest breeds. They originated in the high plateaus of Iran where their long silky fur protected them from the cold. “ Neat stuff, but I didn’t say how any of this related to me. I don’t know of any relative from Croatia or Iran or Ethiopia. I was tempted to write the whole thing off as my mother being conned by the internet, praying that I hadn’t just delivered a DNA sample to a mad scientist who might use it for cloning or framing me for a murder. Or making me a main attraction in some ill-conceived theme park.

But then I delved deeper into the information I was actually given, and I began to understand a little more what my mother had paid for. The website clearly states they’re not an ancestry product. They deal with that complicated tangle of genetic material that I barely understand on a good day. It’s a lot about alleles and loci, things half remembered from high school that I might have absorbed at one point through osmosis (that’s my one science joke, I do in fact know that’s not how osmosis works). But I understand that my DNA and yours aren’t as different as one might expect. “We know that over 99% of human DNA is identical,” the FAQ on ConnectMyDNA.com explains. “It’s less than 1% of our DNA that makes us unique; that tells us what our physical characteristics are like. We know that in some way we are all connected as human beings.”

A popular theory of human evolution states that human migration occurred over centuries, the human race beginning in Africa and spreading throughout the rest of the world. ConnectMyDNA.com uses a database to find those genetic traces from tiny fragments in our DNA, as theorized by that equation, the Hardy-Weinberg principle. Looking at these fragments, they compare them with similarities in our population groups around the world. The test has nothing to do with my own heritage, but how I relate to the population on a genetic level.

In a sense, a test like this shows something incredibly specific as well as broadly expansive. My DNA is as personal to me as my fingerprint or my phone number. Yet at the same time, it is a global phenomenon, linking human beings to one another on a microscopic scale, in ways we often cannot detect and in ways we certainly can’t change. Human migration has been occurring for millennia, people moving to new parts of a shifting Earth while evolving and reproducing. It’s as fascinating to me to see those traces of genetic ancestry, as though we were talking about my own great-great grandparent’s immigration story. It highlights the fundamental parts of ourselves that have remained unchanged, despite a constantly changing world. That deep within us, regardless or where we started or where we end up, humans have always just been humans.

- Post by Gemma Solomons, Marketing & Communications Coordinator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum