Blog Archive

Noah’s Arc: Diversity aboard New England’s Whaling Ships

Everyone has their great white whale, that distant dream that forever eludes capture. For me, this whale was actually a whale, okay a whale tale, Moby Dick, the mother of all whale metaphors.

Despite my various literature degrees, no syllabus had included it and no professor had encouraged it. Digesting this American epic seemed a responsibility like jury duty: time-consuming but ultimately rewarding. And with the idea of summer reading still lingering in my subconscious, I decided to begin immediately and finish that august story by the end of the season.

No one said it was going to be easy… but it is! Moby Dick is swimming with unexpected pleasures and revelations. Moby Dick, a novel published in 1851 about the whaling industry, superficially has nothing to do with Lower East Side tenements, but diversity is one of the major surprises of the story.

Herman Melville takes the reader almost directly to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where whaling has created the Lower East Side in miniature – an immigrant hub. New Bedford was already relatively diverse; the Wampanoag Native Americans had called the area home for 300 years, and in the golden age of whaling (during which Moby Dick is set), runaway slaves and freedmen also gravitated toward New Bedford because of its relatively tolerant Quaker ideology. The whaling industry also brought new citizens to New Bedford, especially from the Azores, an archipelago 800 miles off the coast of Portugal. The Azores were the first port of call for many whaling vessels and ships, which would stop there to acquire supplies and more sailors.

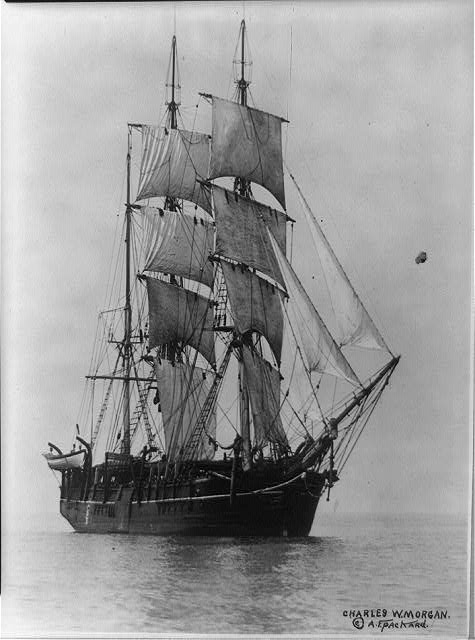

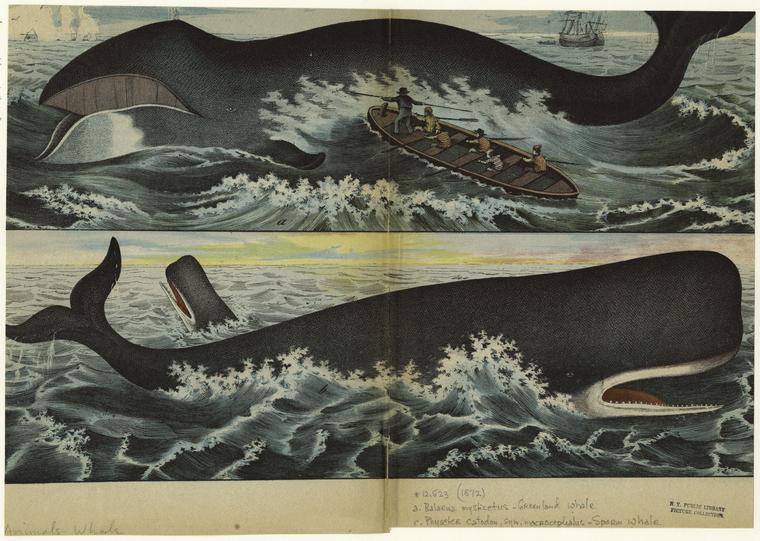

Talk about group bonding! Whaling expeditions have nothing on your intermural softball club. Trips at sea could last some three years, and the ships would travel from pole to pole, circumnavigating the globe in search of enormous, intelligent mammals to slaughter for their fat. Life on a whaling ship on the high seas was dangerous enough, even before you and your buddies lowered into a little 30 foot whaleboat to row up to a whale twice the size of your boat to stick it with a sharp piece of iron. If all went according to plan, it was merely messy and terrifying. If anything went wrong, it was deadly.

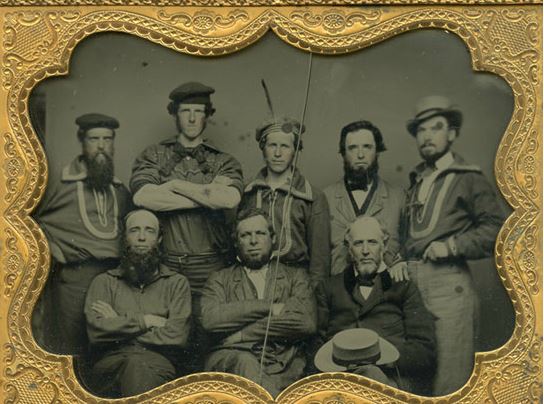

Sailors would join the crew from Africa, South America and Asia. While some would join only to disembark at the next port, others became important members of the whaling community. Surprisingly, the stratifications aboard the ship were mostly dictated by a sailor’s seriousness and his commitment to the voyage, more than his nationality. One of the pleasures of reading Moby Dick is the joy and equanimity with which the narrator observes the spectrum of humanity on board the Pequod. Sure Melville’s narrator, Ishmael, deploys all manner of racial slurs of the era, but his observations always conclude that, superficial differences aside, there is more in common between men than incontrast. Over and over, Melville’s Ishmael finds dignity in men he has been raised to find “savage” or “uncivilized.” Melville’s work however, somewhat highlights the hypocrisy of the time. Despite all of Melville’s tolerance and respect for the rainbow of ethnicities he represents on the Pequod, the tales are not entirely rosy. Records do show that it was hardest for African American sailors to rise in the ranks, even in the egalitarian world of a Quaker whaler.

Crew member of a whaling ship, probably seniors in rank. Photo courtesy of the Public Broadcasting Service.

Working intensely in life-threatening situations and living intimately in close quarters must have forced many white Americans to come to similar conclusions. Unexpectedly, whaling ships may have served as the kind of melting pot that usually occurs on crowded city blocks.

After the wane of the whaling industry (and wane it did when petroleum, an alternative to whale oil, was discovered), the textile trade continued to bring immigrants to New Bedford. Immigrants from Portugal continued to emigrate, encouraged by older whaling connections who were forming communities not unlike those here on the Lower East Side. Except of course, for the tales told around the fire on winter nights.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator

with much research support from

The New Bedford Whaling Museum

and

The PBS program “Into the Deep: American Whaling and the World”