Blog Archive

Of Memory and Survival: The Jewish American Identity

April 4, 2017

For the other parts of this series highlighting the new ethnic groups featured in “Under One Roof,” you can read Becoming “Nuyorican” and Look For the Union Label: Chinese Immigration in America

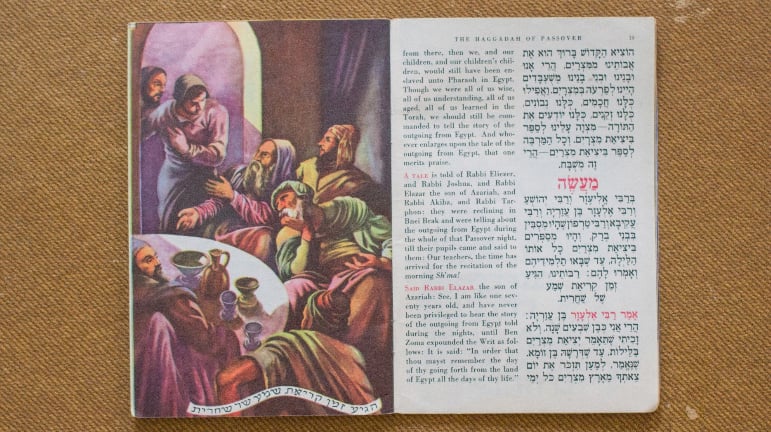

In Bella Epstein’s home, her whole family – what was left of it – would gather together in their tiny apartment on the Lower East Side to celebrate Passover, they would recite the names of the family members who had been taken from them.

The rest of the year, Bella’s mother and father wouldn’t discuss their experiences during the Holocaust if they could help it. Certainly not with their daughters.

But on Passover, the retelling of the Jewish migration out of Egypt had a powerful resonance for many displaced Jews in the 1940s and 1950s. Jews like Bella’s parents, survivors from Germany and Poland who had met in a Displaced Persons camp following the end of World War II, were some of the lucky few able to take refuge and start a new life in the United States. The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 put severe quotas on immigration, and most of the American population agreed with this policy at the time, mainly for economic reasons. Following World War I and the Great Depression, no one wanted immigrants coming in at a time when Americans struggled to get jobs for themselves. And people feared history would repeat after World War II.

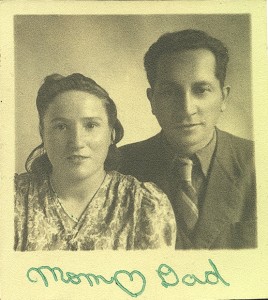

But President Truman’s 1945 directive allowed a small number of immigrants to enter the United States with refugee status. Truman famously stated, “This is the opportunity for America to set an example for the rest of the world in cooperation toward alleviating human misery.” Bella’s parents came to the country through this executive order in 1947. The Displaced Persons Act passed a year later, increasing the number of incoming refugees over the next few years, so that by 1952, there were 400,000 Displaced Persons admitted to the U.S.

Video courtesy of Critical Past

It’s hard to imagine how Holocaust refugees like Bella’s parents might have felt, arriving on our shores. But then, it’s hard to imagine any of the trauma those people had endured. One can assume it was a complicated combination of relief and despair, mixed in with uncertainty of the future and the usual cultural shock of moving to a completely new country. Not to mention, moving from hostile territory to a place that wasn’t exactly welcoming you with open arms.

We may not realize it now, but the Holocaust wasn’t thought of a singular, capitalized event for a long time after the war. For many years, exactly what was done to Eastern European Jews and others in German concentration camps was unclear, and just part of a larger number of atrocities and brutalities that occurred during the War. The sheer scale of the War meant misinformation abounded, intentionally and accidentally by both Allied and Axis powers, so the scope of what was lost took years to fully comprehend. In late 1944 to spring of 1945, three-quarters of the American population thought Germans had killed people in camps, but not nearly the right number. The typical estimate was only 100,000 people or less.

In the decades to follow, the understanding of the attempted genocide changed and expanded in the American social consciousness. Werner Weinberg, a German Jewish writer who wrote often about his experiences under Nazi regime, said, “Immediately after the war, we were ‘liberated prisoners’; in subsequent years we were included in the term ‘DPs’ or ‘displaced persons’…In the US we were sometimes generously called ‘New Americans.’ Then for a long time…there was a good chance that we, as a group, might go nameless. But one day I noticed that I had been reclassified as a ‘survivor.'”

It wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century did people begin to understand what had occurred, which coincided with the time that the concept of American Jewry began to take hold. Before that, and in the years during World War II especially, there was no real sense of a Jewish American community. Most Jews were either newly arrived immigrants themselves or first-generation. Postwar, American Jews became more politically motivated, and the desire to connect with each other only strengthened as they gained knowledge of whole families, villages, cultures, and histories being completely wiped out overseas. The Jewish American identity was created from the events of World War II.

New York’s Lower East Side has been, since its inception, a welcome sign for incoming Jews. And the Jewish history of this place – how Jews formed communities here, kept practicing their religion here, built long-lasting businesses here, raised their families here – has become fully enmeshed in what developed into the Jewish American identity as it is known in popular culture. Hasia R. Diner, author of Lower East Side Memories: A Jewish Place in America, wrote about how the Lower East Side is as integral to the soul of American Jewry as the ravaged lands of Eastern Europe. “Since the late 1940s, American Jewish memory had been bounded by these two mythic places, eastern Europe and the Lower East Side,” she said. “Each one stood, and still stands, as a point of memory, replete with an instantly recognizable set of images of people and places, described with a sensual trope built around sounds, smells, and tastes, stimulating a process of remembering even for those… who did not grow up in either place.”

Bella’s parents grew up in Eastern Europe. Then they continued to grow in 1947 on the Lower East Side, learning to reconcile their traumas in order to live here in America and raise American children, and we tell that story at our upcoming exhibition Under One Roof at 103 Orchard Street. The Epsteins, like many other Displaced Persons, were bound by two places, forming the bedrock of a new cultural identity for Jews in America. An identity based on survival, community, and memory.

- Post by Gemma Solomons, Marketing & Communications Coordinator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum