Blog Archive

Spring Cleaning? They Do It All Year!

According to the Huffington Post, Tokyo is the cleanest city in the world; New York City is ranked an unimpressive 28th, but this is not for lack of trying. The removal of garbage and refuse in New York City is a near-Herculean undertaking in a time with garbage trucks and recycling plants – imagine what it was like at the turn of the century!

New York’s Department of Sanitation is the world’s biggest, collecting 10,500 tons of residential and institutional refuse and 1,760 tons of recyclables a day (private garbage companies haul away another 13,000 tons a day). The Department of Sanitation is comprised of 7,197 uniformed sanitation workers and supervisors as well as 2,048 civilian workers, who operate a fleet of 2,230 collection trucks, 450 mechanical street sweepers, 275 specialized collection trucks, 365 salt/sand spreaders, 298 front end loaders, and 2,360 various other support vehicles. All of these people and machines work together to keep New York as trash-free as possible. Of course, this is with over 120 years of practice! Things could get a little fragrant before the Department of Sanitation, originally called the Department of Street Cleaning, was formed.

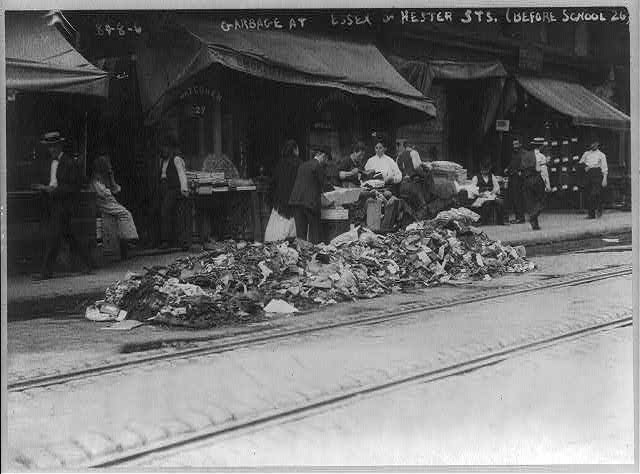

Before regular street cleaning and garbage removal, residents of working-class neighborhoods like the Lower East Side were supposed to put their garbage in garbage-boxes set in front of the tenement building, which could prove difficult as these boxes frequently weren’t there! Even when they were present, the boxes were not big enough or removed frequently enough to keep the street clean. In 1863, the New York Tribune reported that garbage boxes were little more than piles of “heterogeneous filth…forming one festering, rotting, loathsome, hellish mass of air poisoning, death-breeding filth, reeking on the fierce sunshine.” Sounds nice.

For decades, household refuse and rotting animal carcasses remained piled in the streets of the city. Not only was this extremely unpleasant, but it was also deadly. According to anthropologist Robin Nagle, “A study done in 1851 concluded that fully a third of the city’s deaths that year could have been prevented if basic sanitary measures had been in place.”

Piles of garbage at Essex and Hester Streets during a Sanitation workers strike, 1911. Image courtesy the Library of Congress.

This is not to say that people didn’t make any effort to keep the city clean; for much of the 19th century, street cleaning in New York was conducted by private carting operations who were awarded contracts by the municipal government. Not surprisingly, such a system encouraged political graft and corruption and ultimately proved ineffective. Wealthy neighborhoods could afford to continue with private street sweepers, but many working-class neighborhoods could not, and the garbage piled up again.

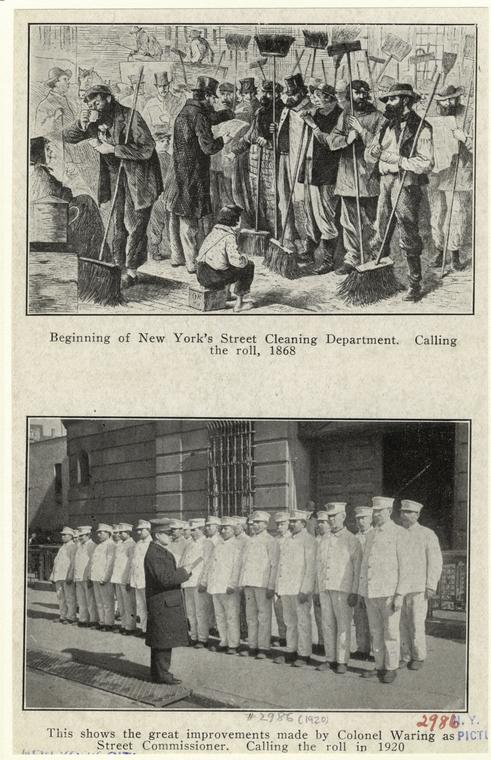

Beginning in 1866, the Metropolitan Board of Health assumed authority over street cleaning – the responsibility shifted to the Metropolitan Board of Police in 1872. Finally, in 1881, the Department of Street Cleaning was created with the specific purpose to clean up New York.

Effective street-cleaning, however, did not arrive until the appointment of George Waring to direct the department in 1895. In that year, Waring, a Civil War veteran, “reorganized the department along military lines, minimized political influence in employing workers, stressed sweeping by hand rather than with machines, and dressed street sweepers in white duck uniforms, earning them the nickname of ‘white wings.'”

While Waring’s leadership style often clashed with unions and even some of his own workers, his strategy proved very effective, and under his leadership, the Department of Street Cleaning cleared the streets of shin-deep animal, human, and who knows what else waste.

A page from a 1920 NYC guidebook shows the improvements that Waring made to the fleet of street sweepers. Image courtesy the New York Public Library.

As you can imagine, New Yorkers were rather grateful – in 1896, they threw a parade for the Sanitation workers.

The funny thing about much of New York’s infrastructure is that when it’s working perfectly, it’s mostly unnoticeable. But let’s all take a moment to thank the Department of Sanitation from saving us from the “festering, rotting, loathsome, hellish mass” of the past.

– Posted by Lib Tietjen and Dave Favaloro