Blog Archive

Summer Blaze

This cartoon from 1912 titled "New York under the Dog-Star" gives us a peek at summer time spent in heavy wool dresses and suits. Photo courtesy of the NYPL.

It is summer in the city, the 79th warmest summer in 138 years to be exact. Can you believe that there are some among us who think it should have been warmer this summer? It can be easy to romanticize the dog days as long as you aren’t struggling through them. While 2014 has proven to be fairly mild, the summer of 1896 saw the deadliest heat wave in New York City history. Circumstances both atmospheric and political contributed to the deaths of approximately 1,500 New Yorkers, many of them on the Lower East Side, during a ten day heat wave. The Mayor failed to call a meeting to address the situation until the tenth and final day.

Beginning Tuesday, August 4th officials recorded steamy highs of around 87 degrees, but this is only half the story. According to historian Edward P. Kohn, author of Hot Time in Old Town, a study of the tragedy, the instruments which recorded those “official” temperatures were mostly above street level or positioned at other locations where there was a breeze. Everywhere the humidity held steady at 90% and temperatures at street level were much higher due to heat radiating off buildings and pavements. The worst of the heat was inside tenements just like ours. Kohn estimates the temperatures could have reached 120 degrees Fahrenheit in these overcrowded apartments.

It might be generous to assume that this miscalculation of ambient temperature was part of the reason why the heat was not taken more seriously, but the deaths were due at least in part because of bureaucratic mismanagement and apathy. One unfortunate ordinance which could have made quite a difference prohibited city-dwellers from sleeping in parks. No one moved to lift this ban at any time during the heat wave. The heat during the evenings was almost as intense as during the day, only after the final day of the heat wave did evening temperatures drop to 70 degrees. Many deaths were the result of residents trying to sleep on roofs, or children seeking relief on fire escapes and falling or rolling to their deaths. Residents also sought respite by sleeping by the East River which offered its own precariousness as several sleepers rolled into the river.

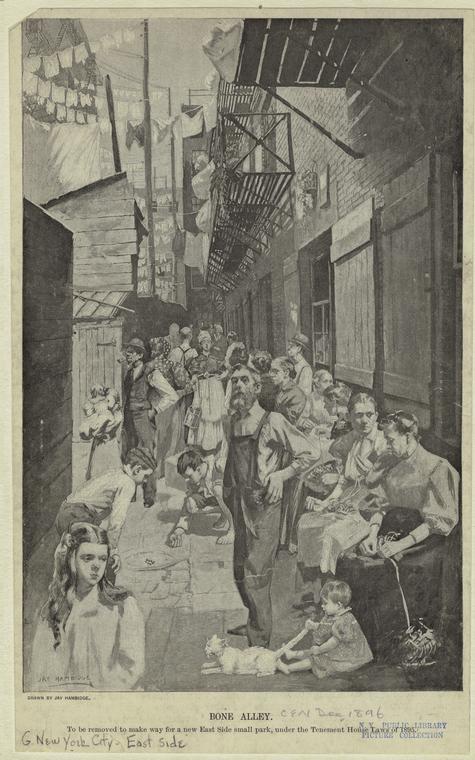

A portrait of Bone Alley from the 1896. This former notorious slum on the Lower East Side was in the heart of the worst suffering. Photo courtesy of

Because heat stroke takes many different forms, death certificates from the ten day period do not paint a clear picture of the suffering; (Kohn offers that while many of the symptoms, such as asthma and diarrhea were recorded, however only in some cases did “heat stroke” literally appear.) However, compared to the same ten days in 1895 the number of death certificates in the city for 1896 was nearly double. As today, the very young and the very old were the most at risk but certain other professions also carried particular heat risks. The city commissioner of public works, One of the only officials to react to the heat, adjusted the schedule of his laborers allowing them to work during the coolest hours of the day and called for city workers to flush the streets with water to cool temperatures. We need only consult the SPCA to note that another group of day laborers, over 500 horses, had already died from heat exhaustion by between August 4th and August 11th.

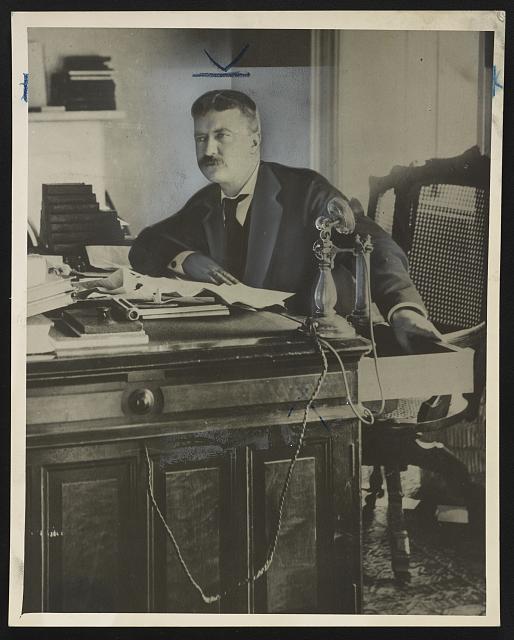

Theodore Roosevelt as a young police commissioner. Roosevelt kept a cool head in the crisis and was one of the only officials to attend to the victims. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

One of the only other city officials to attend to the crisis was a then little-known Police Commissioner named Theodore Roosevelt. Some believe that his thoughtful responses to the heat wave helped start Roosevelt on his path to power and ultimately the Presidency. What was Roosevelt’s quick and relatively inexpensive fix? To distribute ice among the city’s poorest and hottest. Roosevelt suggested that the city buy and distribute ice and helped to supervise the distribution of 100 pounds of ice in 10-pound blocks through police precincts. In letters to his sister, Roosevelt noted police corruption even in the face of this obvious tragedy, with officers taking bribes from wealthier parents and withholding ice from some of the poorest.

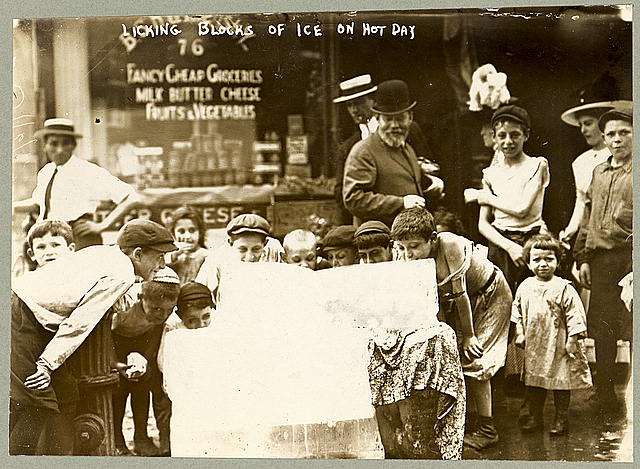

This much jollier scene shows children on the Lower East Side enjoying ice on a less brutal summer day in 1912. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Eventually, the heat broke but the tragedy helped make clear the desperation of tenement living and, as Kohn believes, may have contributed to the Tenement Housing Act reforms of 1901 which addressed some of the worst health and hygiene offenses.

–Posted by Julia Berick