Museum staff, however, use a completely different strategy to control rodents and insects than the rat–catchers and heavy poisons of the past. Rather than responding to each infestation by calling an exterminator to eliminate pests, the Tenement Museum contracts with a professional pest management company that uses Integrated Pest Management (IPM) to monitor the building and guide decisions.

Influenced by the environmentalist movement and the ecological consequences of years of wholesale pesticide use, IPM became national pest control policy under Presidents Nixon and Carter in the 1970s. IPM is used in a variety of industries from agriculture to museum management to zoos. It is a decision-making process that focuses on finding solutions to pest infestations by fixing the reasons why pests are there in the first place instead of automatically exterminating them with toxic pesticides. Each museum space at the Tenement Museum has discrete insect sticky traps which are monitored for potential infestations by the Collections Manager and Pest Management Contractor every month. This monthly pest monitoring information is evaluated against environmental monitoring information to guide treatment and prevention decisions. IPM gets to the root source of the infestation by altering the conditions that attract pests to the resource and by changing human behavior. Chemical controls may be used as a last resort, but the museum’s IPM plan guides which pesticides may be used, and tracks every time they are deployed.

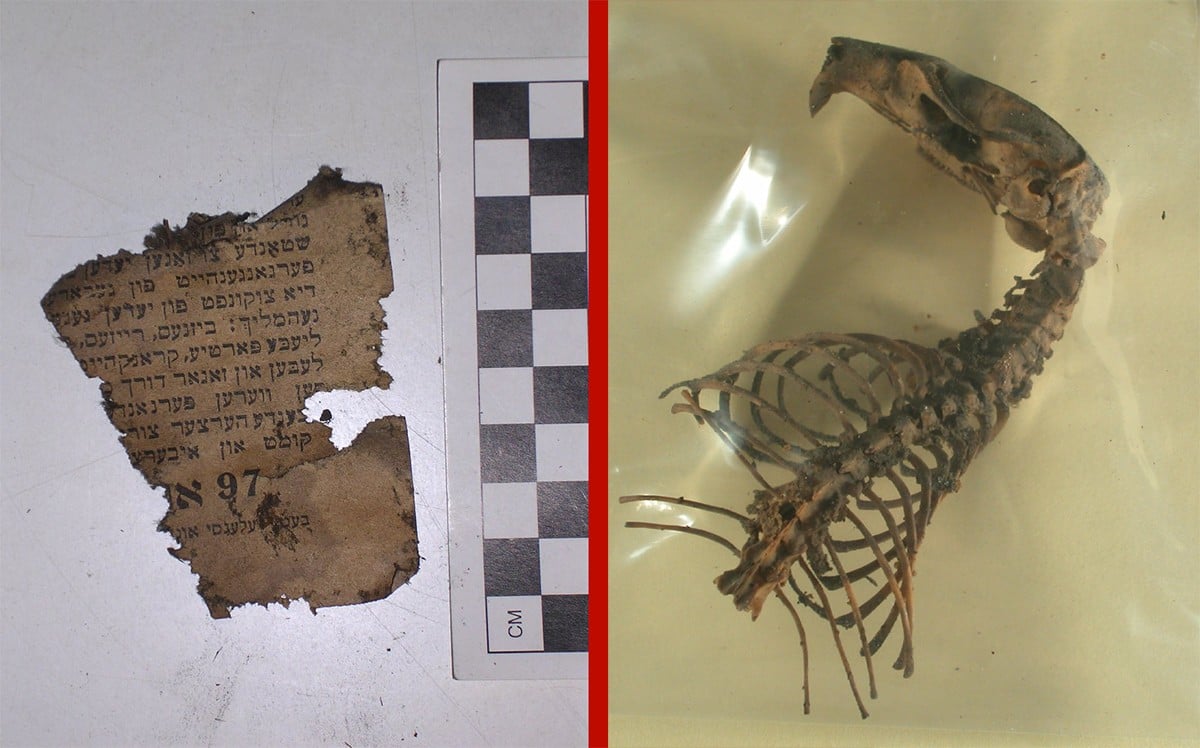

Rats and mice still occasionally make 97 Orchard Street their home. However, by using the IPM process to monitor their presence, control access, and inform decision-making, the Tenement Museum prevents damage to its collections and buildings while protecting the health of visitors and staff.

Stay tuned for more interesting discoveries when we begin our next preservation project, stabilization work inside 97 Orchard Street, slated to begin in 2021!