In 1954, the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education struck down the legal basis of school segregation outlined in Plessy vs Fergusson and maintained by the false “separate but equal” doctrine. The ruling had a profound impact on school districts in the Jim Crow south, where the codified, legal structures of segregation could now be targeted and eliminated by federal integration programs. Brown vs Board would prove much more difficult to enforce in the de facto system of school segregation that existed in northern cities.

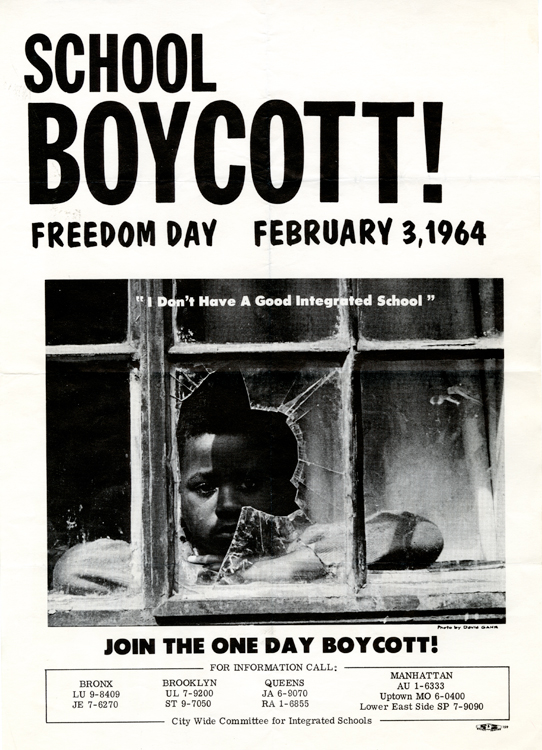

In the decade after the Supreme Court ruling, schools in New York City experienced an increase in segregation along with declining conditions in public schools for Black and Puerto Rican students. This pattern of entrenching segregation was the result of Redlining and housing discrimination, as well as the public-school system’s antiquated zoning laws and fierce opposition to integration among white parents. The number of schools considered segregated grew from 52 in 1954 to well over 200 by 1964.

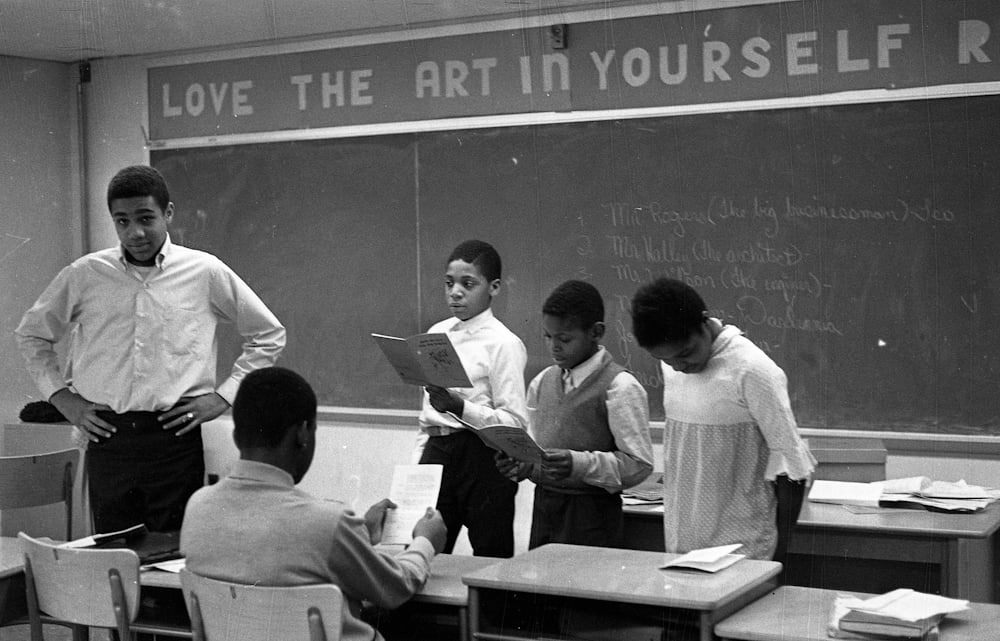

Activists also drew attention to the worsening conditions in minority majority schools. While public schools in white neighborhoods were only half full, Black and Puerto Rican schools were overcrowded, underfunded, and poorly staffed. Harlem, New York’s largest Black neighborhood, had only a single high school by the early 1960s. In Harlem and other neighborhoods such as Bedford-Stuyvesant and the Lower East Side, students were forced to attend school in half day shifts to accommodate the overcrowding and teacher shortage. Public schools in Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods also lacked libraries, gymnasiums, or special education classes, most notably English education. In 1964 only 18% of Puerto Rican students on the Lower East Side were fluent in English at or above their grade level.