Blog Archive

Tradition (and Individual Talent): How the Stories of the Shtetl became a Broadway Sensation

One of the best-loved musicals of all time returns to Broadway this fall, with fanfare, glossy print advertisements, and plenty of press. When the curtain rises on this new production of Fiddler on the Roof however, that Broadway sparkle will give way to something a little less glamorous: the shtetl.

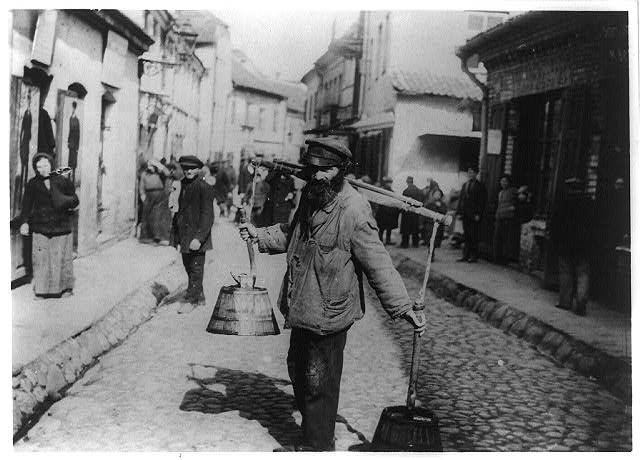

A shtetl (for those who did not spend their childhood dancing to the original Broadway soundtrack on the family turntable) was a small market town in pre-World War II Eastern Europe characterized by a large Yiddish- speaking Jewish population. Though of course living in a quiet community of like-minded people can have its advantages, the shtetl was not necessarily something to sing and dance about. These were small settlements where Jews were often persecuted; their lives were regulated, and they lacked any significant political clout. The stories of this community have been consecrated many times, and passed on by many bubbleh, but perhaps the most famous scribe of the shtetl was Sholem Aleichem, born Sholem Rabinovich in 1859 in what is now the Ukraine.

A poster for a yiddish production of a Sholem Aleichem play in 1938 in Roxbury, Mass. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

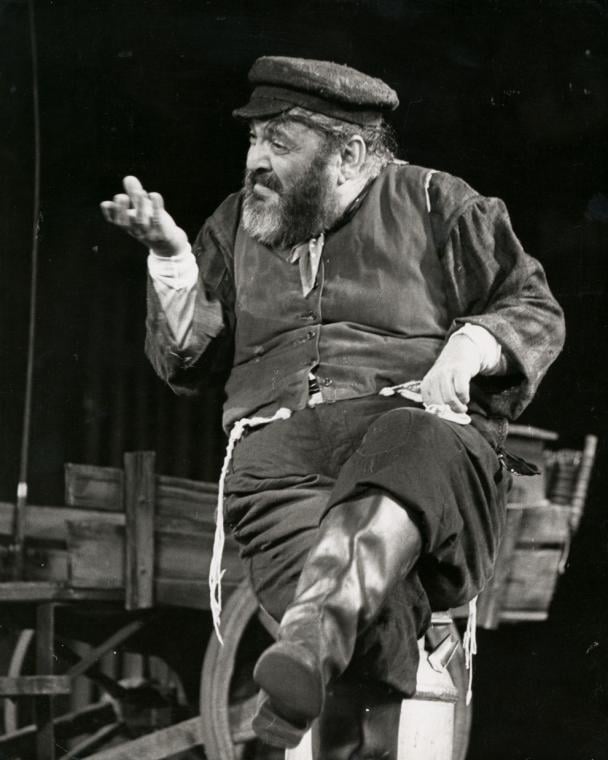

Fiddler on the Roof is based on some of the nearly 40 volumes of stories and plays of Sholem Aleichem, all originally written in Yiddish. His works eventually became important cornerstones for Yiddish theater in New York. It is hard for us to imagine now, okay now that we’ve discussed the shtetl it is not at all hard to imagine, but when Fiddler on the Roof first opened in 1964 it was a bit more of a long shot.

Old hands at Broadway magic, Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick nevertheless found themselves searching for a hit in 1960. Fortunately, someone had a translation of Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye stories. These stories might have at first seemed an unlikely match for a mid-century Broadway musical. So how did the Yiddish stories of a tiny, beleaguered Jewish town become a smash-hit Broadway show?

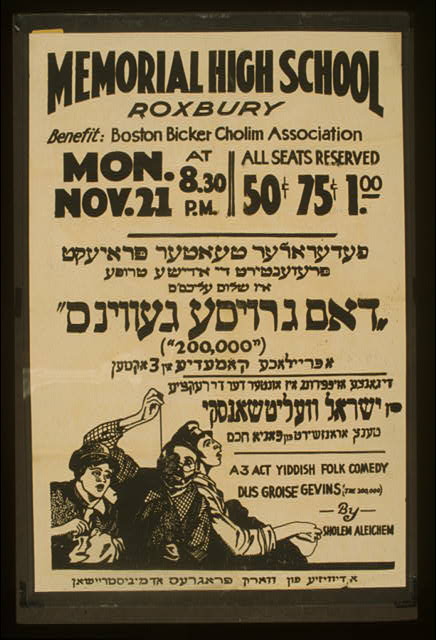

Fiddler was the longest running production at the time of its close in 1972 and already a blockbuster film. It is actually a tale that will wrap you like the warmest shawl in the coldest Russian winters. When the team began working Aleichem’s material into a musical, they were hard-pressed to find investors, and perhaps for good reason. Even Jewish New Yorkers who left (in many cases fled) Eastern Europe couldn’t imagine their experience as exactly crowd pleasing. The creative team finally convinced an initially reluctant Jerome Robbins to choreograph and direct the show. Robbins, like second-generation immigrants everywhere, had done what he could to distance himself from his father’s Eastern European Jewish past, but with Fiddler he decided to finally face the music. Robbins had just traveled back to the tiny Polish town where his father had grown up and found that in post-war Poland the Jewish community he had visited as a child was totally gone. Some historians speculate that this was the necessary push Robbins needed to commemorate his heritage.

Soon Robbins was (respectfully) sneaking himself and his cast members into Orthodox Jewish weddings to gather impressions of Jewish traditions. Robbins was inspired to choreograph the movement for the play when he witnessed a drunken party guest striding with bravado at one such wedding. For the play, Robbins conceived of the equally bold “bottle dance” where dancers made increasingly daring movements while balancing a bottle on their heads. In the original production the bottles were real and so was the threat of broken glass. By opening night the largely agnostic directorial team was exchanging heartfelt tokens of the Jewish faith: a yarmulke, a shofar, and a mezuzah. Robbins’s father was thrilled by the production, commenting, “How did you know all that?” according to Alisa Solomon, author of Wonders of Wonders: a cultural history of Fiddler on the Roof.

While the play is about a very specific part of Jewish identity, it also became about embracing one’s roots and about tradition in a much more universal way. Audiences loved the production, including Lin-Manuel Miranda, known for his immensely popular portrayal of another New York tribe, Puerto Ricans, in “In the Heights,” and a reinterpretation of U.S. history in “Hamilton.” By the time the musical traveled it was a huge hit in Japan, with a Japanese director reportedly asking an American involved with the production how American audiences could have liked a story that is so Japanese!?

So the hit-making aspect of Fiddler on the Roof turns out not to be dazzle after all. The narrative that attracted New York audiences, Jews, gentiles, Puerto Rican teens, and Japanese citizens was really an enduring tale of change and tradition.

Real Old-World glamour. A Jew in Vilna in 1922 carries water. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator

With a great debt of research to

Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of “Fiddler on the Roof”

By Alisa Solomon

Illustrated. 433 pp. Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt & Company