Blog Archive

What Lies Beneath

October 10, 2018

If someone opened up the floorboards of your home, what would they find? A grain of rice that dropped to the floor? A scrap of junk mail? A lost button? There’s something surreal in imagining the tiny pieces of ourselves that seem so small and unimportant at the time, suddenly made significant when found decades or centuries later by another.

From August to September, I sorted through a sampling of detritus that had settled bit-by-bit beneath the floorboards of 97 Orchard Street from 1863 to present day. Some of it had fallen through on its own, like a stray bean or onion skin lost in the business of cooking dinner. Other objects were clearly brought there by those ambitious and ever present NYC residents: rats and mice. These unintentional yet marvelous archivists left their mark in the form of tiny gnawings along the edges of cigarette cards, the precious fabric scraps they made their nests from, and even their own mummified bodies hidden beneath a hearth once warmed by a coal burning stove.

At least ten bags of debris were removed from the floors of Apartment 13 during a conservation project on the fourth floor in the spring of 2014. In a continuing effort to protect 97 Orchard, and make it accessible to the public for years to come, the floorboards were opened up to reveal the old plaster keys that pressed between the lath when the ceiling of the apartment below was first installed.

These keys, however, age and break and sometimes need extra help to support the ceiling. Our conservation team from Jablonski went in from above, creating artificial keys with resin injected into the void between the floorboards. The project resumed on a different floor this summer (2018) to stabilize the ceilings of second floor apartments to the north. Several more bags of debris were collected.

The bags from Apartment 13 were labeled by room and the directional quadrant where the detritus was found, and then brought to the cellar of 97 Orchard. It was there that I set up a pair of sawhorses and a screen to sift before the open bulkhead of our building.

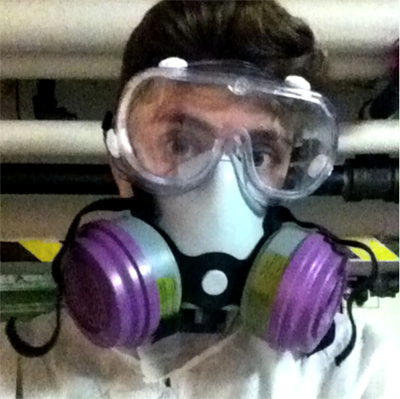

As I went through the bags a number hazards had to be kept in mind — toxic rat pee from a century ago, lead dust, splintered wood, rusted nails —all manner of nasty things I didn’t wish to take into my lungs or carry home on my clothes. So, during the sifting phase of the project, this was my work uniform:

As I worked through each bag, I found that they all had different personalities. The first, from the parlor, was filled with a dust so fine it looked like smoke as it curled from the screen. The second and third, both from the kitchen, was a darker, heavier soil that didn’t seem to cling as much to the coveralls I wore. And the fourth bag barely had any dust to sift through at all. It contained heavy, jagged pieces of wood and chunks of plaster that threatened to tear through the bulging plastic. This bag ended up being my favorite, because among those bigger pieces of debris came bigger finds. All of the more notable pieces found in abundance were accessioned into the permanent collection under the banner of Apartment 13.

Here are a few of my favorites. The first is this little friend:

I was growing tired of the monotony of searching through horsehair laced plaster, which I’ll admit was initially very exciting, when I found this mouse amid the debris. I started cheering, muffled of course, by the rubber of my respirator.

Another discovery was a rectangular piece of cardboard which, while dirty and featureless at first glance, stood out to me as something worth keeping. During the accessioning process I was able to dust it off and the print of a woman was revealed.

Cora Dean, the card proclaims—though her name must be taken with a grain of salt as these particular cigarette cards were not known for their accuracy. They were produced during the 1880s to drum up interest in W. Duke Sons & Co Cross-Cut Cigarettes, and while searches bring up one Cora Dean in a month-long Broadway production of John Hudson’s Wife in 1906, no other information seems to remain.

Sometimes, the finds are more unsettling, like this small pharyngeal jaw found in one of the kitchen bags. It caused such a visceral reaction in me that I just had to show it every staff member I came across.

Certain fish (like Sheepshead fish, for which Sheepshead Bay is named) have startlingly human-looking teeth in rows that line their throats. This cluster looks similar to Freshwater Drum. However much this artifact made my skin crawl, it did provide insight into what was on the menu in the kitchens of 97 Orchard. I also found the vertebrae of chickens and fish, cleanly cut beef bones for stews, stone fruit pits, chestnut shells, and even scrap advertisements for M. Prechter’s Rye Bread, a bakery started in the 1880s that continues to sell Jewish Rye bread today.

Then I found a coffee bean. I’m certain coffee beans have fallen in similar fashion through the floorboards in my own home and I have given them little thought. But something about picking up this one, dropped by someone a century ago and left quiet and untouched for all those years, felt profoundly special to me. All of these things have a sense memory that calls back every hand they passed through. In finding them, they become a bridge that closes the gap between people of the past and present, showing how shared our lives and stories continue to be.

Blog posted by SJ Costello

SJ is an Educator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, illustrator, and general story-teller with a focus in 19th century American history.