Part I: The American Dream

In 1904, Barney Cohen immigrated from Warsaw, Poland to New York City. At the age of 17 he was beginning a new life, making a living by selling pots and pans. Sometime between 1910 and 1911, Barney found space to rent as a boarder of the Rogarshevsky family in Apartment #8 of 97 Orchard Street. Young, hopeful, and ambitious – propelled by the opportunity to move up the class ladder – Barney’s life seemed to be built around chasing the ‘American Dream.’ His decision to board with the Rogarshevskys was likely made in an effort to save money. But this thrifty move put Barney in touch with something unexpected – his future life partner.

The Rogarshevskys’ youngest daughter, Bessie – herself young, hopeful, and working as a sewing machine operator – perhaps felt a kinship to this aspirational single man. One thing led to another, and before too long, “He fell in love with my mother and they got married,” as their son, Irving, described it in a 2006 oral history interview.

It’s a classic story: the daughter and the boarder run off together. The thing is, they only ran off to 96 Orchard (directly across the street), and there started a family of their own. Their second child, Irving, was born on August 19, 1913, at that address. The Museum learned a great deal about the family through Irving’s oral history. 93 years later, when Museum researchers asked him about his life on Orchard Street, Irving replied without hesitation:

“Earliest memory I have is the pushcarts, and dodging in and out between the pushcarts, and playing with the fellows. And there wasn’t much room to play ball, and there wasn’t any traffic then. We didn’t have the traffic you have now.”

Play is at the forefront of Irving’s memory. And not just any play… playing in the street! Despite stern warnings all across America, street games prevailed in most urban environments, where concrete and cobblestone stood in for playing fields. Irving and his friends (or fellows, as he calls them) seemed to be running wild, inventing games, and being mischievous in and around an adult world. However, Irving’s Orchard Street fellowships disbanded after his family moved away.

Barney Cohen’s rise seems to follow the immigrant entrepreneur’s success story- expanding from peddling kitchenware to owning a pressing iron machine business on 8th Street. As the business grew, so did the Cohens’ wealth and status. It is tempting to conclude that the Cohens’ new financial place informed their decision to move away from the cluttered, aging Lower East Side and its reputation of poverty. But the Cohens’ move to the Bronx, a veritable promised land with abundant parks, suggests another reason: the opportunity for their kids to play in nature. Regardless of their motive, by 1924 the Cohens seemed on track to fully realizing the ‘American Dream.’ Barney had come a long way. The teenage immigrant who started life over as a pots-and-pans man had worked to become a wealthy business owner and loving father of three. But in the summer of 1924, on their way back from a trip to Coney Island, Barney suffered ‘an attack’ that he didn’t survive. What doctors had misdiagnosed for years as chronic gas turned out to be appendicitis. At the age of 38, Barney Cohen’s American story prematurely drew to a close.

While sorrow and loss may have lingered, life moved on for the Cohens. After Barney’s death, Bessie reinvented herself as a small business entrepreneur. The Cohens remained in the Bronx, and with the inheritance Barney left behind, Bessie opened a Jewish summer camp for boys called Camp Cascade in Sullivan County, New York. Irving repeatedly used the phrase ‘happy times’ to describe this period. However, the stock market crash of October 29, 1929 and the subsequent downturn put a strain on Bessie’s business venture, until eventually, according to Irving, “the Depression took everything away.” Left with nothing but their history, the Cohens returned to the place where their family story began: “to Grandma’s house, there [at] 97 Orchard Street.”

Their return to 97 Orchard Street challenges the ‘ever onward and upward’ narrative baked into the ‘American Dream.’ The Lower East Side, after all, was supposed to be a place you moved away from, not back to. This aspect of the ‘American Dream’ both obscures and diminishes the stories of thousands upon thousands of people, who, like the Cohens, made their way back to (or remained on) the Lower East Side.

During the years the Cohens were away, the Lower East Side had physically transformed, and in many respects was an entirely new place. Highly restrictive immigration legislation passed in 1924 had a trickle-down effect, manifesting in depopulation and widespread vacancies. The 1930 census for 97 Orchard reflects this trend, recording only 7 occupied units out of a total 16 apartments. Landlords neglected their aging tenement houses, in many cases simply closing them off to residents. Once a thriving crowded neighborhood, the Lower East side became a blighted ghost town, with a reputation of being “America’s most considerable and most incorrigible slum.”1

The narrow and perpetually congested Allen Street, popularly referred to as, “The Street of Perpetual Shadow”2 because above it spanned the 2nd Avenue Elevated train line, was targeted for reform. Plans to widen Allen Street by 87 feet were being proposed as early as 1926, the objective being to “transform the whole Lower East Side and bring what is now a dilapidated district, a veritable stepchild of the city, once again to the family of New York.”3 As Manhattan Borough President Levy asserted, “This particular section of the city will soon become one of the garden spots of Manhattan.”6 Five years passed before the city awarded the contract for the continuation of the project south of Delancey Street, but following the official July 13, 1931 announcement, the Meehan Paving and Construction Company went swiftly to work.4 Between August 5th and December 14th, the demolition of over 100 tenement houses was completed.5

The Cohens returned to 97 Orchard in the midst of this construction project. Because they lived in one of the rear apartments, the Cohens got to witness construction teams leveling tenements directly behind them. By 1932, after all the dust settled, the view outside their parlor window was entirely different. Rather than a cavern of rear yards and the rear facade of tenements, the Cohens saw a sun-drenched open space, with a bench-lined parkway sandwiched between north and southbound lanes of traffic, and the sprawling iron skeleton of the 2nd Avenue Elevated with train cars shuttling to and fro.

Irving’s recollection of their Depression years highlights his rear window view:

“I used to sit by the window and watch the 3rd Avenue El go by, and visualize and imagine all the people going by, wondering where they were going, what they were doing. It was a form of entertainment. You had no other entertainment- you didn’t have television. In fact, I built a little crystal radio set that worked fairly well.”

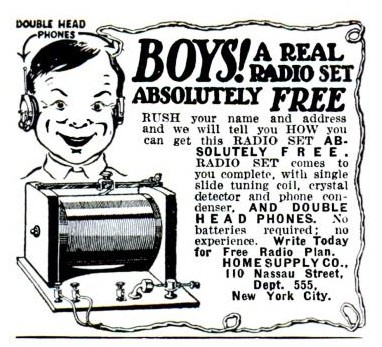

This memory, like his earliest recollection, reveals an imaginative playfulness. In 1931, when the Cohens moved into Apartment #4 at 97 Orchard Street, Irving was 18 years old. Perhaps too old for playing in the street, but not fully an adult, Irving built a world of wonder between wistfully looking through the window and tuning in to whatever stations he could pick up on his crystal radio. During his lifetime, Irving saw the rise of radio from a small-scale hobby/expensive novelty item to a full-fledged affordable commercial product. Indeed, so widespread was the consumption of this new technology, that Congress deemed it important enough to measure; the 1930 United States Census enumeration asked whether or not the household owned a radio set. Results from this census indicate that 40 percent of American households owned some form of radio.7

Do-it-yourself crystal radio sets became widely available, many of them promoted as premiums for brand-name consumer goods. These low-cost, easy-to-assemble crystal radios were largely marketed to adolescent boys like Irving. Poor quality and inconsistent reception didn’t stop crystal radio users from tinkering with the dials, tuning into whatever broadcast they could catch. Rather than listening through speakers, crystal radio users had to wear headsets to hear a broadcast. As a result, crystal sets were less communal than table-top or cabinet model radios. One can imagine Irving wearing a headset and sitting near the parlor window watching the elevated train rattle along, while searching the airwaves for the new sounds of jazz, the latest comedy or adventure serials, or news.

But Irving’s time as an adolescent on Orchard Street involved more than leisure hobbies:

“I went to work. My sister went to work. And eventually my mother went to work, too… It was a hard life on the East Side, but we were happy. Nobody had anything. Everybody was poor. And nobody knew they were poor. And life went on. We made a life for ourselves after the Depression took everything away.”

The combined efforts of the entire Cohen family renewed their financial stability. Though their financial status never matched what it was before the Depression, they saved enough to return to the Bronx. The waning Depression and the Wartime economy aided in the personal recovery efforts of families across the United States. In the midst of this personal and national recovery, Irving was drafted into World War II- his American Reality moved along a different path from the one mapped in the ‘American Dream’, but does that mean it was any less successful, dynamic, or heroic? Irving remembered that the Depression years were both hard and happy because, it seems, he was able find space for play and leisure despite life’s unpredictable and surprising sorrows and hardships. Orchard Street is where the Cohen family started and started over again… it was so much more than a place you moved up and out from. To give Irving the final words:

“We always liked the East Side… Orchard Street brings back fond memories. I loved Orchard Street.”

Footnotes:

1 A Redevelopment Plan for the Central Section of the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Candeub, Isadore, p.1 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1948

2 “Allen Street Reclaimed” The New York Times, August 6, 1931

3 “Widening of Allen Street” I. Montefiore Levy, The New York Times, February 16, 1926

4 “Contract Awarded to Widen Allen Street” The New York Times, July 14, 1931

5 Pike and Allen Street: Center Median Reconstruction, Achaeological Documentary Study, AKRF, Inc, p.16, 2010

6 “Allen Street Reclaimed” The New York Times, August 6, 1931

7 Radio: The Internet of the 1930’s, Smith, Stephen. American Radio Works, http://www.americanradioworks.org/segments/radio-the-internet-of-the-1930s/