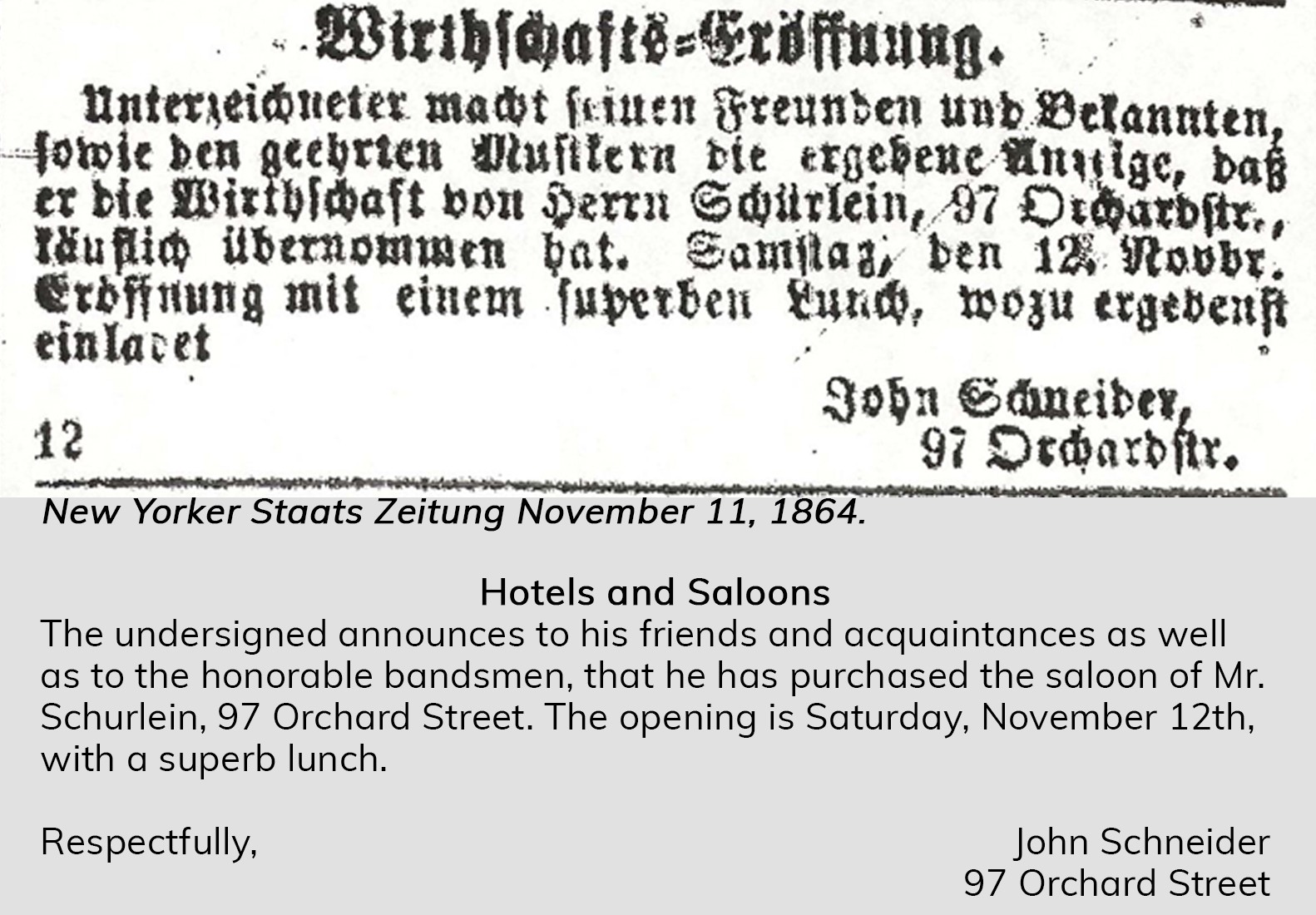

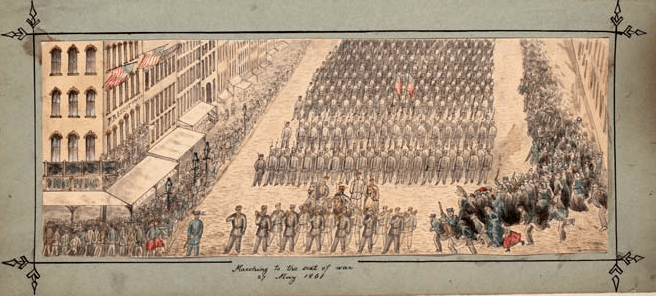

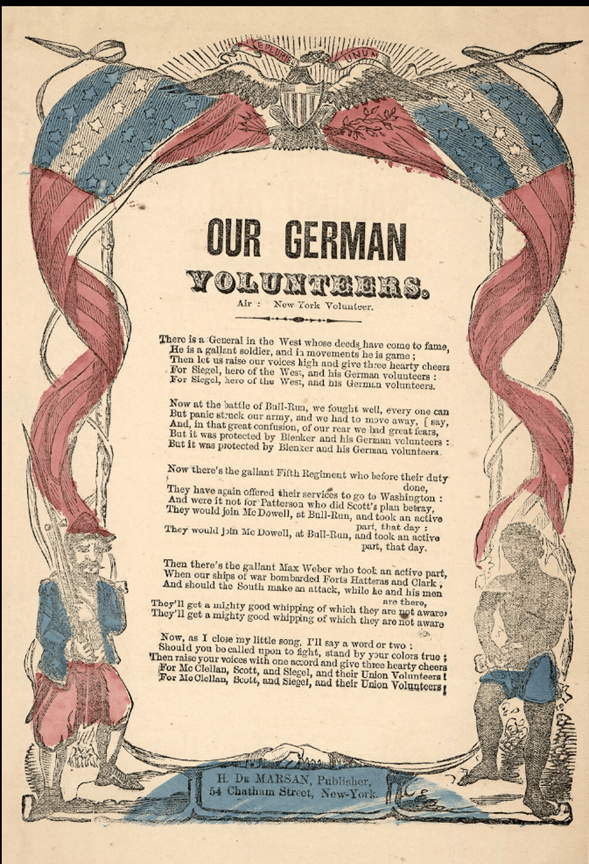

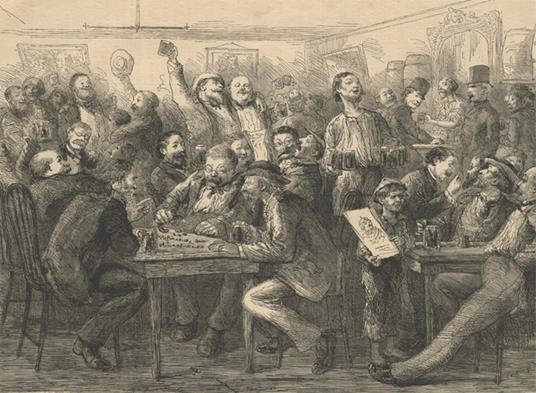

Stepping into John and Caroline’s saloon as a friend or acquaintance, you might struggle to talk over the music or sing along with it. You might find people remembering their old life in Germany, or their old life in America, before the Civil War. You might find people trying to forget their current struggles, or their recent memories of battle and hardship. You might hear people reminiscing about their time in the war – victories and defeats, friendships preserved and friends lost. But no matter how they passed the time here, people in John and Caroline’s saloon were negotiating their place in America. Along with lager bier and superb lunch, these saloons offered a space for the Germans in America to be Germans in America- a space where expressions of pride revolved around a sense of belonging to both an old and new home, at the same time.

1 Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Military Statistics with Appendices, 1868 p.172

2 Keller, Christian B. Chancellorsville and the Germans, 2007, Fordham University Press p.15

3 Brisk, Barnett, Memoirs of Barnett Brisk 1850-1869, 1910 (handwritten) Circa 1970 (typed transcription), p.31

4 New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, 58th Regiment NY Volunteer Infantry Unit History/ Civil Ward Newspaper Clippings https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/infantry/58thInf/58thInfCWN.htm

5 Kamphoefner, Walter D. and Helbich, Wolfgang, The Letters They Wrote Home, Germans in the Civil War, 2006, University of North Carolina Press, p.121

6 Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Military Statistics with Appendices, 1868 p.172

7 Thompson, Kathleen Logothetics, Civil War Discourse, A Blog of the Long Civil War Era http://www.civildiscourse-historyblog.com/blog/2017/6/7/flying-dutchmen-the-xi-corps-at-chancellorsville

8 For more on this see Keller chapters 1,2, and 6

9 Kaelin, Michael, Coequal Heirs. The Civil War, Memoey, and German-American Identity 1861-1914, 2015, Duke University p.41

10 Kamphoefner, Walter D. and Helbich, Wolfgang, The Letters They Wrote Home, Germans in the Civil War, 2006, University of North Carolina Press, p.82

11 Schetcter, Barnet, The Devil’s Own Work, The Civil War Draft Riots and the fight to Reconstruct America, Walker Publishing Company, 2005 p.217