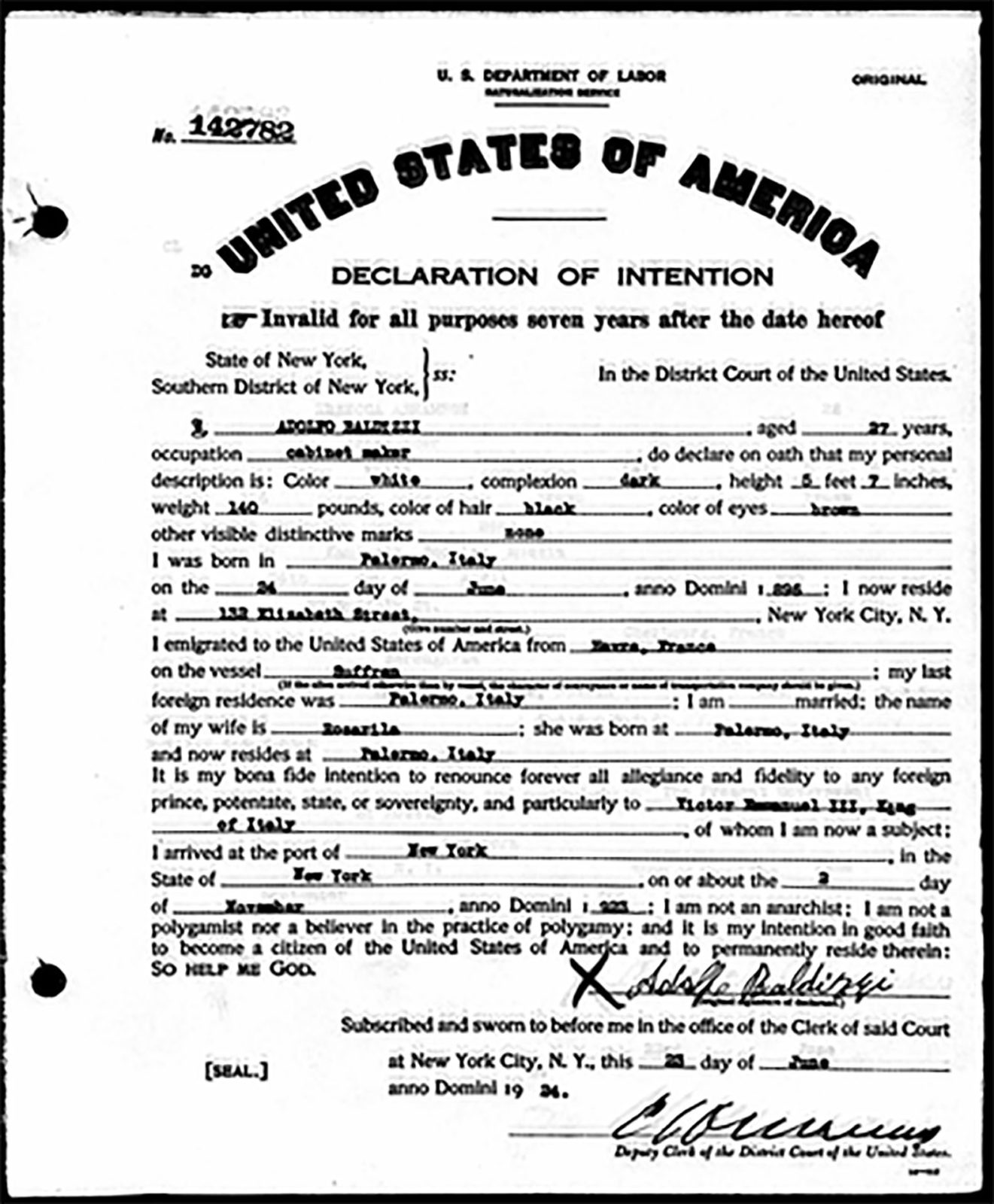

His departure from Sicily aside, Adolfo’s process for immigrating and his initial declaration of citizenship indicates he was going about things ‘the right way’. Yet, Josephine almost proudly states otherwise:

“My father came here illegally and so did my mother…. My mother came here as an American citizen. [laughs] The nerve they had- let me tell you. To leave your family and come to a strange land! Definitely took courage. You know? That took courage.

“Now, I can understand my father… a man just married… wanted to make his way. And there was no money to be made in Europe. I guess they figured, you know, that America was paved with diamonds and gold in the streets- this is what they used to tell me. I used to hear that story over and over. They came here because they thought they were going to find money in the streets, you know. And they found out it was tough.”

Oral histories are indespensible sources, but they can lead to confusion and occasionally contradict additional primary source material. Josephine’s memory of her father’s ‘illegal’ entry juxtaposed with the apparent truth of the documents underscores the fallibility of oral histories. However, regarding Rosaria’s immigration, the documentation and Josephine’s oral history align.

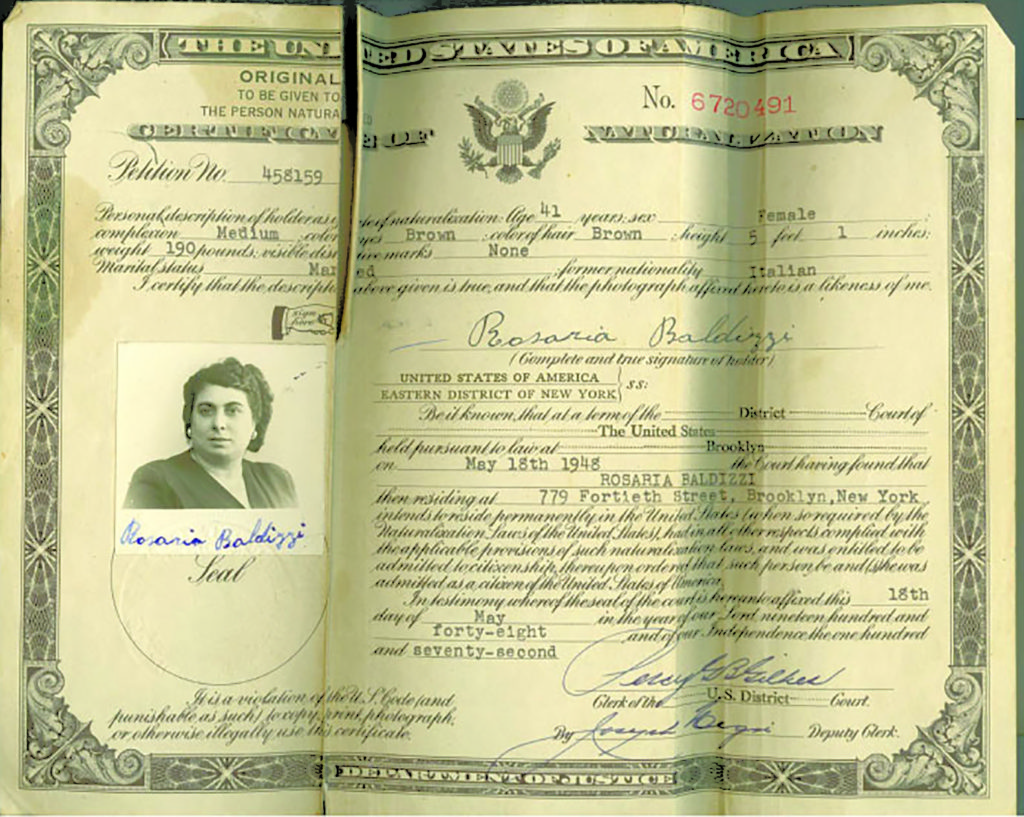

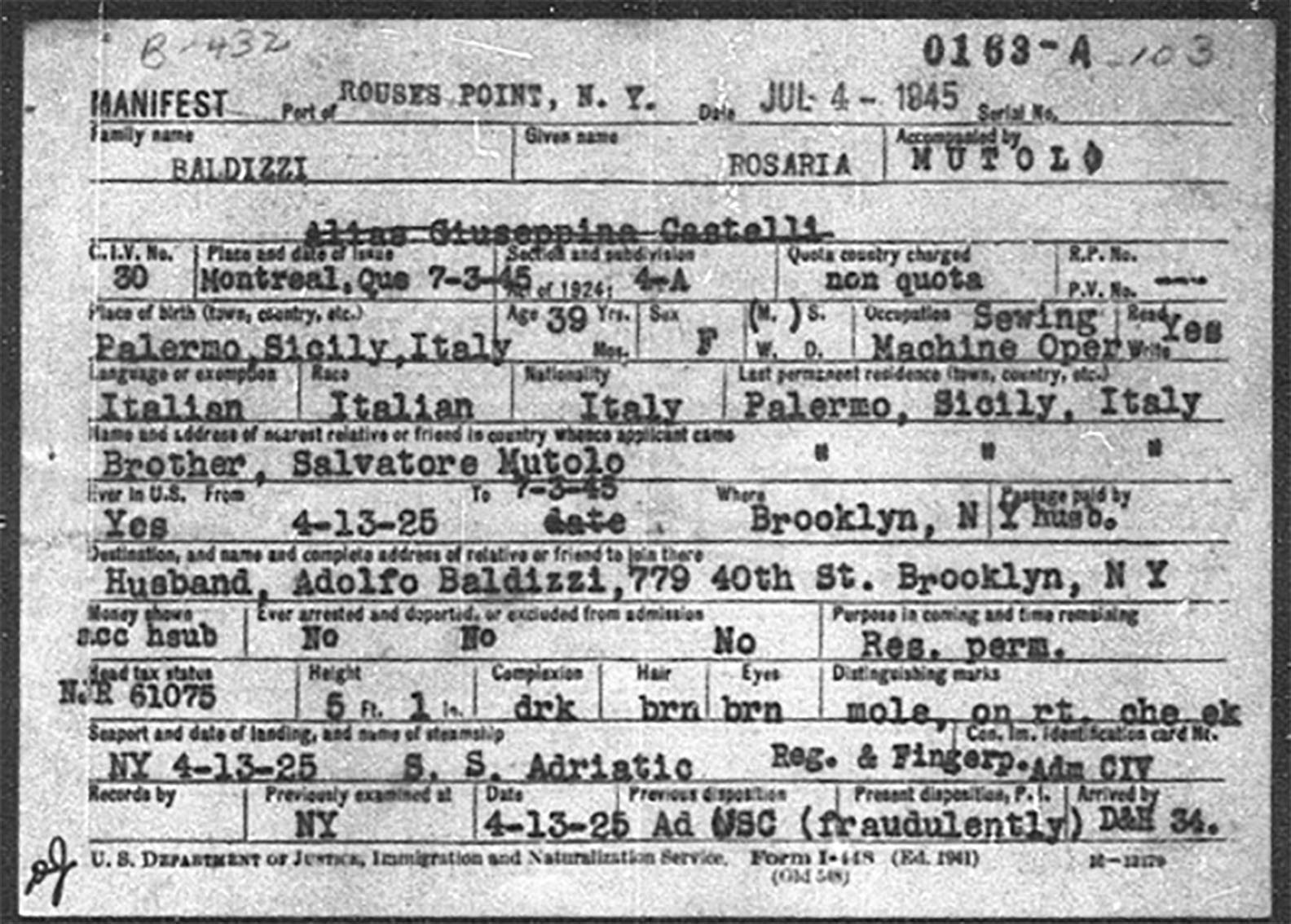

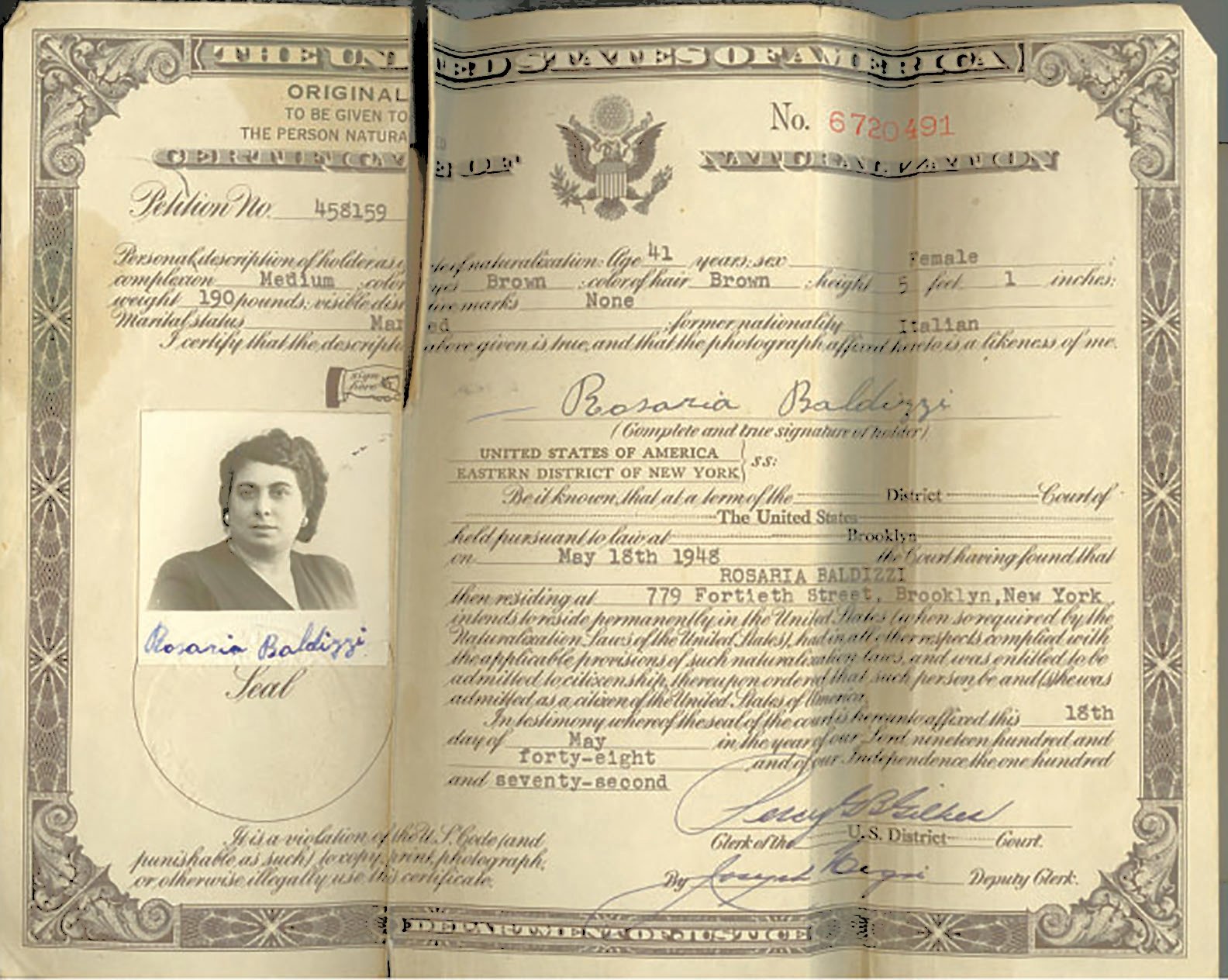

In order to be reunited with her husband in the United States, Rosaria Baldizzi had to circumvent the quota restrictions established by the 1924 National Origins Act. She remained an Undocumented Immigrant from her arrival on April 13, 1925 to her reentry through Canada on July 4, 1945. Josephine recalled this being a vulnerable issue for her mom- not that it stopped her from bringing the issue up.

“We used to tease her. We said, “Mom, you’re going to be back in Italy, and we’re going to be here.” And she’d say, “Don’t. Don’t talk like that.”

As she got older, Josephine curiosity replaced her devilry, and she became more serious about her mother’s immigration process. From an interview conducted in June 1993, Josephine remembers:

“They were illegal. And then what happened was, I says, “How could you do such a thing?” you know? “How could you?” She was 16 or 17 years old. You know, no more than 18, because when I was born, she was 20 years old. She already was here at 19, so… but she was saying, “I didn’t know it was terribly wrong,” you know. “They made my papers” -these are the people that advised my father, probably. And they just went ahead with it. You know… That’s probably why they had no money either. Had to probably pay for all of that.”

This memory suggests that Rosaria’s immigration was brokered through a network of what today would be called human traffickers. Josephine intimates that her mom, being little more than a teenager, didn’t think to question the process. Yet in an interview from May of the same year, Josephine remembers the same story slightly differently:

Josephine Baldizzi: Somebody gave her a passport. I don’t know how they finagled that! When she told us, I says, “Wow! What if they caught you?” and she said, “Well in those days a lot of people… you know…” And then they told her “If you don’t have 25$ you can’t get off the ship.” So my father borrowed 25$ from somebody. Went down to the pier, and throws it up to her. And instead of her catching it, it went into the water. And then she says, “This is my life, boy!” (laughter) She had a miserable life.

Interviewer: Do you- Is that true?

Josephine Baldizzi: Nah, they didn’t have money.

There are consistencies between both recordings: the harsh reality of the family’s economic struggle is clear, as is Josephine’s disbelief at her mother’s risky immigration process. A key difference in the May recording is the suggestion that Rosaria, despite her youth, was well aware of what she was doing. Moreover, although Josephine doesn’t complete her mother’s sentence, there’s an implication that since ‘a lot of people’ found ways to circumnavigate the 1924 Immigration Law, Rosaria felt reconciled to do the same. The exclusionary quotas established by the 1924 made the process of immigrating to America an impossibility for hopeful arrivals departing from Italy, Russia, and the entirety of Asia. After 1924, married men who, immigrated before their wives, like Adolfo, were faced with the difficulties of being separated from their partners. Not content with the reality of exclusion, and being of no mind to return to Sicily, Adolfo found some ‘people’ and ‘finagled’ a way to be reunited with Rosaria. Entering the United States with another name as an American passport meant that Rosaria lived as an undocumented (or as Josephine remembered, “illegal”) immigrant on the Lower East Side and in Brooklyn for the next two decades. She raised two American born children, held a job, kept the house, socialized with friends and neighbors. Excluding her immigration status, she basically did everything that might be considered ‘normal’ for a mother. Yet because of her undocumented status, Rosaria lived with the constant threat of deportation… that is, until temporary reform came.

By 1935, thousands of people were living as undocumented immigrants in the United States. Like Rosaria, they lived in America for years, started families, and worked to support them. For all intents and purposes, they were wholly integrated as neighbors and community members. Locating and deporting these undocumented immigrants would be difficult and destabilizing. So, in response to a rising popular opposition to deportations the Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, expanded the 1933 Pre-Examination Procedure to undocumented immigrants. In effect, the Pre-Examination Procedure (which continued with two exceptions from 1933-1958) was a form of amnesty, granting undocumented immigrants to chance to become legalized American citizens. The procedure required the Undocumented Immigrant to voluntarily leave the country to Canada where they would report to the nearest American consul. There, they would apply for a permanent resident visa, and reenter the United States as a legal immigrant on the path to citizenship.

Though not naming it precisely, Josephine’s oral history indicates how Rosaria learned about the Pre-Examination Procedure, and that she was indeed a participant in the program:

So then what she had to do was register. Because it was 1939 or something. When did the war start? War broke out, and they’re telling you, “You got to straighten out your papers. You got to straighten out your papers.” The neighbors are Jewish people who were a little more educated about that. And they used to tell my mother, “You know Sadie you gotta do this, you gotta do that. They’re gonna send you back and your kids will be here.”

They went to Canada. And they got their papers straightened out, and reentered through there.