In the fall of 1965, Mrs. Wong arrived in New York City from Hong Kong. Her travel companions were her daughters: Yat Ping, seven years old at the time, and infant Alison. Burdened by luggage and travel-weary, this trio made their way to a one-bedroom apartment on 29 Allen Street on the Lower East Side, where they were reunited with Mr. Wong. Life was starting over in a strange new city. In 2015, when Museum researchers asked her what she thought of New York City as a newcomer, Mrs. Wong laughed and said, “I didn’t think. I didn’t know. All I know about is coming here and doing garment work.”

Behind The Scenes, Resident Feature

The Surprising Role of Fashion in the Life of Mrs. Wong

At the time of her arrival, the New York garment industry was thriving in Chinatown. Factories and jobs were plentiful- particularly for Chinese immigrant women. The notion that she would work in a garment shop likely took root while Mrs. Wong was still in Hong Kong – the strange city she’d started her life over in before departing for New York. Originally from Taishan in the Guangdong province of China, the Wong family moved to Hong Kong as part of a larger migration. From the late 1950s through the 1960s, people living on mainland China who were displaced, whose lives were destabilized, and who were fearful of being targeted by the Communist government fled to Hong Kong seeking temporary asylum. For many people, Hong Kong became a permanent home; for many others, it was a stopping point on a longer journey that ended somewhere far away, like the United States. Stories from people who had already made the trip came back to Hong Kong through family and friends.

By the 1960s, the Wong family already had roots in the United States. Mr. Wong’s sister was living in New York City, as was his father and brother. Each of them worked in garment-related industries. With his family and employment connections established in New York City, Mr. Wong bid a temporary farewell to his family in Hong Kong. Stories of the garment industry made their way back to Mrs. Wong in Hong Kong. So, by the time Mr. Wong ‘called for’ them to join him in New York City, Mrs. Wong probably had a fairly clear idea about the kind of work she was heading toward.

However, it would be several years before Mrs. Wong entered the garment factories. Between getting used to a new home in America, and raising her growing family, Mrs. Wong spent her first five years in New York City as a full-time parent and homemaker.

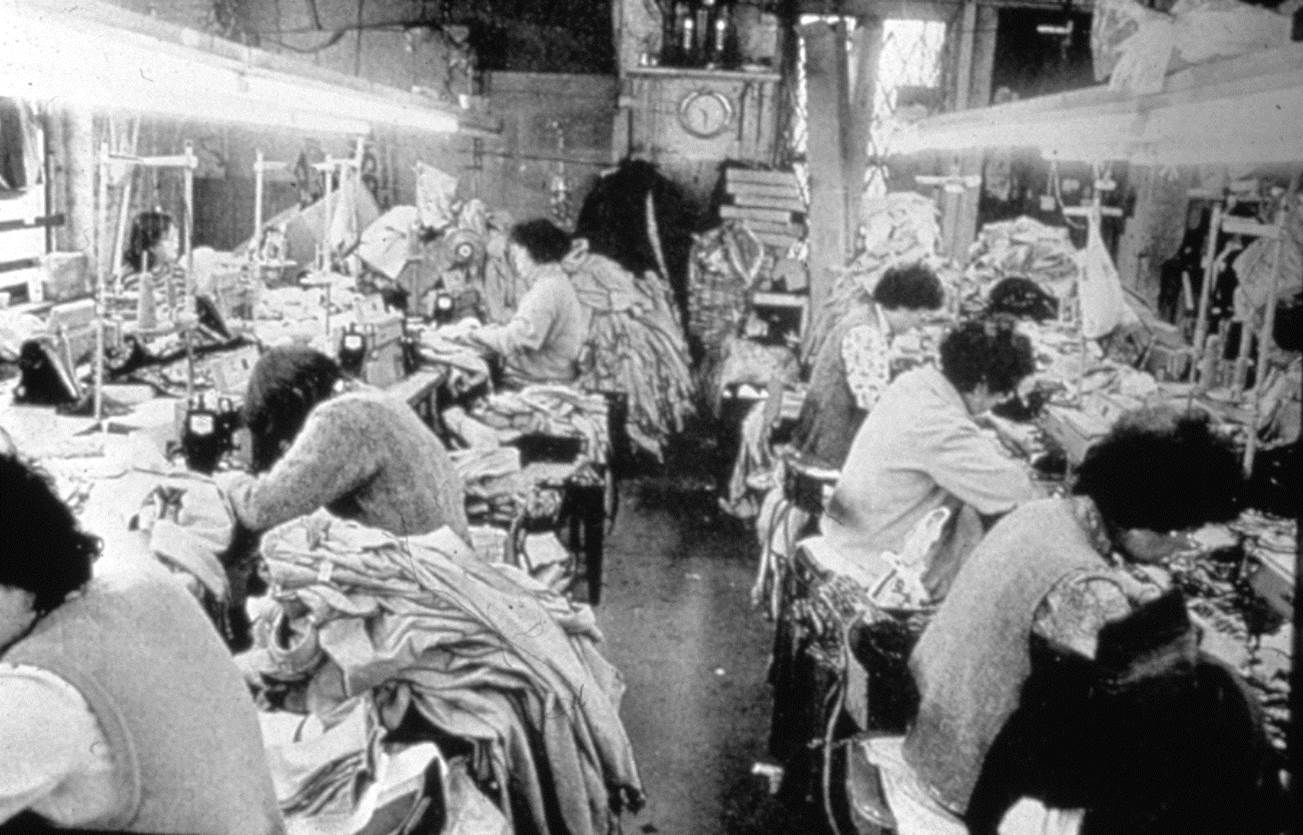

In 1968, the family moved out of their one-room apartment on Allen Street and into Apartment 12 at 81 Delancey (now the site of the Tenement Museum). In 1971, their fourth child, Kevin, was born. Later that year, as Kevin reached his first birthday, Mrs. Wong arranged to have his grandmother babysit him, and went to work in the garment factories as an entry-level laborer. Her memories speak to the prevailing ethic of ‘on-the-job’ training within the garment industry.

“When I first started, my paternal aunt came to teach me one time, but mostly I had to learn myself… Back then when I started sewing waistbands, there wasn’t much instruction. I watched other people doing it and I started to operate the machine. A lot of the work was really easy to learn. Sometimes it would break and I’d have to rethread the needle, so I just watched others do it and I did the same.”

Different machines were required to finish the garments, and mastery of each came with a small raise in pay. Over the years and through working in a dozen shops, Mrs. Wong mastered the numerous skills and machines, graduating to an elite class seamstress. She was now responsible for making samples, which involved making a complete garment to the specifications of the designer. Once approved, the piece was hung in the factory for other garment makers to copy. Mrs. Wong’s work was studied and replicated by the other workers, but she humbly denied having any active role in teaching her peers.

“I didn’t have to teach. No one teaches. They hang out a piece of garment and tell people to go look at it to see how to make it. Do what first, sew what first… follow how to make it from there.”

One thing Mrs. Wong did not deny was the role factory work played in her life. Drawn together through their work routines, immigrant experiences, and family life, Mrs. Wong and her fellow workers formed lasting friendships. In 1973, Mrs. Wong joined Local 23-25 of the garment workers union, which offered family insurance, holidays and paid time off, a sense of solidarity, and professional power.

As a member of Local 23-25, Mrs. Wong took part in union demonstrations large and small. She recalled joining 20,000 workers during the 1982 International Ladies Garment Workers Union Strike: “Being part of Local 23-35, you couldn’t not go.”

Local 23-25 worked hard to increase the visibility of their rank-and-file, producing and distributing paper hats to their members to wear in the strike. As she recalled, “the workers were all wearing Local 23-25 hats- baseball caps. They gave it to us for free. Some had a shirt… a t-shirt.” The Union was promoting a fashion of its own – one that visually represented and promoted solidarity.

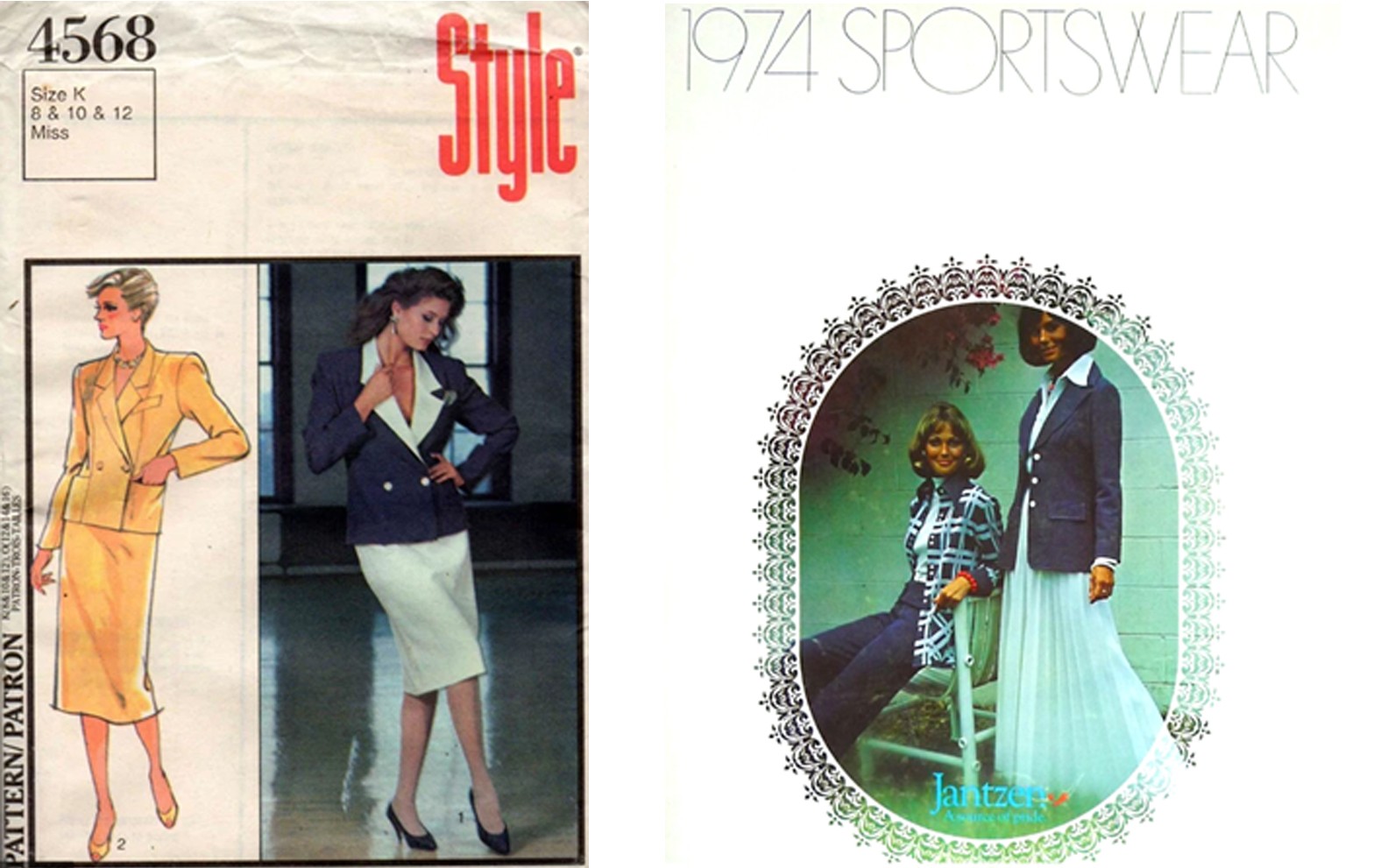

But union-branded style was not the only fashion Mrs. Wong adopted. The New York City garment industry’s success was fueled by expanding fashion trends for women. Beginning in the early 1970s, designers ramped up production of ready-to-wear clothing, to accommodate the large number of women entering the white-collar workforce. In the Fashion world, the blanket term for this style of clothing is “sportswear.” May Chen, a garment worker, labor organizer and advocate, and former Vice President for Local 23-25, offered a detailed description of sportswear during a 2016 interview with Museum researchers:

“Sportswear was kind of the set of mix and match garments, like a jacket and a skirt and pants. Maybe a dress that would go under the jacket. You know, there are four of five pieces that would kind of match and give a career woman the kind of things that she could choose to wear to work every day.”

“Some of the women looked [at the work] as really just churning out their pieces and you know…making a living. But there’s a fair number of people who really liked making clothing. I mean, there’s kind of a creative aspect of it- and they liked buying clothing. They were all women, so they liked the whole idea…of creating something with their hands.”

Brand names including Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, and Anne Klein, sent their designs to Chinatown garment factories for mass production. As fabricators, the garment workers had their own preview of the next season’s trends. The exposure to, and fabrication of, American fashion was exciting for many immigrant women.

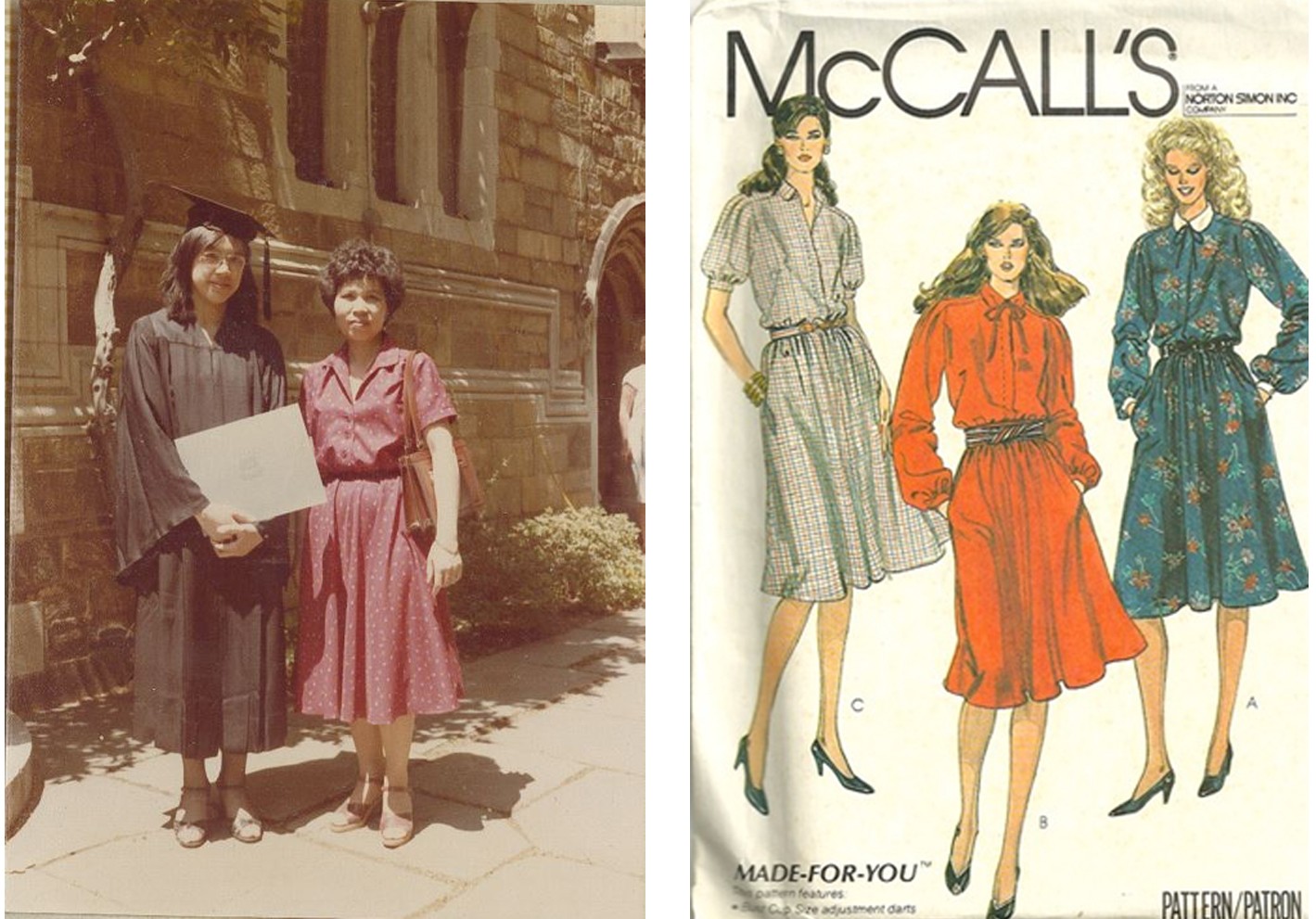

Many of the workers, having developed a comprehensive understanding of how to make and size a complete garment, made custom versions for themselves. Mrs. Wong recalls making tailored designer dresses for her daughter, Yat Ping, when she entered the workforce. “A lot of times, my oldest daughter works at an office. I would buy the cloth and sew it in size seven for her. Yeah. My daughter’s friend has also asked me to sew one for her.”

The dresses Mrs. Wong made for Yat Ping speak to a larger American stry: the story of parents working in factories to support their families, the story of building a personal community through common work, and the story of finding political power through collective action. It’s also the story of a mother filled with tenderness, pride and hope for her daughter as she begins her own working career. It’s the story of a daughter achieving the next level of employment and opportunity because of her mother’s factory work. It’s a story so common that it almost disappears. Mrs. Wong herself downplays her experience: “I went to work, then I came home. It wasn’t anything special.”

Understated and matter-of-fact, Mrs. Wong’s humility might overshadow her achievements in America. Inseparable from her American story is the story of her immigration. When asked what she thought New York would be like, she replied, “There isn’t much to talk about. You come here to work.” Mrs. Wong expected to work in a New York garment factory, but the notion that she would graduate to become an elite-class worker who would earn the responsibility of making samples for American designer brands, or that she would find joy in the work (despite the hazards of factory labor), or that she would join her sisters and brothers of Local 23-25 in street demonstrations, or that her job could become a source of creativity and collective power, might have been beyond her earlier imagination.

In 1965, Mrs. Wong boarded an airplane, stepping boldly into a new life in New York City. In 1971 she entered the garment industry where she remained until 2001, when New York’s Chinatown garment industry all but imploded. In 1973 she joined Local 23-25, and in the same year, she became a citizen of the United States. Details from the memory of her Naturalization Ceremony reveal the how tightly woven Mrs. Wong’s factory work was to her American story:

“The letter that told me to go to the swearing-in said I had to wear a dress. I made the dress myself. I went to the garment factory and made myself a dress. Ha-ha! I don’t remember [the color] any more. It was very cute, so I remember that.”

In the fashion world, styles change with each passing season. Specific details tend to get forgotten over time. Our memories function the same way; as the years pass, the smaller details become more difficult to recall. After 46 years, Mrs. Wong could no longer recall the color of the dress, but remembered that she made the dress herself and felt good wearing it. The dress symbolized her creativity and pride, a representation of everything she learned in America. Dressed in a cutting-edge style, custom-tailored, literally self-made (not to mention very cute), Mrs. Wong repeated the solemn oath of citizenship, and thereafter, went back to work. Just another day. Nothing special and at once extraordinary.