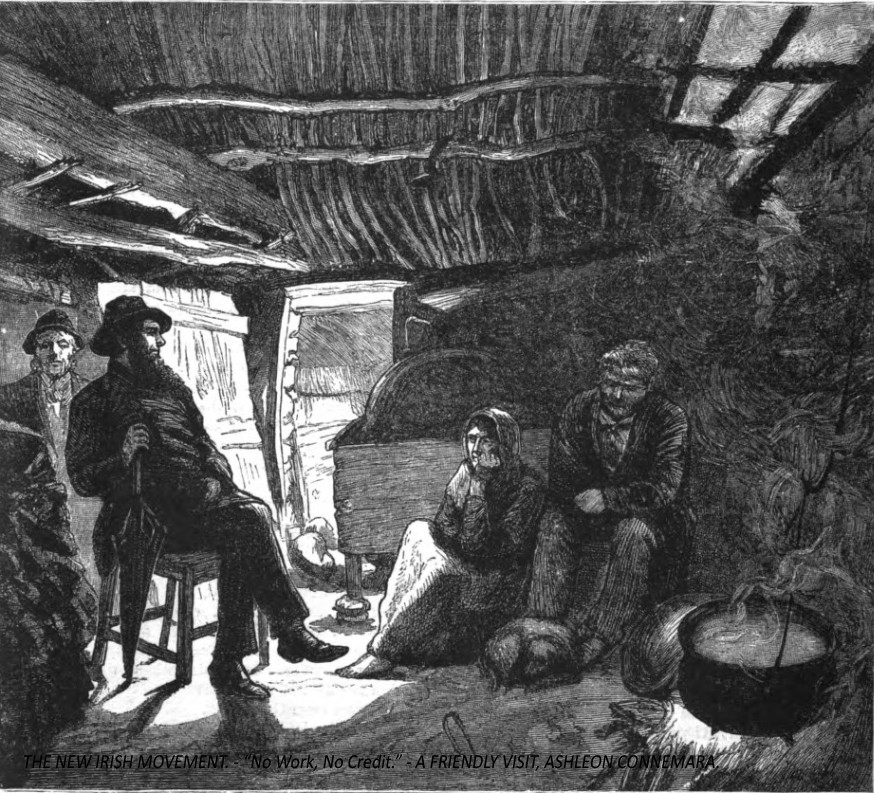

But on the morning of April 22, 1869, there was one less person at the Moore table. Agnes, their infant daughter, had died the previous day. She was nearly six months old. Awake early, Bridget would complete her crossing from bedroom to kitchen along cold pine floorboards to stoke the fire and warm the apartment. In this quiet time, while her family was perhaps still asleep, Bridget could reflect and mourn over the losses in her life. As she rebuilt the fire, was she conjuring the memory of her family gathered around a hearth in Ireland – the smell of turf, the warmth of the fire, and the sense of hope it offered? And as the room began to heat up, was Bridget able to feel comforted and consoled?

There is no way to accurately answer these questions, but there is tremendous importance in asking them, for they uncover an underlying sense of humanity that draws us closer to Bridget Moore- her joy, her hopes, her pain. The stove- an essential object of Bridget’s daily life- sits in silence waiting for our questions. A more personal portrait emerges out of this informed speculation, and by contemplating the myriad ways Bridget interacted with the stove, we establish an empathy powerful enough to cut across the generations.

1 https://cottageology.com/irish-cottage-history/

2 http://archives.evergreen.edu/webpages/curricular/2006-2007/ireland0607/ireland/eyewitness-accounts-of-the-famine/index.html Thomas Colley Grattan, 1847

3 Historical Archaeology, Vol 33 No1 Confronting Class (1999), Go gCuire Dia Rath Agus Blath Ort (God Grant That You Prosper and Flourish): Social and Economic Mobility among the Irish in Nineteenth-Century New York City. Griggs, Heather J. P90

4 http://archives.evergreen.edu/webpages/curricular/2006-2007/ireland0607/ireland/eyewitness-accounts-of-the-famine/index.html The Times, quoted in The Nation, May 1860

5 http://archives.evergreen.edu/webpages/curricular/2006-2007/ireland0607/ireland/eyewitness-accounts-of-the-famine/index.html (William Trench, land agent in County Kerry)

6http://archives.evergreen.edu/webpages/curricular/2006-2007/ireland0607/ireland/eyewitness-accounts-of-the-famine/index.html (William Trench, land agent in County Kerry)

7 http://archives.evergreen.edu/webpages/curricular/2006-2007/ireland0607/ireland/eyewitness-accounts-of-the-famine/index.html (Father White, Ballinasloe, Co. Galway, 1847)

8http://archives.evergreen.edu/webpages/curricular/2006-2007/ireland0607/ireland/eyewitness-accounts-of-the-famine/index.html (Monsieur Soyer The Lancet, April 1847)

9 The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, Vol 41, The Food Issue(2018), Recipe Collecting, Embodied Imagination, and transatlantic Connections in an Irish Emigrant’s Cooking,Wack, Mary F. p.112

10 Reforming food in Post-Famine Ireland: Medicine, Science, and Improvement 1845-1922. Miller, Ian 2014

11 The Art of Irish Cooking, Sheridan, Monica,1965 p.xvi

12 At Home With the Range: The American Cooking Stove, 1865-1920, Ellis, Phyllis Minerva, 1985 p28

13 IBID Ellis p21

14 IBID Ellis p28

15 Early American Cookery: The Good Housekeeper, Hale, Sarah Josepha 1841, p26