Amelia Louisa Carolina Dietmann, who went by Caroline, moved from the city of Bielefeld, Germany to New York when she was a teenager, just 14 years old. She lived on Spring Street, about 10 minutes away from the German neighborhood of Kleindeutschland, today’s Lower East Side.

John Schneider immigrated from the small town of Burgpreppach, in Bavaria, at 12 years old. One of six siblings, he came from a musical family and worked as a musician and shoemaker, even serving in a musical regiment of the Union Army during the Civil War.

While we don’t know how John Schneider met Caroline Dietmann, their marriage certificate documents their wedding in January of 1863 at St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church, the same church where landlord Lucas Glockner married his first wife Catherina.

Eight months after their wedding, on November 12th, 1864, John and Caroline open a saloon at 97 Orchard Street. They would run this business together for 22 years.

Together, John and Caroline created an environment that reflected their personal preferences and neighborhood connections, met the needs of their patrons, and echoed elements of their history as German Americans.

Photo: Reconstruction of Schneiders Lager Bier Saloon.

While John represented the front of the house, the daily operations of the saloon required Caroline’s behind-the-scenes maintenance. In every way, she had as much responsibility as John for making the saloon a thriving small business. While her touch was everywhere, from the clean towels and the swept floors, to the emptied ash from the pot belly stove –nowhere was it more felt than the lunch table offerings.

Caroline would have established close ties to neighborhood vendors to procure the best prices and choice produce for the ‘free lunch’ offered at the saloon. Her customers likely came to crave her cooking, and made the saloon unique among many similar establishments. Yet this work took its toll, and she would have toiled endlessly between shopping, cooking, and cleaning, spending many hours in front of a coal burning stove and in the rear yard. This invariably led to long periods of exposure to coal soot and potentially unsanitary conditions.

Photo: Reconstruction of Schneider family kitchen.

Through this work, the Schneider’s maintained their relationship and eventually grew their family. In 1877, the family grew to include a baby boy named Harry.

Tuberculosis Strikes

It was shortly before or soon after Harry’s birth that Caroline appears to have fallen ill with pulmonary tuberculosis. Her husband, John, likely became ill with the same.

Caroline would soon be too tired to fulfil her role as mother to infant Harry -let alone complete the nearly 24-hour-a-day responsibility of maintaining the saloon. How would Caroline spend her fading energy? How did she balance being a mom and being the invisible hand that kept the saloon a clean and vital space? As her symptoms became more acute, the signs of John’s infection may have just started. It would have become harder to rise early in the morning and serve the regular patrons, and the various clubs that John was a member of may have concluded earlier in the evening. Caroline may have had to swallow her pride and accept a saloon that was a little less spotless. Still a part of the fabric of the saloon, the regular patrons and club members would have grown accustomed to hearing her persistent rasping cough and seeing her less.

We might imagine during Caroline’s illness, customers and friends offering words of comfort. A common German proverb, “Unkraut vergeht nicht,” which translates to “Weeds don’t vanish,” is spoken when someone perseveres despite challenges. Here, the word “weed” is meant positively, noting the importance of plants and “weeds” as food and medicine in Europe. Perhaps neighbors and friends offer to help out with tasks in the saloon, or running other errands for the ailing Caroline.

Where to Turn for Treatment?

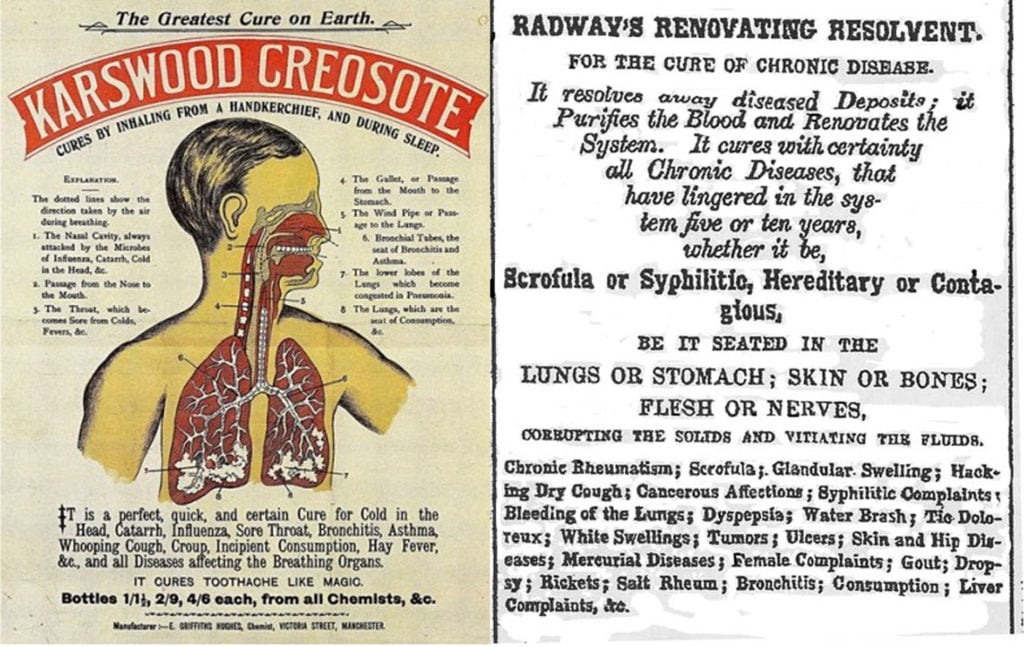

Their bodies ravaged by a slowly worsening tubercular infection, John and Caroline had few places to turn for medical care. Despite the lack of curative treatment for tuberculosis, a visiting physician may have prescribed patent medicines, ubiquitous in the 19th century as means of addressing a host of illnesses.

Photo: “The Interior Dark Bedroom is Where Tuberculosis Spreads”c. 1900. Jacob Riis. Credit: Museum of the City of New York

Photo (left): Advertisement for Radway’s Renovating Resolvent patent medicine. From the Irish American, April 1869.

Photo (right): Advertisement for Karswood Creosote. 1898.

These patent medicines claimed to cure any ailment a person might suffer from, but they did little more than temporarily alleviate some of the symptoms –principally because they often contained high levels of narcotics or alcohol. There being no oversight, manufacturers and purveyors were not required to list a medicine’s ingredients or substantiate the claims made to its effects.

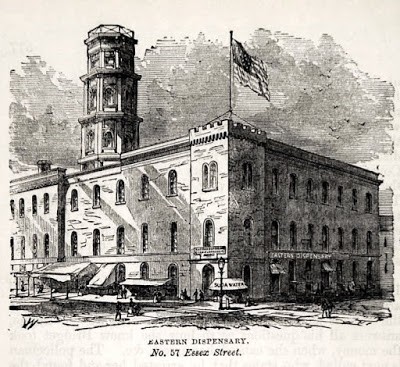

Photo: Eastern Dispensary, No. 57 Essex Street. Report of the Eastern Dispensary, 1872. Source Unknown.

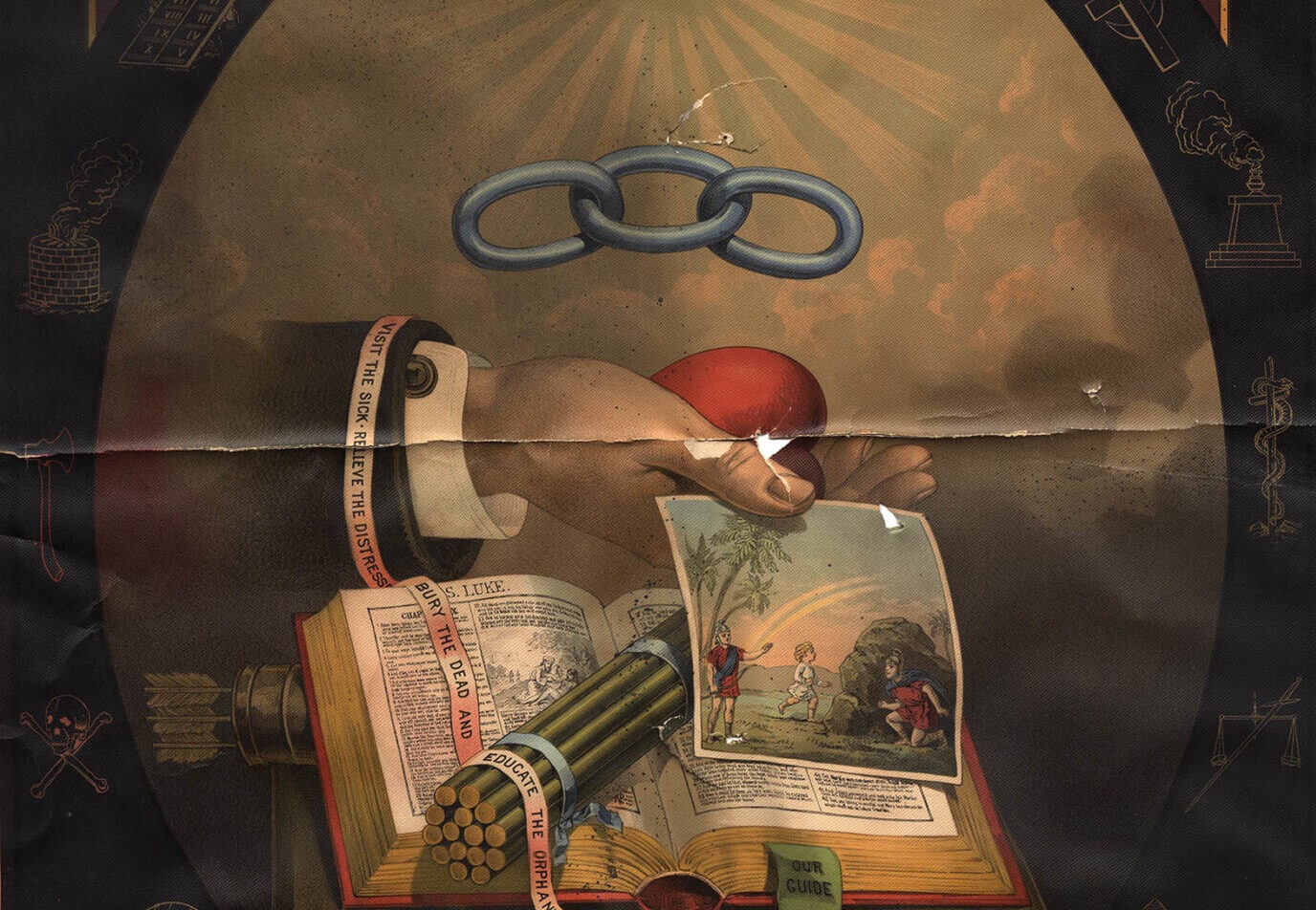

As they became increasingly ill the Schneiders may also have turned to fraternal organizations and vereine (clubs) to which they belonged. The decades immediately following the Civil War mark the golden age for membership in fraternal societies and voluntary organizations. In the absence of any official or government entity devoted to social welfare, immigrant and migrant communities joined together for mutual support and benefit. Immigrants from the German States brought with them a Verein culture, so for them native and international fraternal societies were a natural fit.

Announcements from the Staats Zeitung establish John as a member of both the United Order of Red Men and the International Order of Odd Fellows. Every month a member paid dues. In turn, when unemployment, sickness, or death struck, the Verein’s funds were apportioned to the member in need. Certainly, when Caroline took ill, John would have called on his fraternal network.

Photo: International Order of Odd Fellows Chromolithograph. Late 19th Century. Collection of Keweenaw National Historic Site.

Death

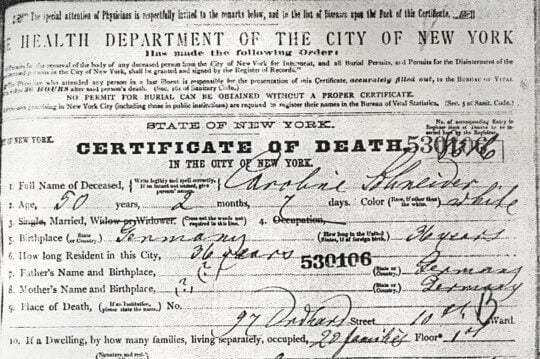

Caroline died of tuberculosis in 1885 at the age of 50. Her absence from the saloon community, the market, the rear yard, and from John’s life would have been acutely felt. It is impossible to know how advanced John’s tuberculosis was at the time of Caroline’s death.

Photo: Death Certificate for Caroline Schneider, June 6, 1885. Collection of New York Municipal Archives

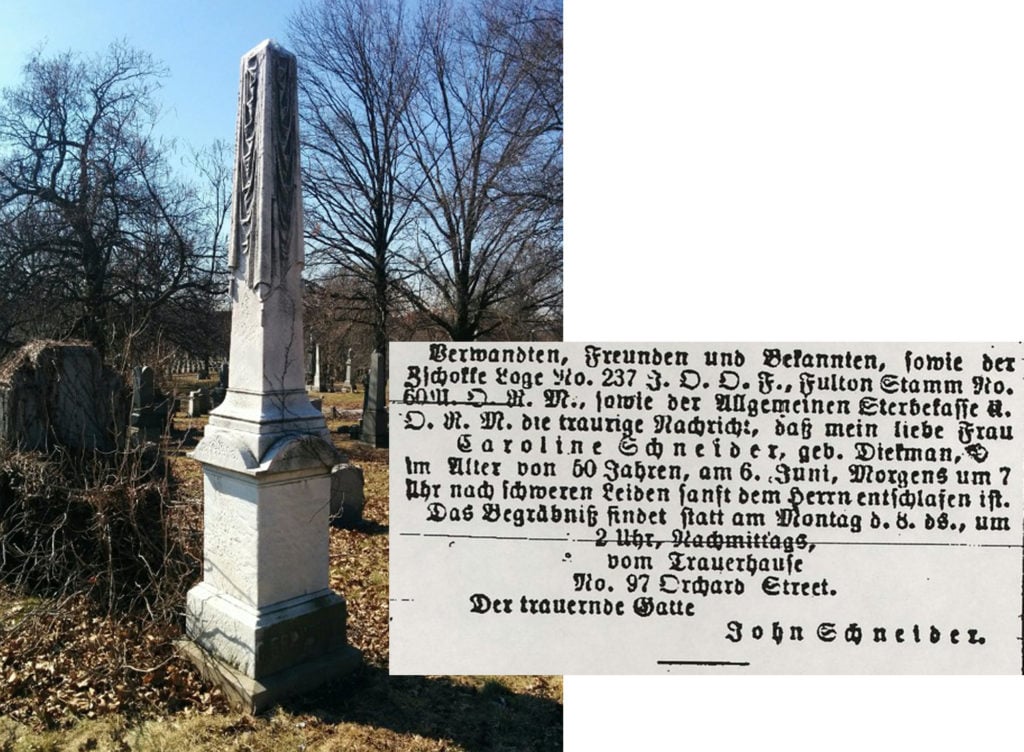

Photo (left): Photograph of Caroline Schneider’s burial monument at Lutheran All Faiths Cemetery in Middle Village Queens, New York. 2006. Photo by Joan Koster Morales.

Photo (right): German language obituary for Caroline Schneider placed by her widower, John Schneider, in the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung on June 7, 1885. Collection of New York Public Library.

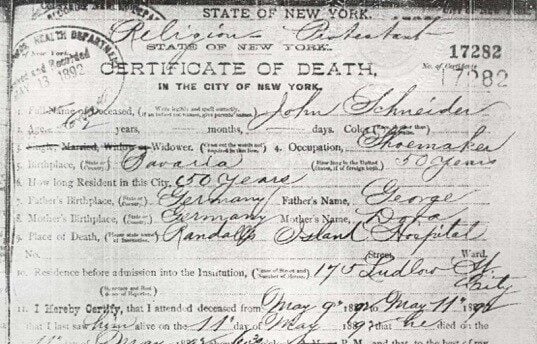

While he did his best to maintain his old saloon in the basement at 97 Orchard Street, he soon closed shop and relocated across the street to 98 Orchard Street in 1886. His own failing health, the stress of being a single parent, and an out-migrating German community are all possible contributing factors leading John to ultimately conclude his career as a saloon keeper in 1890. John and Harry had moved several blocks away to 175 Ludlow Street and on May 12, 1892 John died of tuberculosis.

He did not die at home. John died at the Randall’s Island Hospital, a place reserved for those with little or no money at all. As far as any record indicates, no one posted an obituary or had a wake for him.

Photo: Death Certificate for John Schneider, May 11, 1892. Collection of New York Municipal Archives.

Tuberculosis claimed the lives of John and Caroline. There is nothing ‘special’ or ‘extraordinary’ about their passing, as death from tuberculosis was a common part of life before the 1880’s–perhaps even more reason to commemorate them and their lives, and the context in which they lived and died.

Perhaps the biggest tragedy for the Schneiders and all who died from tuberculosis in the 1880’s is their proximity to Herman Koch’s breakthrough research in microbiology.

Next, we explore tuberculosis, also known as “the White Plague.” We’ll go deeper into what was the deadliest disease affecting the US and Europe from the 1800’s to the early 1900’s.