José ‘Bennie’ Beniquez Santiago and Crispín Ramos shared a residence at 81 Delancey (aka 103 Orchard Street) for over two decades, yet telling their story is particularly challenging. We did not get to speak to them, we have no photographs of either of them, and we don’t have many documents to chart their experience. A gay couple who died in the early 1990s, likely from AIDS-related complications, Bennie and Crispin deserve to be known.

We tell their story to honor their lives and the lives of other people whose stories are too often forgotten or silenced in history.

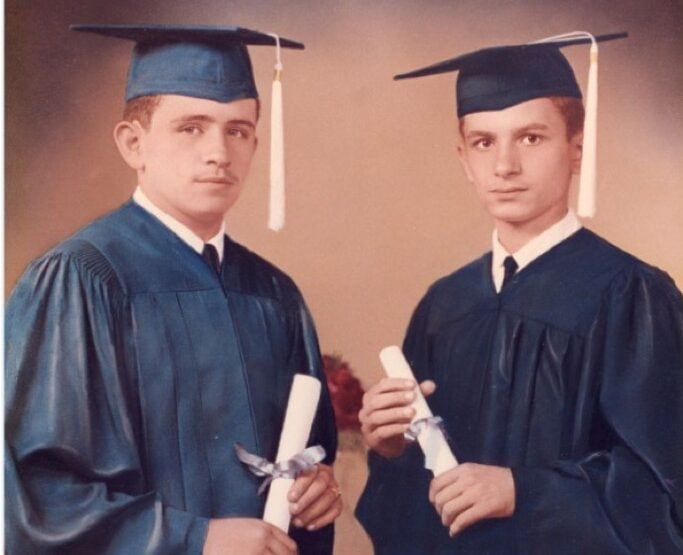

The museum learned about Bennie and Crispín’s experiences from memories of their neighbors, José and Andy Velez, brothers who were each served as superintendent of the 103 Orchard Street at different times. The Velez brothers knew Bennie and Crispín both as their building super and as their friends.

Photo: Jose and Andy Velez High School graduation photograph, 1968. Collection of the Tenement Museum

We supplement what we heard from their neighbors with sources from activist community groups and oral histories from Puerto Ricans on the Lower East who lived through the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s.

Memories from Neighbors

Members of the Saez Velez family knew these two men, and offered their perspective on Bennie and Crispín’s life together. José Velez recalled that he first met Bennie and Crispín in the early 1960s through a mutual friend, when they were all neighbors residing in the tenement at 282 Broome Street. They would go out —a few friends, José, plus Bennie and Crispín —to Coney Island on weekends and to the Delancey Theater for their Mexican comedies on Wednesday nights. Bennie and Crispín told José they’d like to move to 81 Delancey Street, which was considered a ‘better area’ and building. When a long-time tenant who ran a dentist office and laboratory on the second floor moved out, José, then the super, invited them to rent the apartment.

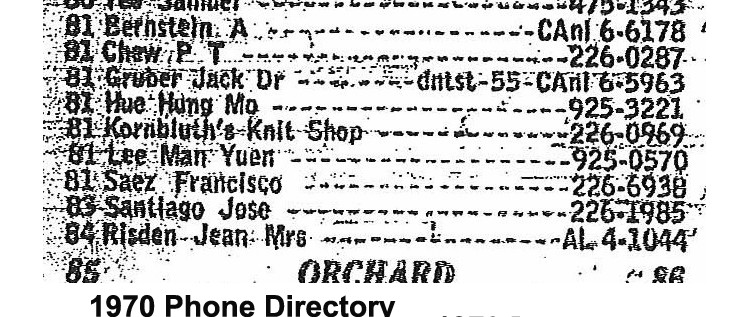

In phone book records, a “José Santiago” lived at 81 Delancey in the 1970s and a “Beniquez Santiago Jose” lived there in the 1980s. The two different versions of Bennie’s name can be attributed to Puerto Rican naming conventions, where one assumes the surnames of both parents. The Velez brothers along with many of their neighbors at 81 Delancey knew him as Bennie —maybe shortening “Beniquez” to Bennie as a nickname.

Photo: Tax photograph of 103 Orchard Street, c. 1980s. Collection of New York Municipal Archives.

Photo: Telephone book listing for 103 Orchard Street showing “Santiago, Jose” residing in the building in 1970. Collection of New York Public Library.

Apart from the phone books and the oral histories collected from the Velez Brothers and neighbors who knew Bennie and Crispín, there is limited available primary source material to define their lives. Public records, like the census and or a death record, have time-based or privacy restrictions and remain unavailable. Through collected oral histories, the contours of Bennie and Crispín’s life and partnership in 81 Delancey come vaguely into focus.

“They Used to Keep it Spotless”

José recalled both Bennie and Crispín were tall, “mulatto people” in their late 30s, from Puerto Rico. Their apartment was “nice and cozy. They used to keep it spotless.”

Andy Velez, José’s brother, remembered that Bennie was skinny, well-groomed, with short hair. Bennie worked at the post office across from Madison Square Garden but was not a delivery man, so he may have worked processing mail. Crispín was stocky, with “rich, black hair.” He worked as a seamster in a garment factory. He used to sew in his apartment and made things for his home.

One year, as Andy recollected, Crispín made a ‘sky blue’ jumpsuit (complete with little straps) for Andy’s wife, Jennie, on her birthday.

Photo: Photograph of Andy and Jennie Velez on their wedding day, 1969. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

They were “very social” and would often go out together, and friends would come to visit them. The couple was well integrated into the social fabric of the building, particularly among the Puerto Rican residents. They received regular invitations to socialize on Sundays when many Puerto Rican Lower East Siders opened their apartments to family, friends, and neighbors to share food and music. They would also come up to the Saez Velez apartment for conversation and coffee. Ramonita Saez knew them well. These memories reflect an intimate and sustained friendship.

Unspoken Expectations

José recalled that he and other Puerto Rican tenants of 81 Delancey knew Bennie and Crispín as a gay couple. In his estimation, “They had nothing against it.” This memory suggests that for the most part, as Puerto Rican gay men living on the Lower East Side during the 1970s and 1980s, Benny and Crispín were accepted, with limited isolation, ostracism, or visible discrimination. However, it is likely that there was an unspoken expectation that they be discreet about their gay relationship.

The Impact of Silence

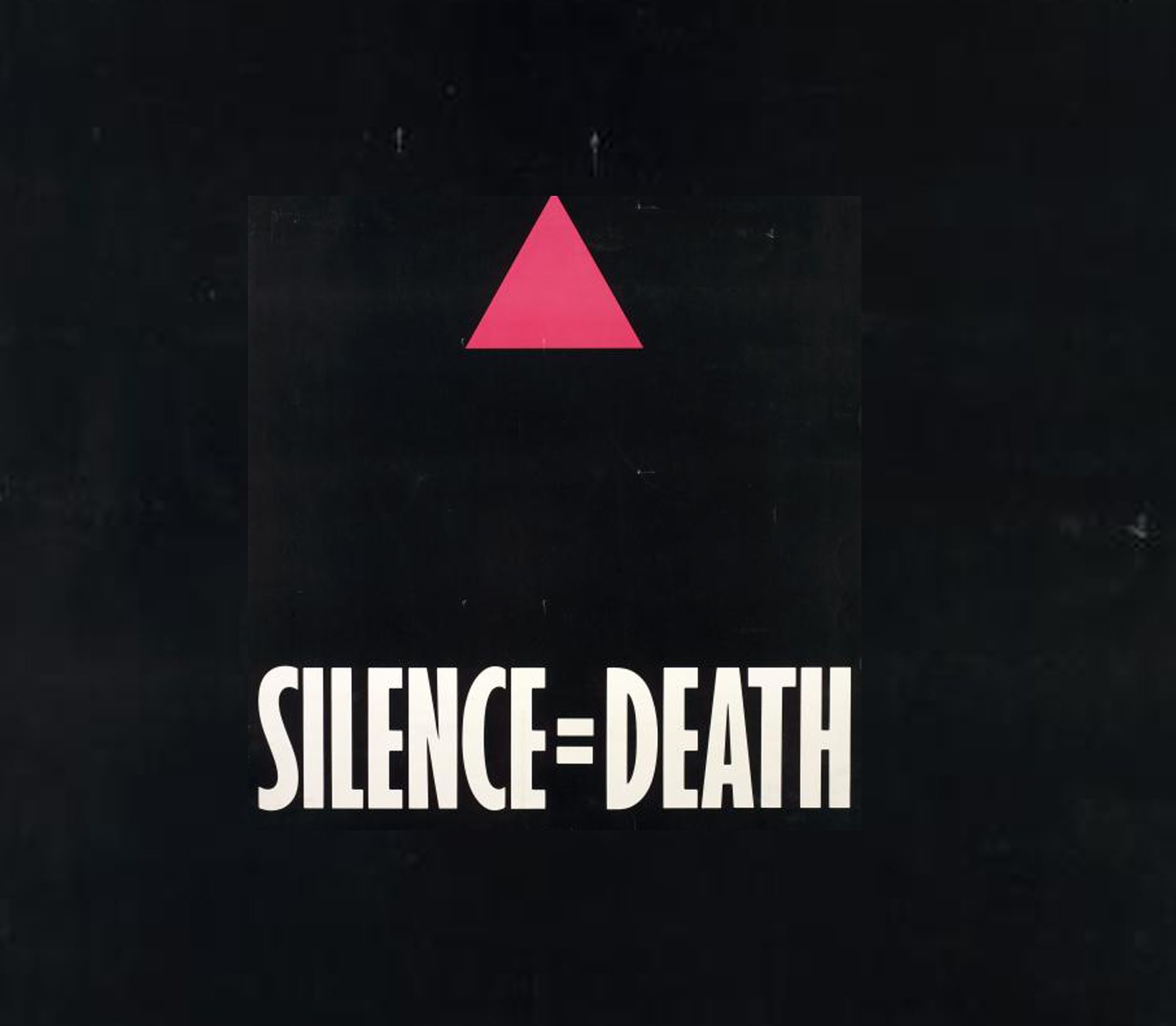

Secrecy and silence are common threads in gay history across time, as the structure of US society privileged heterosexuality and openly discriminated against gay culture and individuals. A public gay identity could lead to destabilized family ties, isolation, physical and emotional abuse and bullying, unemployment, housing discrimination, and living with the persistent threat of a biased, intolerant society’s disapproval.

Photo: “Silence = Death” poster, 1987. This image was used by activist organization ACT-UP battle against the epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Collection of New York Public Library.

However, geography, race, and class were important contributing factors in establishing safe spaces for the open expressions of gay culture. In New York, this meant the predominantly white middle-class gay couples in ‘the Village’ could hold hands, embrace and kiss while in public. On the Lower East Side, where the community of gay men was largely Latino or Hispanic, these romantic expressions were “not exposed” and “quiet,” not as public as in other neighborhoods.

In most cases, openly gay Puerto Rican men were extremely vulnerable to homophobia and ostracization from fellow Puerto Ricans. Yet the New York Puerto Rican migrant community gave rise to a distinct queer subculture, known as Boricuas, who celebrated their queer identity through irreverent, iconoclastic, unapologetic drag performance.

Photo: “Boricua” photograph, date and source unknown.

For the Puerto Ricans of the Lower East Side, certain expressions of gay identity could be accepted under specific conditions. Boricuas, as well as the flamboyant gay men who worked in area beauty salons were accepted and celebrated -at least as long as they were in the salons.

The 1960s and early 1970s were expansive decades for social justice, Civil Rights and the Black Freedom Movement, and the struggle for equality. Members of the gay community mobilized against societal condemnation, structural discrimination, and invisibility. The highly visible Boricuas represented courage and pride, and the Queer Latinos of New York City took an active role in the struggle for gay liberation.

By the second half of the 1970s, the fight for Civil Rights continued at a slower rate, and less in the public eye, as the nation turned its attention to rising fears of urban decay. Many people in the nation returned, as seen over 100 years before, to negative perceptions of urban spaces –likening them to disease, as ‘infected’ with criminality, corruption, poverty, and immorality- societal illnesses dangerous to the ‘general public’ (a coded term representing heterosexual white middle-class and upper-class values).

It is in this period, as the nation reflexively drew inward from a military failure in Vietnam and the expanded liberalism of the 60s, the first cases of HIV were reported. In June 1981, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that between October 1980 and May 1981 five young men had been diagnosed with a rare lung infection called pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP).

One month later the CDC reported that in the prior thirty months, 26 cases of an unusual malignancy, Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS), had been diagnosed in New York City and California. These men died of rare diseases enabled by a severely compromised immune system. The one apparent constant among these first reported cases was their sexual orientation –all were gay men.

In a climate that was swinging back toward the moralism of the 1850s, the ‘general public’ interpreted HIV/AIDS as a form of divine punishment. Media reports initially referred to AIDS as Gay-Related Immune Disease (GRID) cementing the association with the gay community. In these early years of the HIV/AIDS crisis, fearful conjecture spread faster than scientific studies, giving rise to ignorance-inspired panic and widespread anti-gay discrimination.

For the people that maintained a life of secrecy, the infection itself became a form of ‘outing’ their identity. Stigma was overwhelming, especially in the early and mid-1980s, when misinformation leads to widespread fear that HIV could be transmitted by casual physical or respiratory contact. According to one report, “People With AIDS (PWA) —or people who were merely thought to be infected with HIV —were shunned, evicted from their homes, fired from their jobs, and kept out of their schools.” The impact on the individual with HIV/AIDS was dehumanizing, discriminatory, and isolating.

Getting Sick and Getting Treated

During the turbulent and volatile first decade of the crisis, neighbors believed that Bennie and Crispin became sick due to complications from AIDS. Maintaining their life of discretion would become impossible for Bennie and Crispin after they appeared to become sick with HIV/AIDS related symptoms. Neighbors and friends do not recall learning precisely when and how the couple were exposed to the virus, nor do they mention Bennie and Crispin’s feelings about what it meant to be sick with complications from AIDS.

Their illness and death are a part of this larger—and rarely discussed–Lower East Side history. Because their relationship was effectively silenced, the facts and trajectory of their illness is unknown. Neither Jose nor Andy spoke to their friends about HIV/AIDS.

Andy recalled:

“I respected their privacy… In those days you didn’t have no medication, no nothing. You got it, you’re gone. People stopped visiting. You could “smell the sickness” in the area. Nobody knew how the disease was spread. The apartment was dirty; they may have been too sick to clean it. Bennie and Crispin died in the hospital, not in the apartment. It might have been Bellevue Hospital.”

-Andy Velez

This portion of Andy’s oral history describes how Bennie and Crispín struggled to maintain the basic functions of their life. In this, they were not alone. While the first-hand perspectives of Bennie and Crispín are absent from this narrative, and Andy’s memory does not include mention of their feelings, oral history archives collected during the early decade of the pandemic describes what it was like to suffer through HIV/AIDS.

Angel Rodriguez-Diaz migrated from Puerto Rico in 1978 to pursue a Masters in Fine Arts at New York University. He became romantically involved with Manuel Ramos Otero, an influential, openly gay Puerto Rican writer. Sometime in the mid-1980s, Angel was diagnosed with AIDS.

“Nobody knew. It wasn’t even called AIDS. They didn’t even know what was going on and because people died on some kind of cirrhosis of the liver… we kept hearing somebody else got sick, da da da. And it was – everybody was scared. The AIDS epidemic was rampant and it was like hundreds already- they didn’t know what was going on- they didn’t know how to treat it. The only thing they knew was the symptoms, and there was one thing that was really debilitating, was horrible- pneumonia was one and diarrhea- waste we call it now- waste.”

-Angel Rodriguez-Diaz

Robert Vazquez-Pacheco shared his feelings about how his partner was treated at a hospital:

“I was angry. I was angry about the fact that my lover had died. I went through those early days of the orderly [at New York Hospital] leaving the food tray- the couple of times that he was hospitalized- on the floor outside his room, or the nurse putting on the space suit to come in to talk to him…I was the one that would go out and make a scene in the hallway: “Why are you putting the food on the floor?” So I remember all of that, after he died sort of carrying all of that anger and frustration with me and wanting to do something much more active or proactive.”

– Robert Vazquez-Pacheco

Informed by misleading and confusing media, fear of contagion and deeply engrained homophobia Bennie and Crispín’s neighbors and friends turned away at a time when they needed support and understanding.

We don’t know whether Bennie and Crispín sought any treatment, but they seem to have left their apartment building as the illness progressed.

More Questions than Answers

Crispín Ramos may have left the apartment at 81 Delancey in the mid-80s, as José Velez remembers. His brother Andy recalls differently, that Crispín stayed into the early years of the 1990s. The details of his death remain unknown. José “Bennie” Beniquez Santiago may have died in 1992. The Social Security Death Index lists a 37-year-old José Santiago with a death date of September 30, 1992, last residence was in the zip code 10002 which is the same as the 81 Delancey address. Presently the Museum has no documentation to support the claims made by their friends and neighbors, that Bennie died from complications due to HIV/AIDS. Bennie and Crispín’s lives and deaths are profoundly incomplete stories with more questions than answers.

Like so many of the People with AIDS who died at the beginning of the pandemic, a full account of their story may never be known.