What histories do the city’s landscape hide from us?

When investigated closely, this single-family row house at 143 Allen Street (see above) reveals centuries-old experiences of Black New Yorkers, from before New York existed.

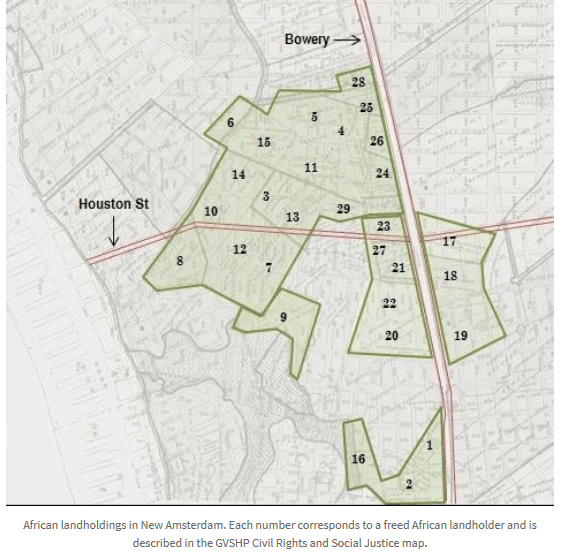

This land formed part of what was known in the mid-17th Century as ‘Land of the Blacks,’ a settlement of farms and homes owned by Black residents of Mannahatta, as it was known to the Lenape, or New Amsterdam, the name given by Dutch colonizers. The ‘Land of the Blacks’ was the first settlement of its kind in New York, where Black residents owned land. On March 26, 1647, a man listed as ‘Bastien Negro,’ listed in other documents as Sebastiaen de Britto of St. Domingo, was granted six acres of the land that includes 143 Allen Street, extending from “the Bowery and Rivington St eastward towards Allen St, and downward towards Broome St.” Seven months after receiving this land, he married a woman named Isabel Kisana, from Angola; their marriage was recorded in the Dutch Reformed Church.

In 1644, William Kieft, the Director-General of New Amsterdam, oversaw the transfer of thirty land grants to enslaved people who had petitioned the Dutch West India Company for their freedom. Instead of full freedom, the Company only agreed on “half freedom,” a status with more participation in the Dutch colonial legal system, but with the conditions that they could be recalled into labor for the Company at any point, that they owed an annual tax to the company, and devastatingly, that their children would remain enslaved. The land grants were included in the agreement of “half freedom,” but the land given sat a mile north of the city boundary at today’s Wall Street, a perceived buffer between the Dutch colonial settlements and the Lenape Native American settlements.