Blog Archive

Picturing Child Labor: Lewis W. Hine

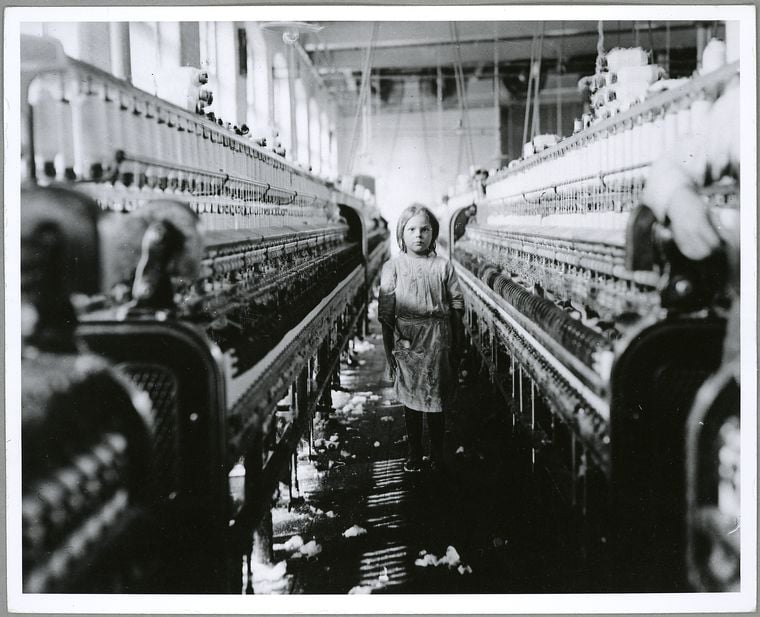

A child at a North Carolina cotton mill, captured by Lewis W. Hine. Photo courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Once you have seen a photograph by Lewis W. Hine it is hard to forget it. Though Hine himself is largely forgotten, his work, which documents child labor in early 20th century United States, continues to haunt lawmakers, photographers and civilians alike, as an arresting example of the power of the photograph.

The beginning of the 20th century saw a drastic increase in child labor, as the American economy began to shift from primarily agricultural work to manufacturing and industry. The Civil War put this transition on hold, but iron and textile production increased as reconstruction efforts led to the development of railroads for better transportation of goods. Farm work gave way to factory jobs, which provided more consistent income for families; the work was less dependent on the weather or the harvest. However, these laborers no longer had the opportunity to grow their own food and found wages shockingly low. Entire families had to work in these new factories in order to earn a living, and that included children. In 1890, 1.5 million children were at work, which rose to an alarming total of 2 million only a decade later.

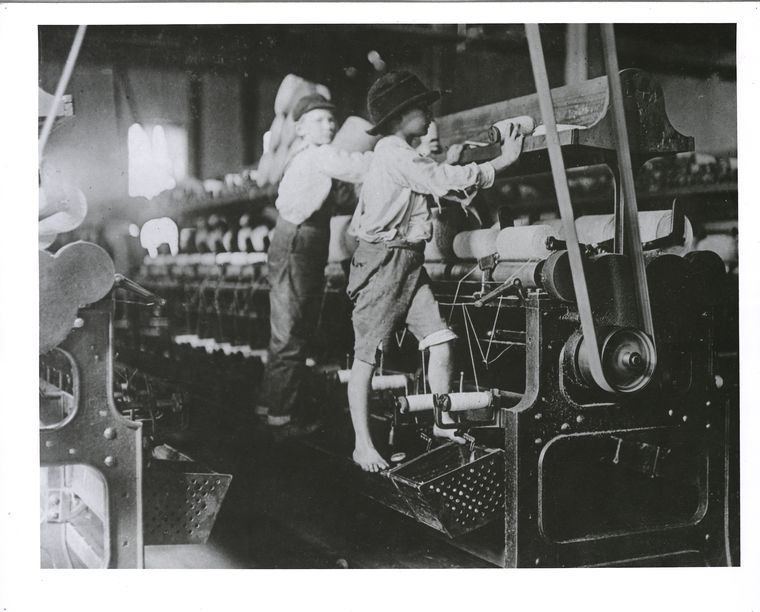

Not exactly a jungle gym: very young children working in a Georgia cotton mill. Though the children's smaller frames enabled them to move among the machines, they were also much more likely to become injured. Photo courtesy of the NYPL.

The conditions of the factories were lethal for workers of any age, but were especially deadly for children. Instead of fresh air and education, children inhaled chemical fumes and performed difficult, repetitive tasks on machines which were not built for workers of their size. These conditions resulted in stunted growth both physically and mentally. Most employers wanted to hide the role of child labor in their businesses, and many Americans looked the other way, reluctant to be faced with the reality of this pitiable practice. In 1904, to answer a growing demand for reform, a group of liberal activists founded the National Child Labor Committee. After receiving a charter from Congress in 1907, the Committee hired a variety of agents to investigate children in the work force.

Lewis W. Hine, a sociologist and a New York City school teacher, became one of the country’s strongest agents in fighting child labor. Hine joined the National Child Labor Committee as an investigative photographer, where he covertly photographed working environments and interviewed workers. Believing he could get the most truthful representation of child labor by hiding his activities both from the children and their employers, Hine would chat with the children and scribble their comments on a notecard hidden in his pocket.

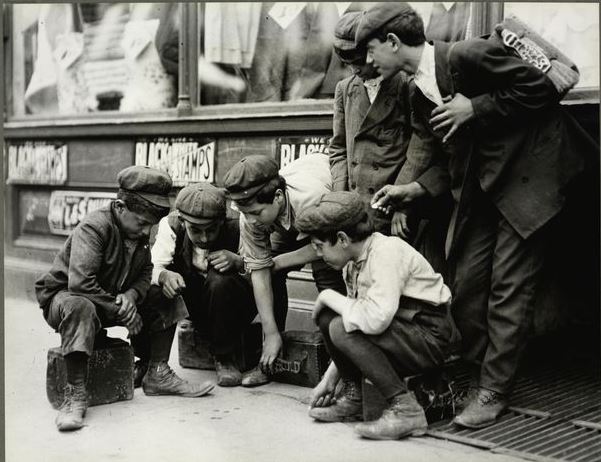

Young coal breakers in Pennsylvania. As steam engine travel increased, so did the need for coal. Photo courtesy of the NYPL.

Were Hine’s efforts successful? His images, which still speak to the pain of child labor a century later, drew attention to injustices that were painful to imagine and difficult to discuss. In 1916, the Keating-Owens Act passed, which limits the age at which children can begin working in what industry, how long they can work and other regulations. Hine himself died relatively unknown and impoverished, but a century later, it is clear the debt is ours.

Like Jacob Riis, whose images brought attention to poverty in New York City, Hine’s investigative photography was influential not only to government officials, but to the public who viewed his photos. Hine’s work also influenced a new generation of photographers: the seriousness and grace of his photos can be seen in the work of Margaret Bourke-White, who documented labor in the Soviet Union, and Walker Evans, who brought the realities of the depression to those who remained beyond its reach. According to Hine, a photograph can convey “a reproduction of impressions made upon the photographer which he desires to repeat to others.” He brought us his impressions and the knowledge that clear-sighted photography can help change the world.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator