The Burinescu Family lived at 97 Orchard Street during the waning years of the Progressive Era. In 1918, at the age of 39, the head of the family, Jacob, died at home from flu related complications.

Jacob Burinescu perished during the most intense period of the epidemic in New York as flu mortality was peaking. His death certificate shows him living at 97 Orchard Street. While this record is the earliest we see the family listed in the building, Jacob and his wife Sarah had lived in New York for almost 20 years by the time influenza claimed Jacob’s life.

Jacob was born in Romania in 1881 and immigrated to New York in 1900, at the age of 19.

Photo: Jacob Burinescu, c. 1910. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

His wife Sarah was born in Russia in 1885 and had moved to New York in 1897, around the age of 13.

Photo: Studio Portrait of Sarah Burinescu, c.1905. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

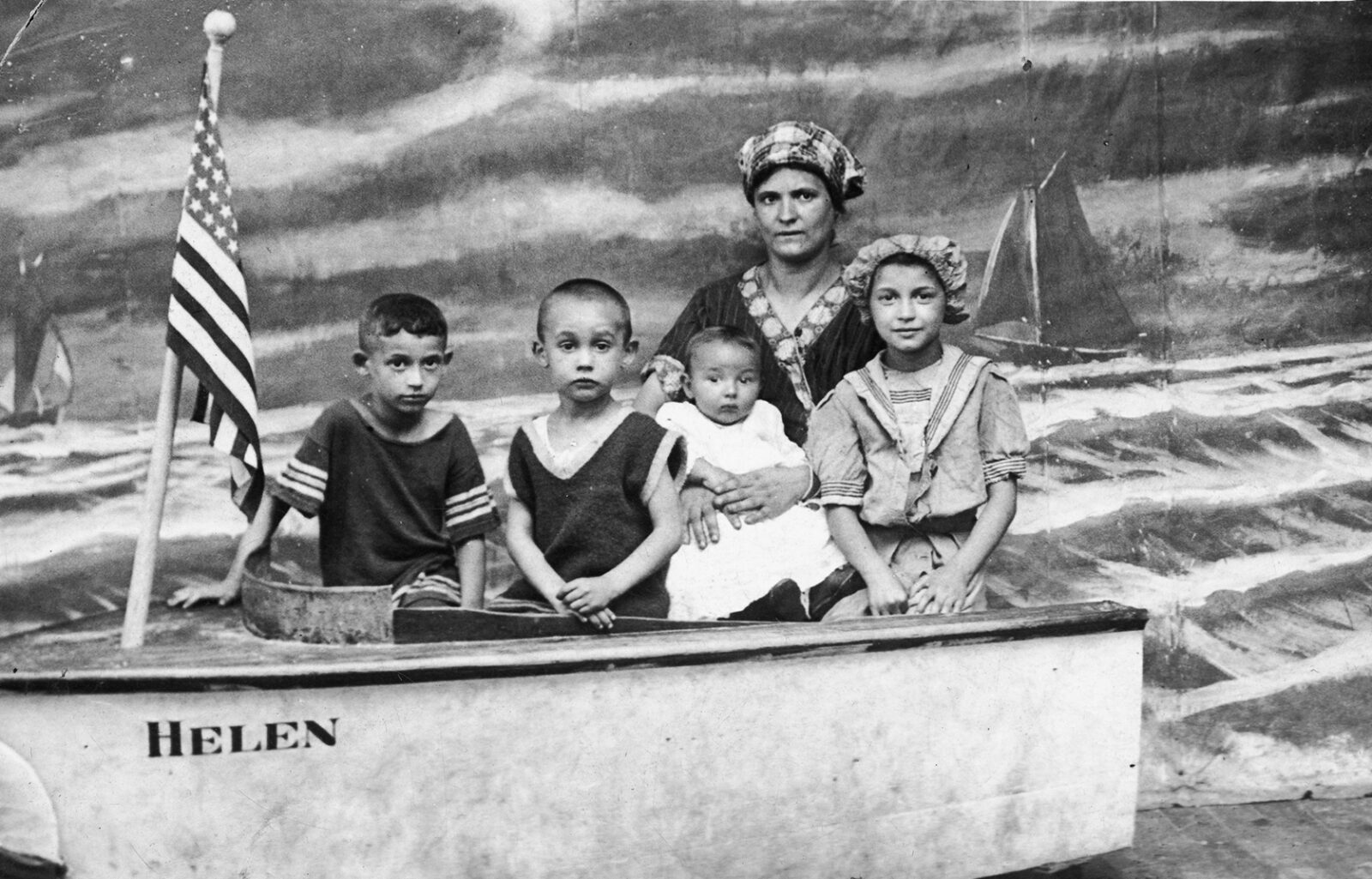

Their six children Celia, Boris, Abe, Phillip, Pearl, and Jaqueline, were all born in New York. Sarah became a naturalized US Citizen in 1910. The family lived on the second floor and remained at 97 Orchard Street until roughly 1927.

Photo: Sarah Burinescu and 4 of her children, c. 1915. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

Jacob and Sarah’s youngest child, Jacqueline Burinescu Richter (known within the family as “Jennie”) was interviewed with her daughters (Jacob and Sarah’s granddaughters) by Tenement Museum researchers in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s.

Jacqueline was born in January 1919, several months after her father became one of the flu pandemic victims –she never had the opportunity to meet or know him directly and everything she learned about her father came through memories shared by her mother and siblings. Jacqueline’s memories, combined with museum research, allow us to understand more about Jacob and Sarah’s lives.

Photo: Jaqueline Burinescu, c. 1935. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

An Actor and Businessman

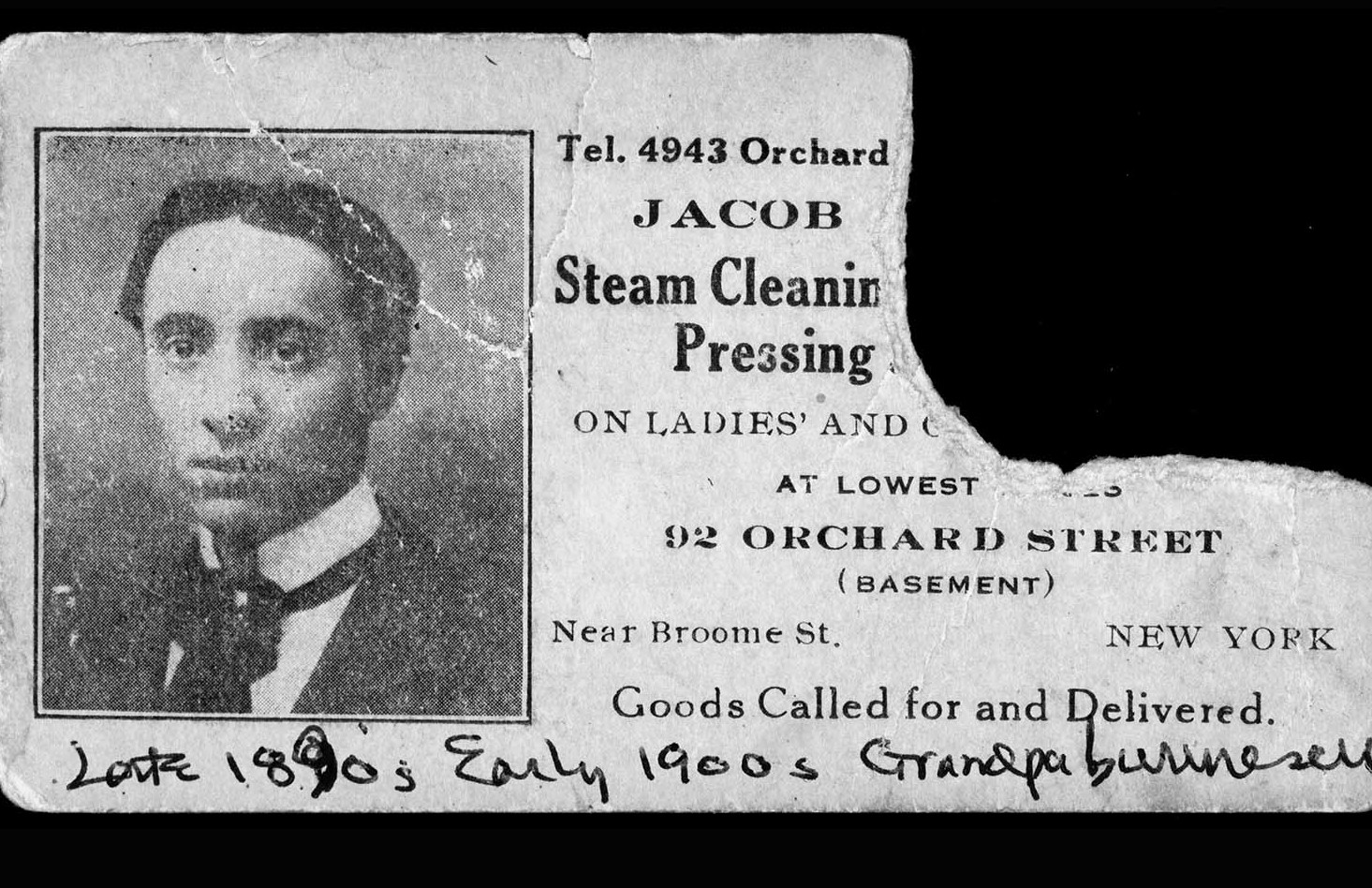

Jacob earned a living for himself and his family by running a steam cleaning and pressing business from the basement of 92 Orchard Street. Jacob was also an amateur actor, active in the Lower East Side’s Yiddish Theater community.

This steam cleaning and pressing business intersected with his involvement in Yiddish theater –many of his patrons trusted him to clean their costumes.

Photo: Calling card for Jacob Burinescu’s Steam Cleaning & Pressing Business. C. 1915 Collection of the Tenement Museum.

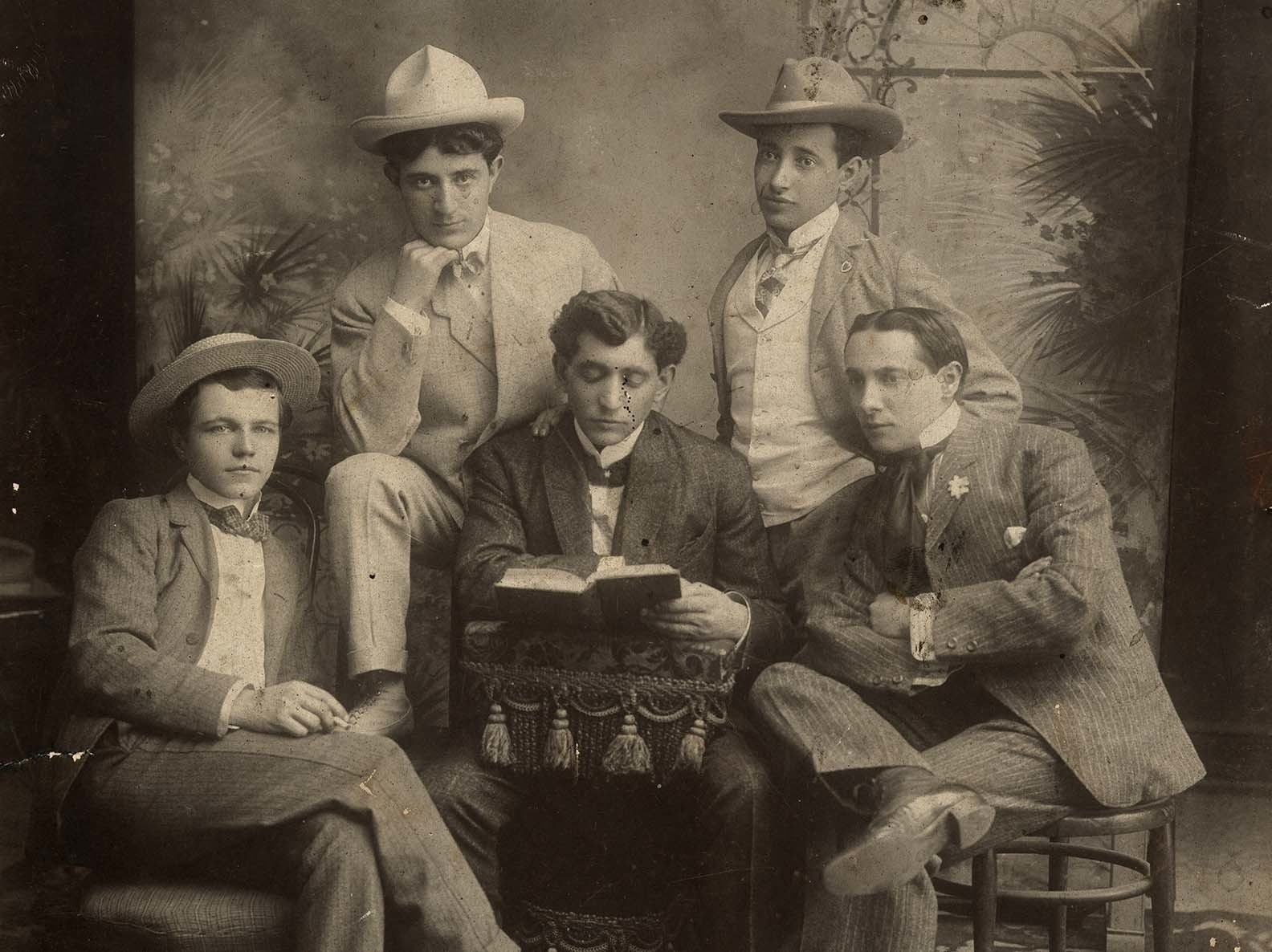

As an actor, Jacob was a member of an amateur Yiddish acting troupe, which also functioned as a landsmanshaft, or mutual aid society. When several of his friends and fellow members were stricken with influenza in October 1918, Jacob is said to have tended to them at their sick bed –making a point to visit them despite the danger of contracting the deadly virus himself. As Jacob’s decedents assert, he contracted the influenza in the first days of November, following bedside visits to his friends.

Photo: Studio portrait of Jacob Burinescu posing with members of his acting troupe, c. 1915. Jacob is seated at right. Collection of Tenement Museum.

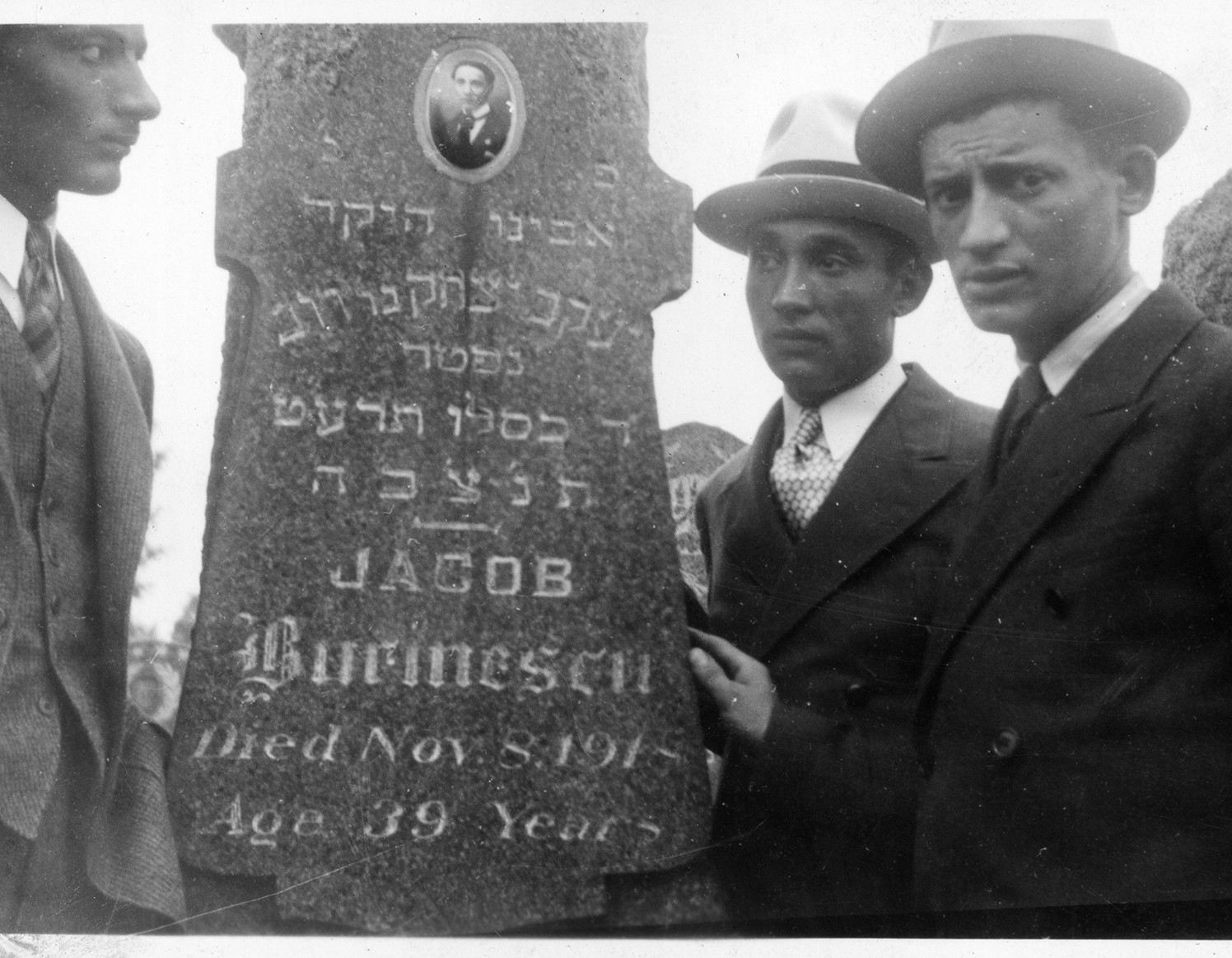

Jacob suffered with the flu for approximately a week. The doctor who signed his death certificate, Dr. Luegher, attended Jacob from November 3rd until his death on November 8th. His granddaughters recalled Jacob was the ‘president of a society,’ in reference to his Yiddish theater group. Members of these voluntary organizations contributed regular dues and had the capacity to withdraw benefits when sick or injured, and to help with the costs of burial upon death.

These landsmanshaft often owned burial plots for the society members and their families within the Jewish cemeteries on what were then the outskirts of the city. Additionally, these societies also often retained the services of a “lodge” doctor, who would visit and treat sick members who had become ill. Perhaps Jacob and his family took advantage of this benefit, and Dr. Luegher was this landsmanshaft’s lodge doctor.

Photo: Jacob Burinescu’s three sons, from right to left Abe, Jacob, and Bernie, standing by his tombstone in Baron Hirsch Cemetery on Staten Island, c. 1920s. Collection of Tenement Museum.

One of the Burinescu children also contracted the flu, at age three. As Jennie remembers: “She was only three years old at the time. They weren’t worried about her, they worried about him and he passed away from that.”

Coping with Loss

For Sarah Burinescu, the miracle of her daughter surviving the flu did not offset the loss of her husband and following Jacob’s death –in her third trimester of pregnancy with Jennie –she slipped into a situational depression. The depth of this depression was such that her family expressed concern for the health of her pregnancy.

Photo: Sarah Burinescu holding one of her children c. 1910. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

“My mother had me at the home and in fact she was kind of sick ‘cause you know she was still upset about my father’s death. So she was at home—and they had to be a little more careful with her, but thank God she was alright.”

– Jennie (Jaqueline) Burinescu

Following his death, Sarah Burinescu was left in the position of being the breadwinner. Sarah supported her family of six children by working in the garment industry as a sewing machine operator.

Photo: Studio Portrait of Sarah Burinescu, c.1925. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

She also became quite politically active, and was the first woman living at 97 Orchard Street to register to vote after woman’s suffrage was awarded in 1919.

Photo: Sarah Burinescu (second from left) posing with four women who belonged to a political club devoted to women’s suffrage, c. 1915. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

Jacob’s death had a powerful impact on the Burinescu family. As we look to the historic context, he was another victim of an epidemic that claimed the lives of over 30 million people worldwide. This unusually virulent strain of the influenza virus began in the Spring of 1918, and lasted in many countries for over a year.

At the end of 1918, Vincent Vaughan, Dean of University of Michigan School of Medicine, echoed what many medical professionals had observed in the midst of the great influenza pandemic:

“I dare say that the world has never before known a pestilence more widespread, more intensive and appalling in its progress, or more destructive to life, than this epidemic.”

– Vincent Vaughan, Dean of the University of Michigan School of Medicine

In the next section, we look at how the 1918 flu developed in New York City, and how officials responded to the most acute public health crisis the city had ever experienced.