The typical flu season begins in the colder months, with the first cases of each annual cycle appearing in early autumn. However, the 1918 viral strain uncharacteristically began in the spring, coinciding with warmer temperatures, before tapering off in the summer and then returning in a devastating second wave in the fall. Contemporary health officials now believe that between March and October 1918, the virus evolved to become ten times more virulent. The virus was first confirmed in New York City in August of 1918.

The flu outbreak occurred while World War I raged in Europe, and the war dynamics gave the flu its commonly known name, the Spanish Flu. The nations directly involved in the war maintained a pact not to report on the flu outbreak. Spain, as a neutral nation, reported accurate news and information about the number of people suffering, leading Spain to be identified closely with the virus.

Slow Responses and Conspiracy Theories

Across the ocean in New York, the first confirmed case of influenza was reported on August 14, 1918, and the first death was recorded a month later on September 15th. New York public health officials had gained a global reputation for their rapid and thorough response to health crises following their previous campaigns against tuberculosis and polio, and yet the city took no discernible action when the death was reported.

Within three days, the hospitals were filled with patients with the same symptoms, but the city denied that these were the notorious Spanish influenza cases that had begun to spread panic. While the city didn’t openly acknowledge these first cases, on September 17th the Board of Health expanded the Sanitary Code to make influenza and pneumonia reportable for the first time in New York history.

Military officials and the American press had done little to raise the alarm during the months of intensification through the summer, focusing their attentions instead on how hard the flu was hitting the enemy. The seriousness of symptoms reported amongst German soldiers was attributed to exhaustion and hangovers, while headlines frequently boasted of “No Influenza in Our Army.”

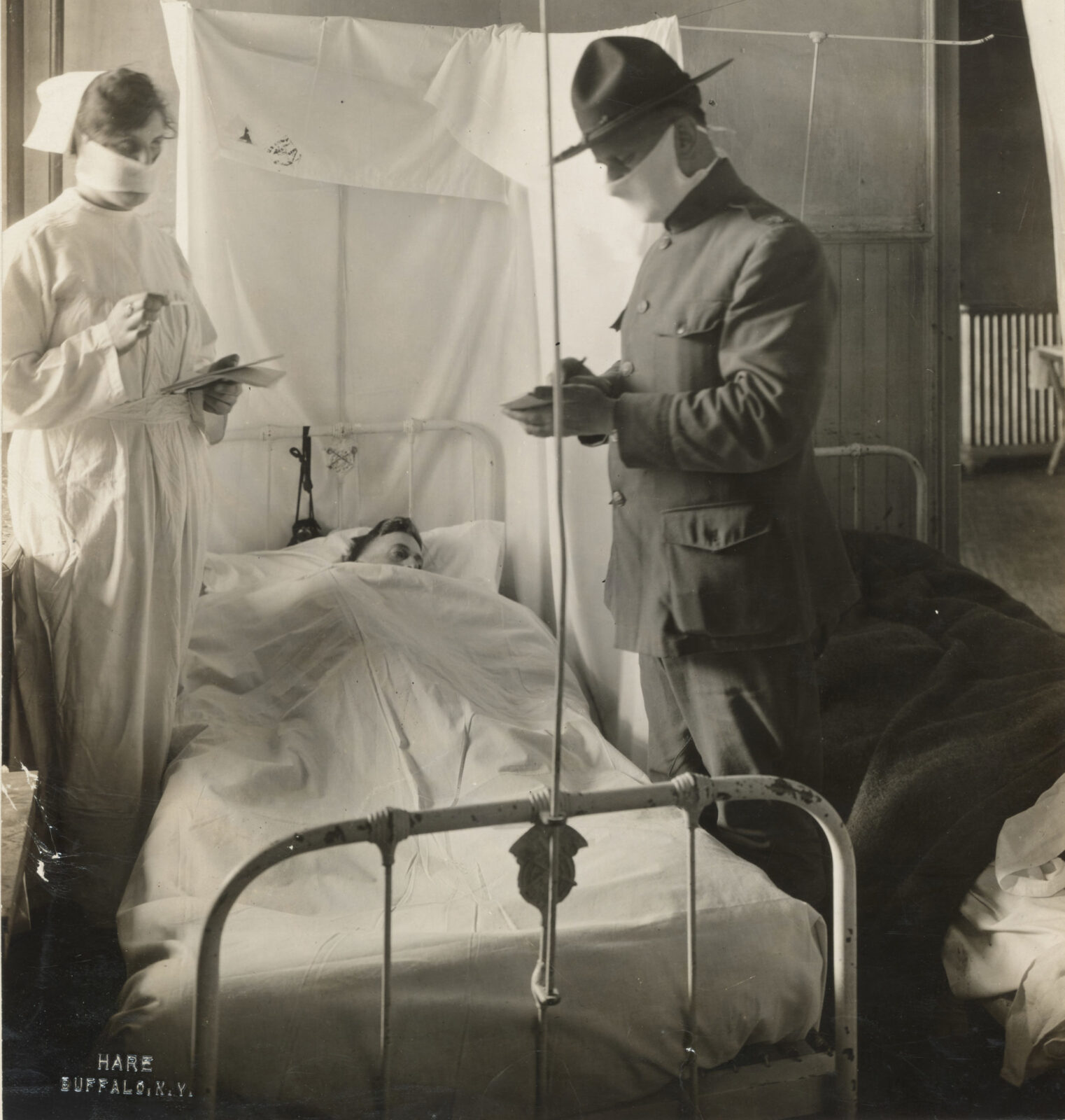

Photo: “Spanish Influenza in an Army Hospital.” Fort Porter, NY. November 19, 1918. Collection of National Archives and Records Administration.

A combination of fear and wartime patriotic fervor went so far as to blame German and German-American spies for spreading the sickness —conspiracy theories ranged from germs being sprayed into the air to being injected into German-made Bayer aspirin.

Identifying the Symptoms

Early autopsies were conducted by military doctors, and revealed lungs so ravaged that some doctors feared they were dealing with a new disease altogether, something worse than the bubonic plague. These reports noted some lungs weighing six times their normal weight and having the consistency of “melted redcurrant jelly.” People’s lungs were filled with a bloody, frothy liquid —leaving no space whatsoever for air, and some autopsies showed torn abdominal muscles and damaged rib cartilage from coughing so hard.

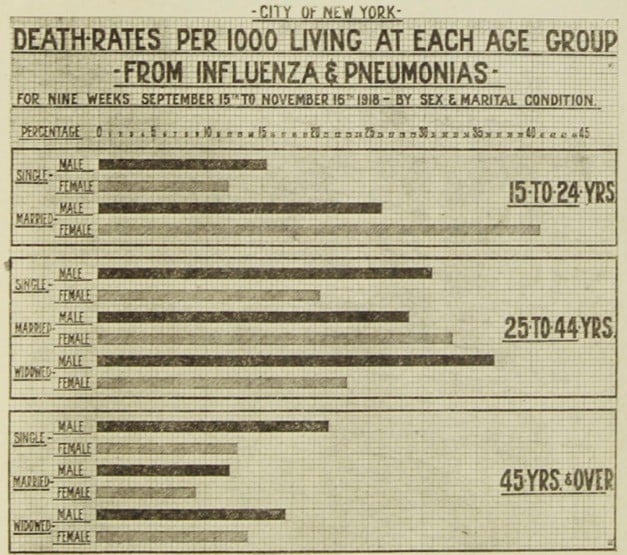

Initial anxieties that the world was facing an unknown disease were fueled by the fact that the virus was notably deadly among people ages 15- 45, and in particular 25-34, rather than just among the very young and very old. Although it killed more men than women, likely skewed by data on soldiers, pregnant women were nonetheless most likely to die if infected.

Photo: “Death Rates per 1000 Living at Each Age Group – From Influenza and Pneumonia“ November 1918. Collection of New York Municipal Archives

Even those who did not endure these severe complications experienced unbearably intense flu symptoms, being bedridden for weeks with high fever, aching bones, extreme lethargy, headaches, pain and inflammation in the eyes, inflamed nose and throat, and an extreme cough. Patients described great difficulty breathing and overwhelming exhaustion, symptoms that left some with permanent heart, liver, and kidney damage.

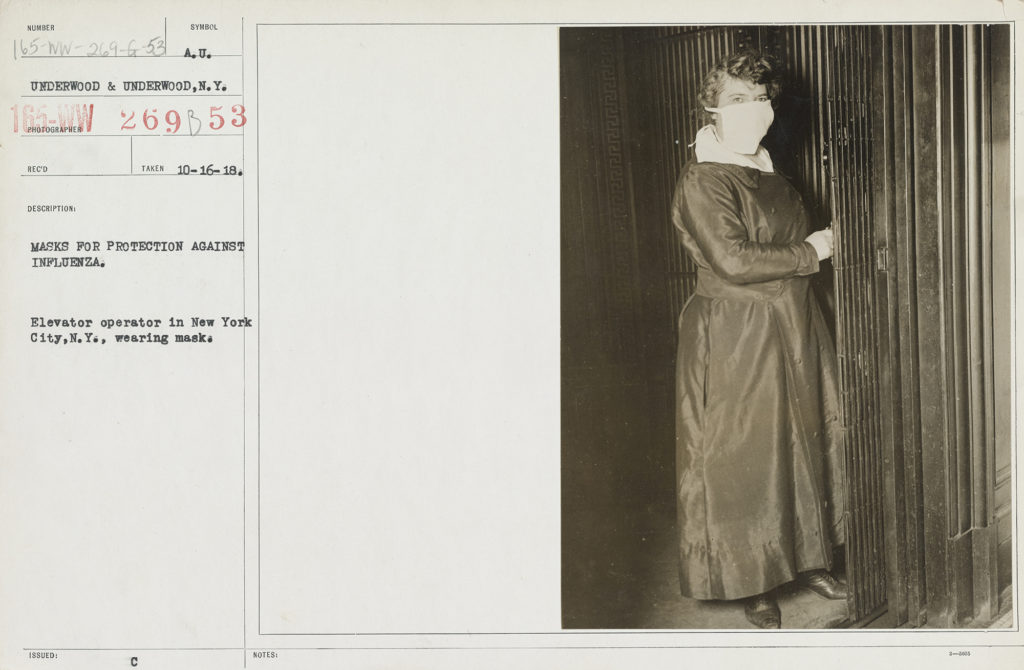

Photo: New York Elevator Operator Wearing Mask during Influenza Pandemic, October 16, 1918. Collection of National Archives and Records Administration.

While the strain that circulated the globe in 1918 was especially virulent, influenza had long been catastrophic for marginalized communities in general, and both people who were impoverished and people who were homeless in particular. The people who make up these communities are historically disproportionally affected by illness- even the most common ones. What continued to be so alarming about the 1918 pandemic is that it was such an ordinary and expected illness —nothing more than the flu, yet a version of the flu that was entirely extraordinary and unexpected. The Science journal notes with alarm:

“The epidemics now occurring,” they observed, “appear with electric suddenness, and, acting like powerful, uncontrolled currents, produce violent and eccentric effects. The disease never spreads slowly and insidiously. Where it occurs, its presence is startling.”

-The Science Journal

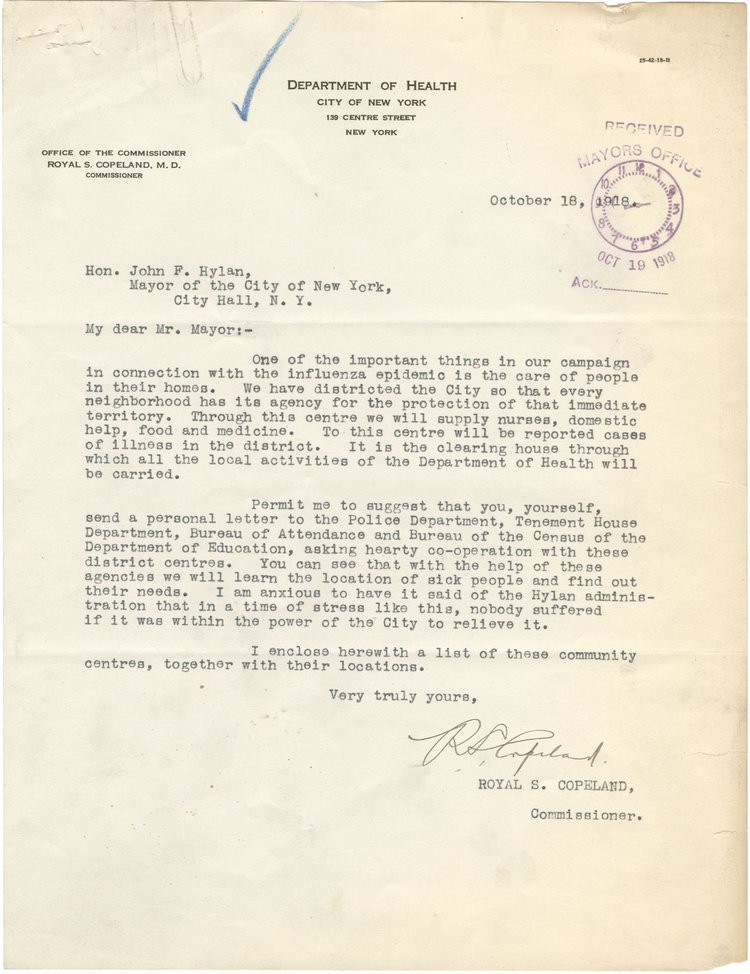

New York’s public infrastructure was already strained by wartime and the city, like most, suffered labor shortages at every level —from gravediggers to medical professionals. With the Democratic Tammany Hall return to power in January of 1918, the city’s public health services were further burdened. Tammany Hall, historically accused of cronyism for their political appointments, placed homeopathic physician Royal S. Copeland in the position of Health Commissioner. Copeland’s approach to public health clashed with proponents of modern scientific medicine, particularly those toiling in the Bureau of Laboratories to identify the particular organism behind the pandemic.

Photo: Letter from New York Department of Health Commissioner Royald S. Copeland to Mayor John Hylan regarding response to Influenza epidemic. October 18, 1918. Collection of New York Municipal Archives

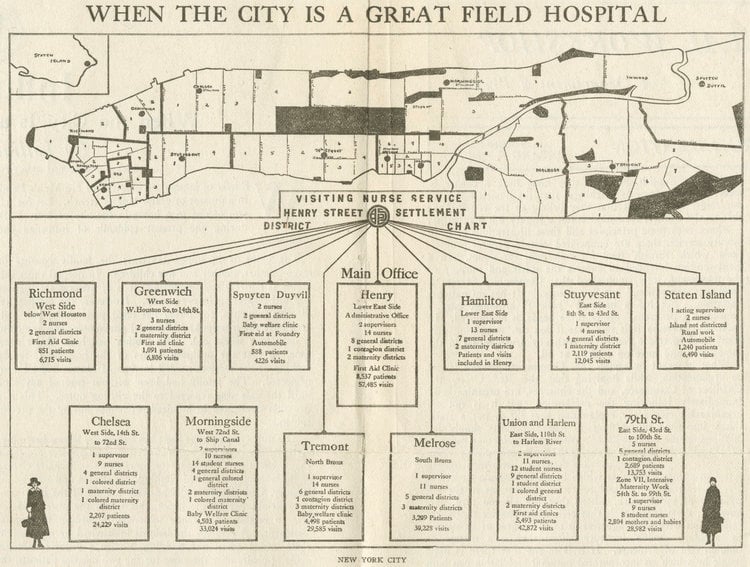

Health officials formally recognized that an epidemic was unfolding on October 4. This official announcement was followed by two weeks of mounting death- these fatalities only the first lost to what would be three cycles the virus would make through the city. On October 7, health officials enacted plans to divide the city into 150 emergency health districts, each assigned temporary health centers functioning as clinics as well as headquarters for nurses who provided home health care.

Photo: “When the City is a Great Field Hospital” Manhattan map indicating locations of influenza clinics throughout the city, October 1918. Collection of New York Municipal Archives.

Home nursing proved essential to the public health response to the epidemic, work implemented and overseen by Lillian Wald, founder of the Henry Street Settlement on the Lower East Side.

Photo: Lillian Wald in nursing uniform, 1900. Source unknown.

With emergency appropriations and reassignments from the Tenement House Department, the Department of Health was able to expand its public health inspectors. Finally, the Board of Health completely reorganized the administrative structure of the Department of Health, giving much more authority to each borough’s sanitary superintendents and their respective staffs.

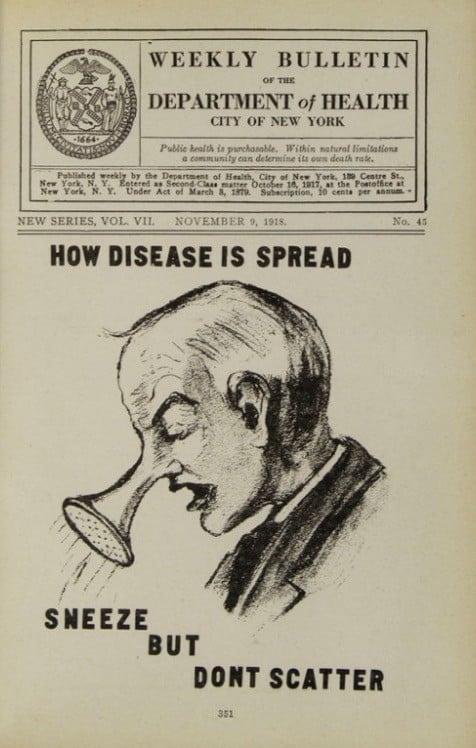

Hiring additional health workers was the second largest use of emergency appropriations made by the city to address the epidemic. The first and largest went toward printing health education materials.

“Sneeze but Don’t Scatter”

By September 24, health officials had placed at least 10,000 posters in subway and railway stations, elevated train platforms, street cars, store windows, police precincts, hotels, and other public spaces.

Photo: Public Broadsides carried the same message as this Weekly Bulletin of New York Department of Health “How Disease is Spread/Sneeze but Don’t Scatter” published on November 9, 1918. Collection of New York Municipal Archives.

A public campaign featuring broadsides printed in in English, Yiddish and Italian- the latter two languages aiming to reach the immigrants living in Lower Manhattan —worked to make New Yorkers aware of the dangers and risk factors of influenza. These posters conveyed three different messages: one series instructing people to cover their coughs and sneezes, one series encouraging people not to spit, and one urging New Yorkers to “Help to Prevent the Return of the ‘Flu’ and Pneumonia!”

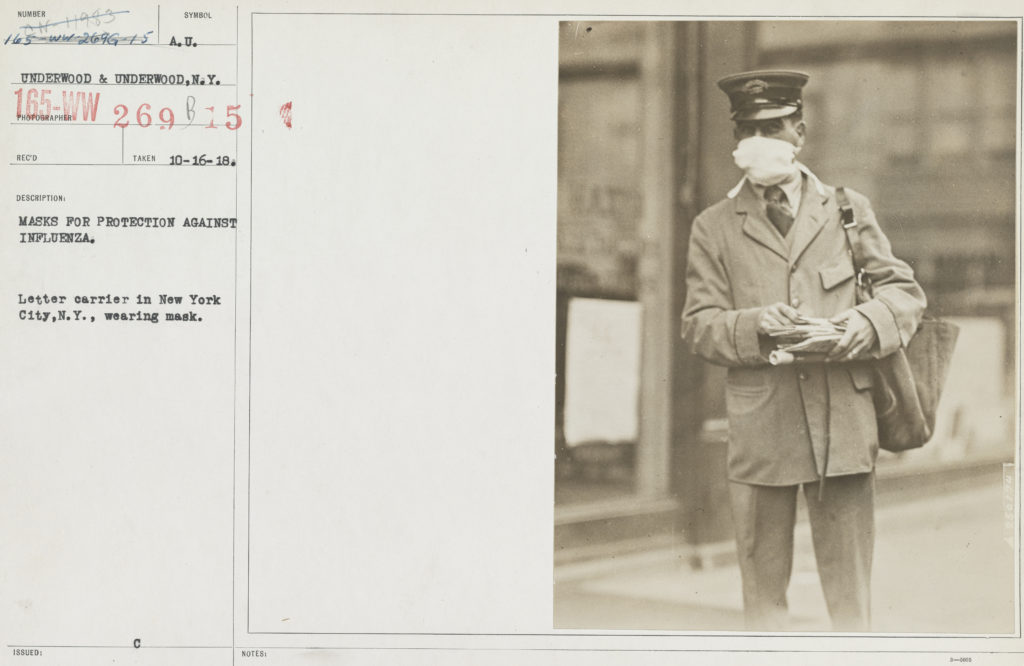

Along their daily routine, Jacob and other members of the Burinescu family may have seen these posters. Undoubtedly, they became well-acquainted with the sight of New Yorkers and city government employees covering their faces with clean handkerchiefs and gauze masks.

Photo: “Letter Carrier in New York Wearing Mask.” October 16, 1918. Collection of National Archives & Records Administration.

The Federal Government Reacts

Mounting patient counts and death tolls in the fall of 1918 forced local and federal governments to address the realities of the pandemic and to act quickly. Mayors and governors had been pleading for weeks against the Surgeon General’s inaction before Congress hastily appropriated one million dollars toward the Public Health Service and moved 5,000 doctors into a month of emergency duty. Local papers began to publish official warnings from the federal government. The broadside campaign combined education and mortal fears, with slogans like “Wear a mask and save your life!” Gauze masks became mandatory and spitting and coughing in public were made punishable offenses. Public gathering was strongly discouraged if not outright banned. Theaters closed nationwide, as well as lodges, restaurants, saloons, skating rinks, dance halls, schools, and churches (New York was an exception to many of these closures, as detailed below). Even the National Association of the Motion Picture Industry shut down for a month. Couples were even encouraged to wear cotton handkerchiefs while kissing. A resident of Washington DC summarized the period:

“We were afraid to kiss each other, to eat with each other, to have contact of any kind. We had no family life, no school life, no church life, no community life. Fear tore people apart.”

-Washington DC resident

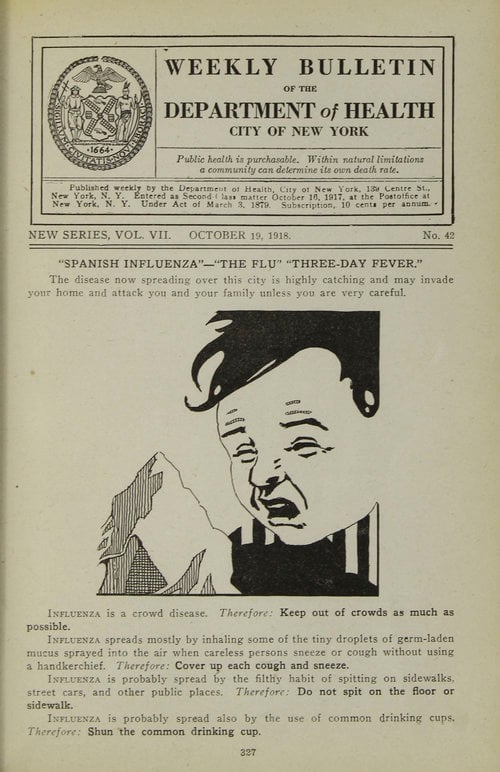

Reporting in Immigrant and Working-Class Neighborhoods

While the flu struck throughout the city regardless of ethnic origin or class, the response was different, especially along class lines. Confirmed cases of influenza in private houses or apartment buildings were supposed to be placed under quarantine. Neighborhood health workers employed this policy of medical isolation for all cases found in boarding houses and tenements, and people stricken with the flu were removed to city hospitals. However, enforcing isolation proved as difficult as identifying new cases, and many patients in the densely crowded lower Manhattan neighborhoods went unreported. Doctors and health workers on the Lower East Side, were “mobbed by women demanding their services.”

Photo: Public Broadsides carried the same message as this Weekly Bulletin of New York Department of Health “Spanish Influenza/The Flu – Three Day Fever” published on October 19, 1918. Collection of New York Municipal Archives.

To aid the efforts downtown, the city defaulted to a strategy of surveillance. Inspectors “on loan” from the Tenement House Authority canvassed door-to-door, hoping to track down previously undocumented cases. Health officials also revived a practice utilized at the turn of the century to weed out tuberculosis cases —enlisting landlords and janitors to report on their tenants.

Health Commissioner Copeland also appealed to Tammany Hall to enlist its party machinery to identify additional influenza cases, a move described by the New York Times as “highly unusual.” As the article elaborates:

“The entire organization, with its election district captains, was turned over to the Department of Health to aid Commissioner Copeland in the Spanish influenza epidemic.”

In another controversial decision, Health Commissioner Copeland chose to keep public schools open —going against the grain of contemporary conventional wisdom. In an October 5 New York Times article, Copeland explained his decision:

“New York is a great cosmopolitan city and in some homes, there is careless regard for modern sanitation…In schools the children are under the constant guardianship of the medical inspectors. This work is part of our system of disease control. If the schools were closed at least 1,000,000 would be sent to their homes and become 1,000,000 possibilities for the disease. Furthermore, there would be nobody to take special notice of their condition.”

– Royal S. Copeland

Health Commissioner of New York City quoted in the NYTimes

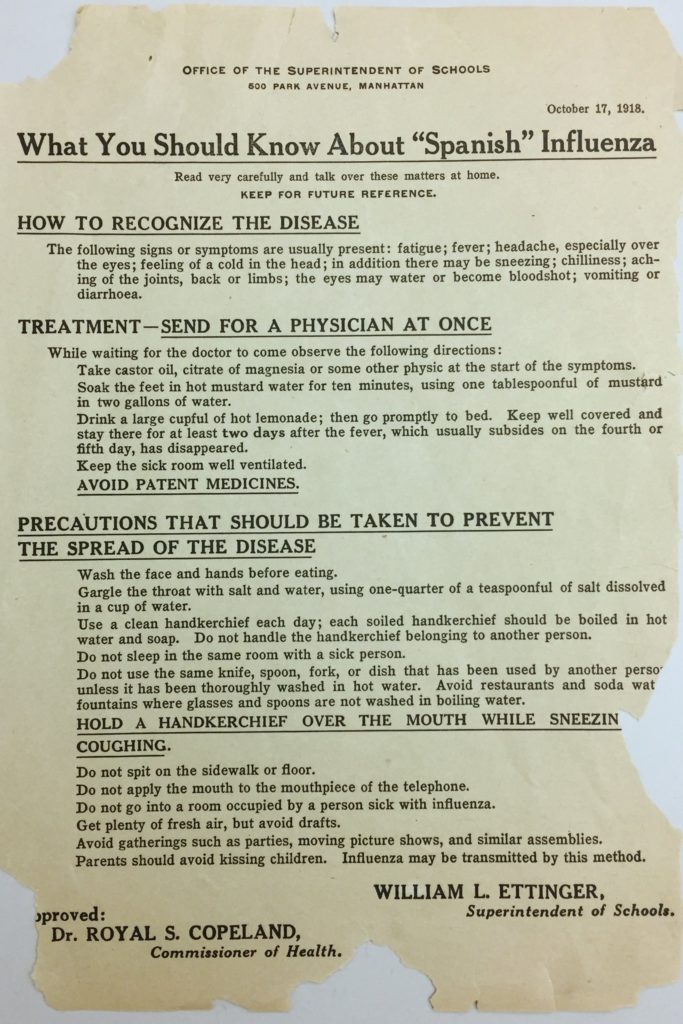

Photo: Notice from Superintendent of New York Schools to parents “What You Should Know About ‘Spanish’ Influenza,” October 17, 1918. Collection of New York Municipal Archives.

Copeland’s staff made every effort to back this reasoning —namely that the city could do a better job keeping children healthy than their parents and caregivers. By the end of September, the city had distributed nearly one million educational circulars, enough for every student enrolled in public or parochial schools to take one home. Teachers were required to report symptomatic children to school medical authorities, and absences were followed up with home visits from school nurses or local doctors.

Copeland’s team followed a similar logic as theaters and movie houses, arguing that despite the risk, they were prime sites to educate captive audiences about influenza. On October 11, the city did ban children younger than 12 from attending movies and shows (which would have included all of the Burinescu children, save the eldest, Celia) and also forbid dry sweeping, overcrowding, and smoking. Theaters were required to open all their windows and doors during off-hours and were subject to increased inspections. Confident as Copeland seemed in this approach of education and surveillance, there were many who took issue with his strategy, including the Red Cross of Long Island and former Health Commissioner Dr. S.S. Goldwater, who cited the “almost criminal laxity” of in-school inspections and care. Given the many children from immigrant households in New York City’s schools in 1918, Copeland’s approach to care created an additional risk factor for immigrants.

Black Crepes on Practically Every Door

With 9,000 people perishing in New York in October 1918 alone, one New York resident recalled people were “dying like leaves off of the trees.” Another explained, “The deaths were so sudden it was unbelievable…You would be talking to someone one day, and hear about his death the next day.” Doctors, nurses, and coffin makers labored day and night, and in cities nationwide wagons paced the streets each day to collect the dead. Week after week in hospitals, doctors and nurses would return to their critical patients each morning to discover that they all had died. The highest rates of death were among the poor, mostly among Italian and Russian Jewish immigrants. Xenophobic responses to the unfolding catastrophe extended beyond blaming German immigrants, placing blame for the outbreaks on foreigners, specifically those who seemed to suffer the most losses from the virus.

One Manhattan resident remembered how the city looked during the crisis:

“Everywhere around there were black crepes on practically every door, indicating the death of someone in the home. The hospitals were filled to capacity, and any large, vacant building would be used to house the ill and the dying. Not too many people wanted to be part of picking up the dead.”

-Manhattan Resident

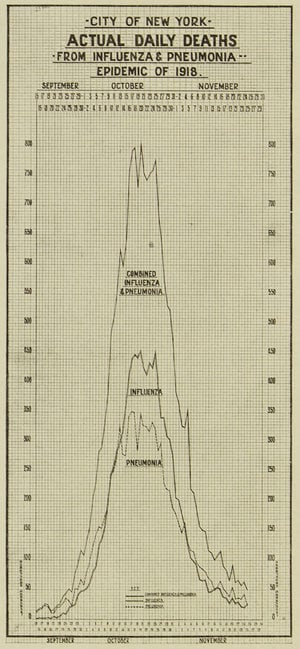

In total, over 33,000 people died of the flu in New York over two years.

Contemporary scholars argue this number is unrealistically low given that statisticians arbitrarily stopped counting victims and almost certainly missed many people in their efforts before that. Although here we look at the deadly weeks of late 1918, the eight weeks of the epidemic’s final cycle in 1920 contributed thousands more to that rough total.

Photo: City of New York graph illustrating” Daily Death Totals From Influenza and Pneumonia/Epidemic of 1918.” Collection of New York Municipal Archives.

Following the slow and inconsistent accounting of the people lost, the City of New York further concluded that at least 21,000 children had been orphaned by the epidemic. These figures, mirrored in cities and towns around the world, and considered alongside the symptoms and suffering, left people with trauma and long-term physical, psychological, and neurological damage in the wake of the influenza pandemic.

The fact that the flu remained an everyday illness that would return in milder forms each year, paired with the spirited arrival of the Roaring Twenties, contributed to the collective amnesia that followed this global pandemic.

The collective sense of helplessness and panic, rapid onset of symptoms, and the sudden loss of life of the Influenza of 1918 occurred in the shadow of the First World War. More people died in the influenza outbreak of 1918 than in World War I. Memorials to those lost in the war stand tall throughout the United States, yet few towns and cities have erected memorials to those who died in the pandemic.

We turn next to a story of a couple impacted by AIDS, and a story of the grassroots fight for recognition, remembering, and memorials to those lost.