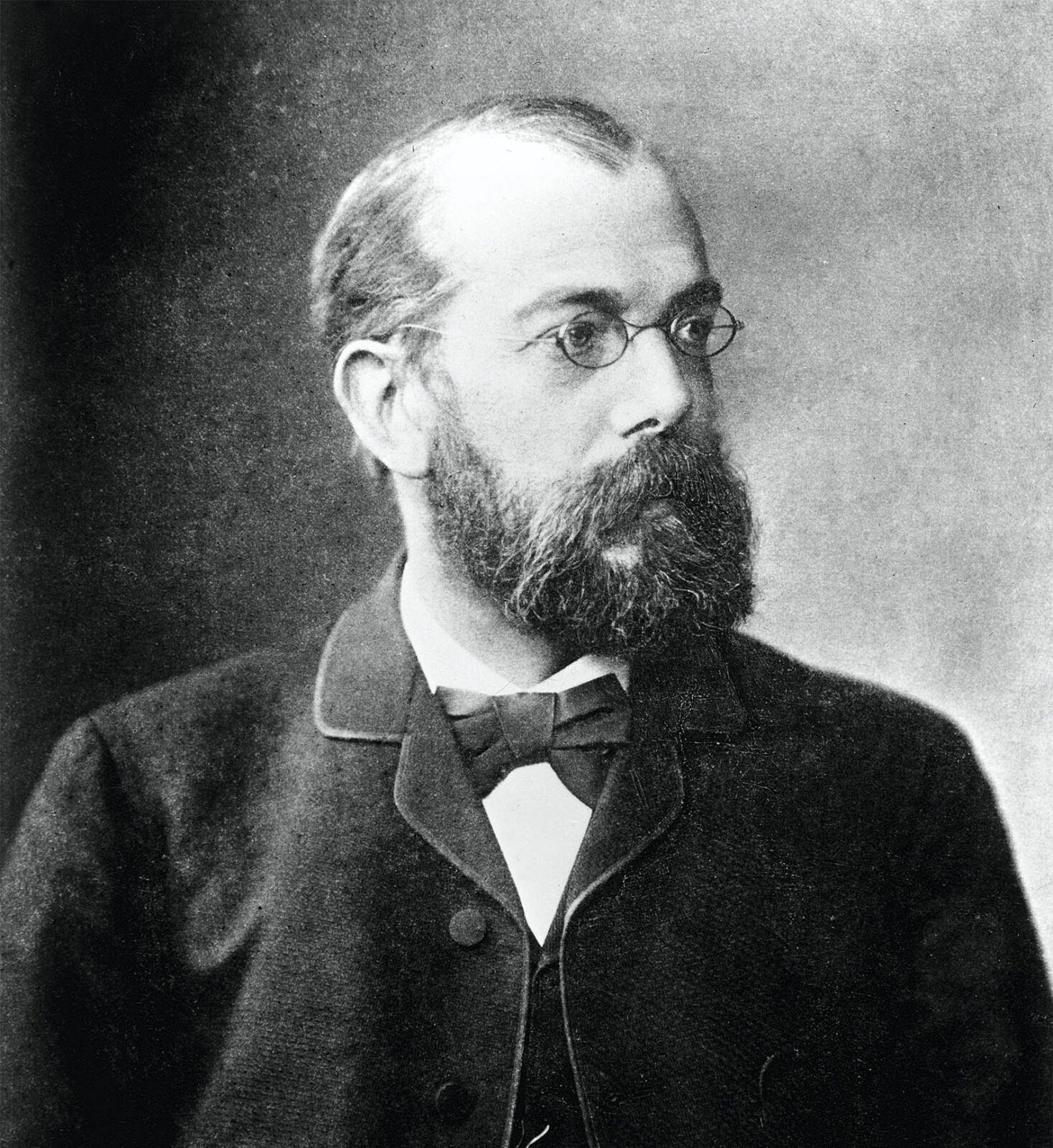

In 1882, Herman Koch had a breakthrough in his microbiology research.

He published his conclusion: that specific bacteria (not moral failing, ethnicity, or poverty) were the cause of contagious diseases. His research provided indisputable evidence that consumption (tuberculosis) was most readily transmitted between people through respiratory secretions, such as coughing.

While it took several decades more for this pioneering research to bear fruit, the 1880’s represent a paradigm shift in medical science. The seven years between Caroline and John’s deaths saw great strides in the understanding of tuberculosis, and the city of New York began to revolutionize its approach to preventing and treating the disease.

Photo: Robert Koch, late 19th century. Source Unknown.

Unlike contagious diseases such as yellow fever and cholera, which struck cities in concentrated outbreaks, and sweeping epidemics, tuberculosis was an endemic problem -which means it is regularly found among a particular group or area. It was popularly known as ‘the White Plague,’ due to the drained complexion of its sufferers, and was the deadliest disease affecting the United States and Europe through the 1800s and early 1900s.

John and Caroline were by no means alone in their illness: standard data indicates tuberculosis was responsible for nearly half of the deaths of people ages 15-35 in the United States during the 19th century.

Photo: “Girls’ classroom instruction about tuberculosis.” C. 1900. Jacob Riis. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

To live with the constant threat and presence of this illness was to know the constant cough and the pervasive rale, or the crackling sound made by lungs straining to breathe. Consider Charles Dickens’ famous description in Nicholas Nickleby of death from tuberculosis in 1839:

“There is a dread disease which so prepares its victim, as it were, for death; which so refines it of its grosser aspect, and throws around familiar looks unearthly indications of the coming change; a dread disease, in which the struggle between soul and body is so gradual, quiet, and solemn, and the result so sure, that day by day, and grain by grain, the mortal part wastes and withers away, so that the spirit grows light and sanguine with its lightening load, and, feeling immortality at hand, deems it but a new term of mortal life; a disease in which death and life are so strangely blended, that death takes the glow and hue of lie, and life the gaunt and grisly form of death; a disease which medicine never cured, wealth never warded off, or poverty could boast exemption from; which sometimes moves in giant strides, and sometimes at a tardy sluggish pace, but, slow or quick, is ever sure and certain.”

– Charles Dickens

Early tuberculosis symptoms were vague and elusive, described as “severe bodily or mental fatigue” or “a short and insidious cough, with a feeling of lassitude, and a decline in general health.” One could live for years, even decades with the disease, having “survived” but never fully recovered, marked by a rattling cough, fatigue, night sweats, and a general feeling of “wasting away.” As the disease progressed, a victim would begin to feel a burning and aching in their chest and cough up thick, white phlegm and blood. They would lose their appetite, and muscle mass. Death eventually came when enough liquid had built up in the lungs that they cannot get enough oxygen and their respiratory system fails.

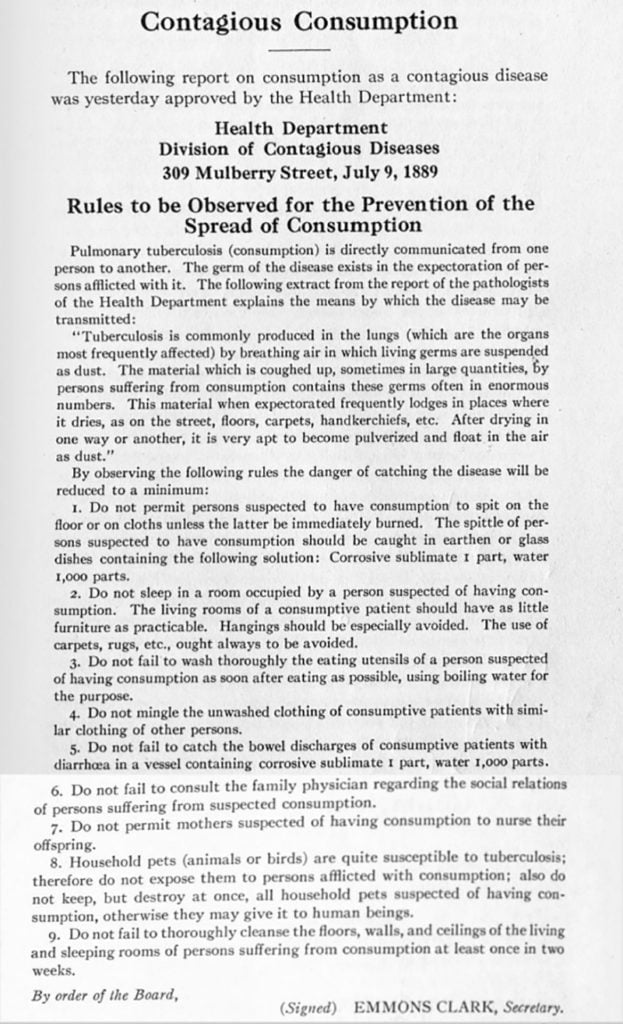

The first formal public health campaign in the country to fight tuberculosis began in New York in 1893, the year after John Schneider’s death. Hermann Biggs, the general medical officer of the New York Department of Health had been able to make major advances in bacteriology without intervention from the reigning political power, because he had once treated a local Tammany Hall boss.

Under his direction, the New York Department of Health was the first to translate this new knowledge of bacteriology into practice through new policies including mandatory reporting of cases, anti-expectoration ordinances, as well as dispensaries, hospitals, and sanitoriums specifically for tuberculosis treatment.

Photo: Herman Biggs, General Medical Officer, New York Department of Health. C. 1900. Collection of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Photo: “Contagious Consumption” New York Health Department Leaflet. 1889. Collection of New York Academy of Medicine.

By the 1890s Progressive Era reformers like Jacob Riis, Lawrence Veiller, and Robert DeForest had mobilized to put this epistemological revolution of disease causation in into practice, bringing photo documentation, medical statistics and demography, and dispassionate eye-witness accounts to advocate for changes to the built environment that would help prevent the spread of contagious disease and improve overall public health. Like the earlier efforts to minimize the impact of cholera conducted by the Citizen’s Association, inspection and evaluation of immigrant populations was a primary part of Progressive Era reform.

Advancements in understanding the bacterial origin of diseases and how they spread did not quell the fear among reformers. Their fearful and paternalistic attitudes manifested in the combination of heightened surveillance and re-education of New Yorkers –with a particular focus on immigrant communities.

In the next section, we’ll look at how the 1918 Influenza profoundly impacted an immigrant family living in 97 Orchard Street.