Enter Jane Jacobs, a neighborhood activist known for her seminal work The Death and Life of Great American Cities. After frustrating Moses’ plans in the West Village, she was asked to help halt the construction of the new highway. Quickly forming the Joint Committee to Stop the Lower Manhattan Expressway, Jacobs hosted rallies, wrote jingles and op eds, and even got arrested for protesting a meeting in 1968.

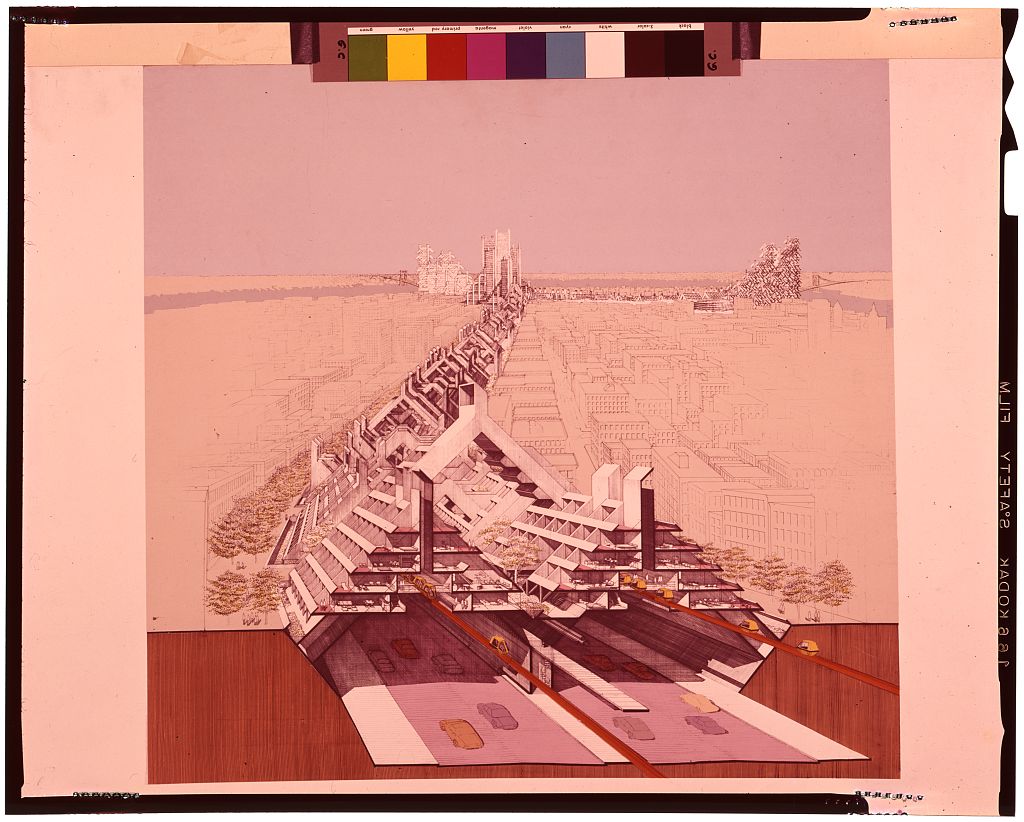

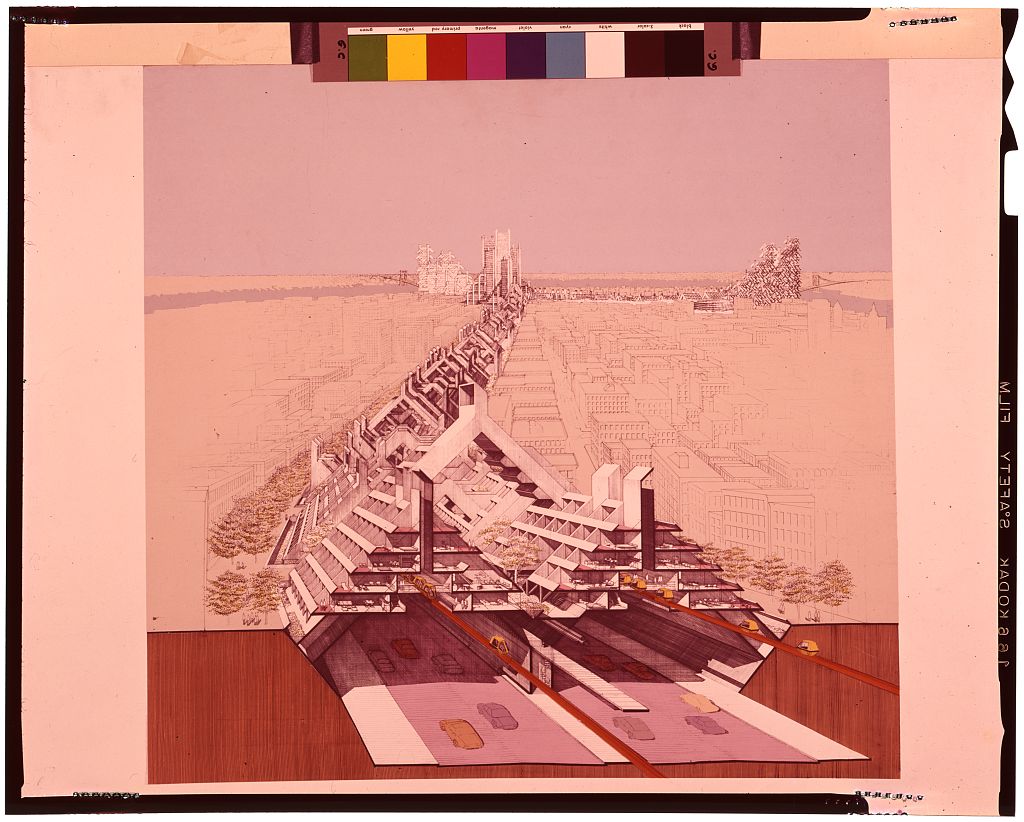

By the time of Jacob’s arrest, LOMEX’s position was tenuous, a 1962 budget request for the highway was rejected. Before the final blow though, one last idea for LOMEX was floated. Architect Paul Rudolph was brought on to reimagine the project by burying it underground. The subterranean highway would only be a part of Rudolph’s striking design. Buildings, some sixty stories tall, made out of prefabricated concrete pieces were to be assembled along the route of the highway.

Grand and bold in its design, and akin to something out of a World’s Fair exhibit or the futuristic world of Blade Runner, Rudolph’s designs too would not come to fruition. Neighborhood activism like that practiced by Jacobs and others was only a part of LOMEX’s demise. Apathy on the part of subsequent mayoral administrations, New York’s increasing fiscal decline and concern over the loss of historic architecture were wrapped up in a larger rejection of urban renewal. s we consider how infrastructure and urban design will adapt to our current challenges, the story of LOMEX is one that illustrates the roles of government, community, and industry in shaping our cities.

Grand and bold in its design, and akin to something out of a World’s Fair exhibit or the futuristic world of Blade Runner, Rudolph’s designs too would not come to fruition. Neighborhood activism like that practiced by Jacobs and others was only a part of LOMEX’s demise. Apathy on the part of subsequent mayoral administrations, New York’s increasing fiscal decline and concern over the loss of historic architecture were wrapped up in a larger rejection of urban renewal. s we consider how infrastructure and urban design will adapt to our current challenges, the story of LOMEX is one that illustrates the roles of government, community, and industry in shaping our cities.

Written by Jakub Gaweda, Tenement Museum Education Specialist