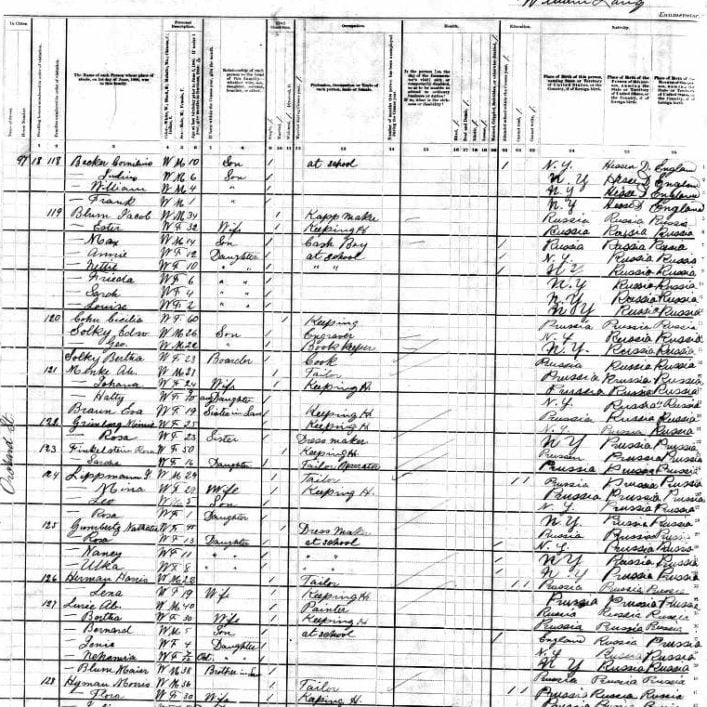

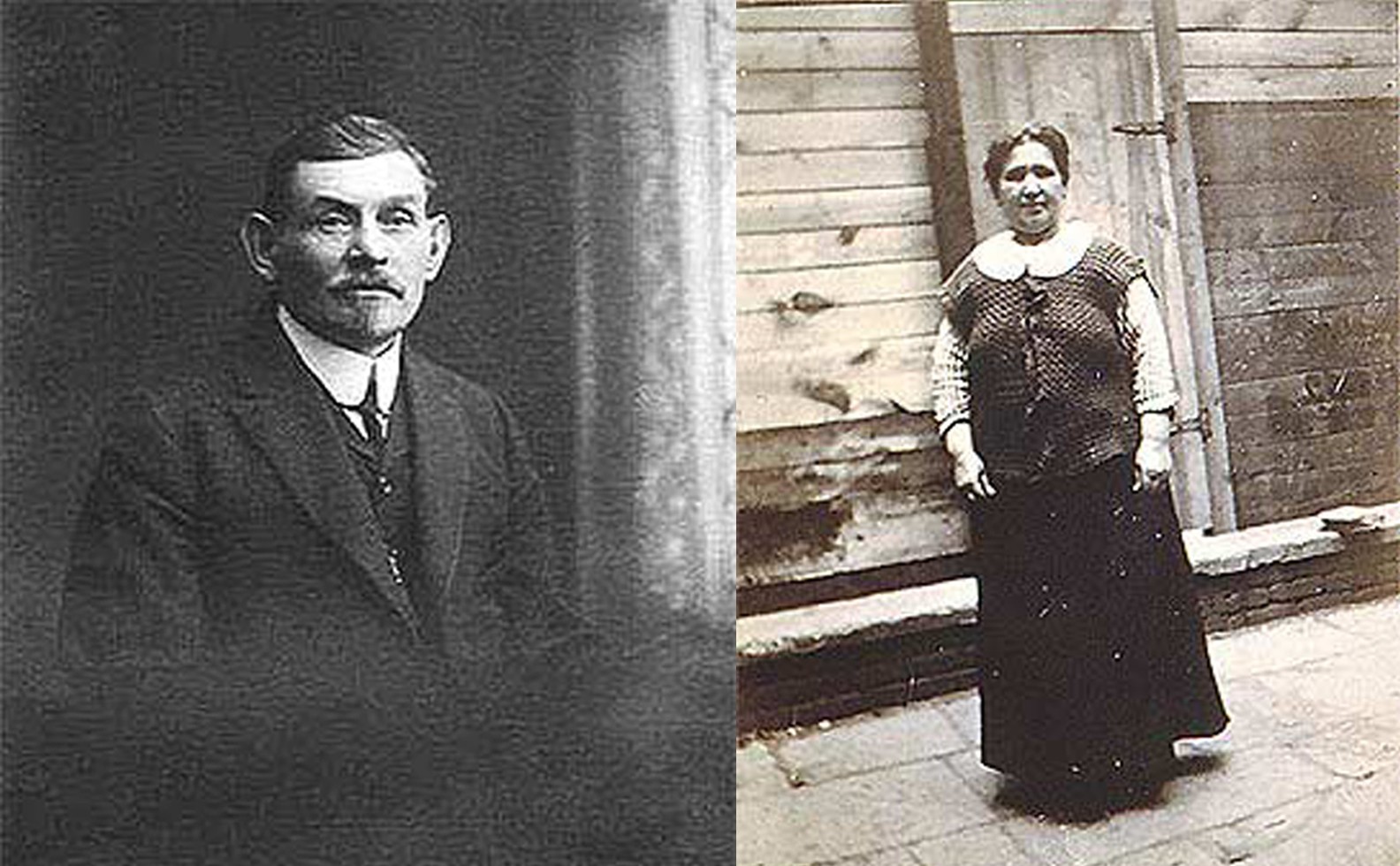

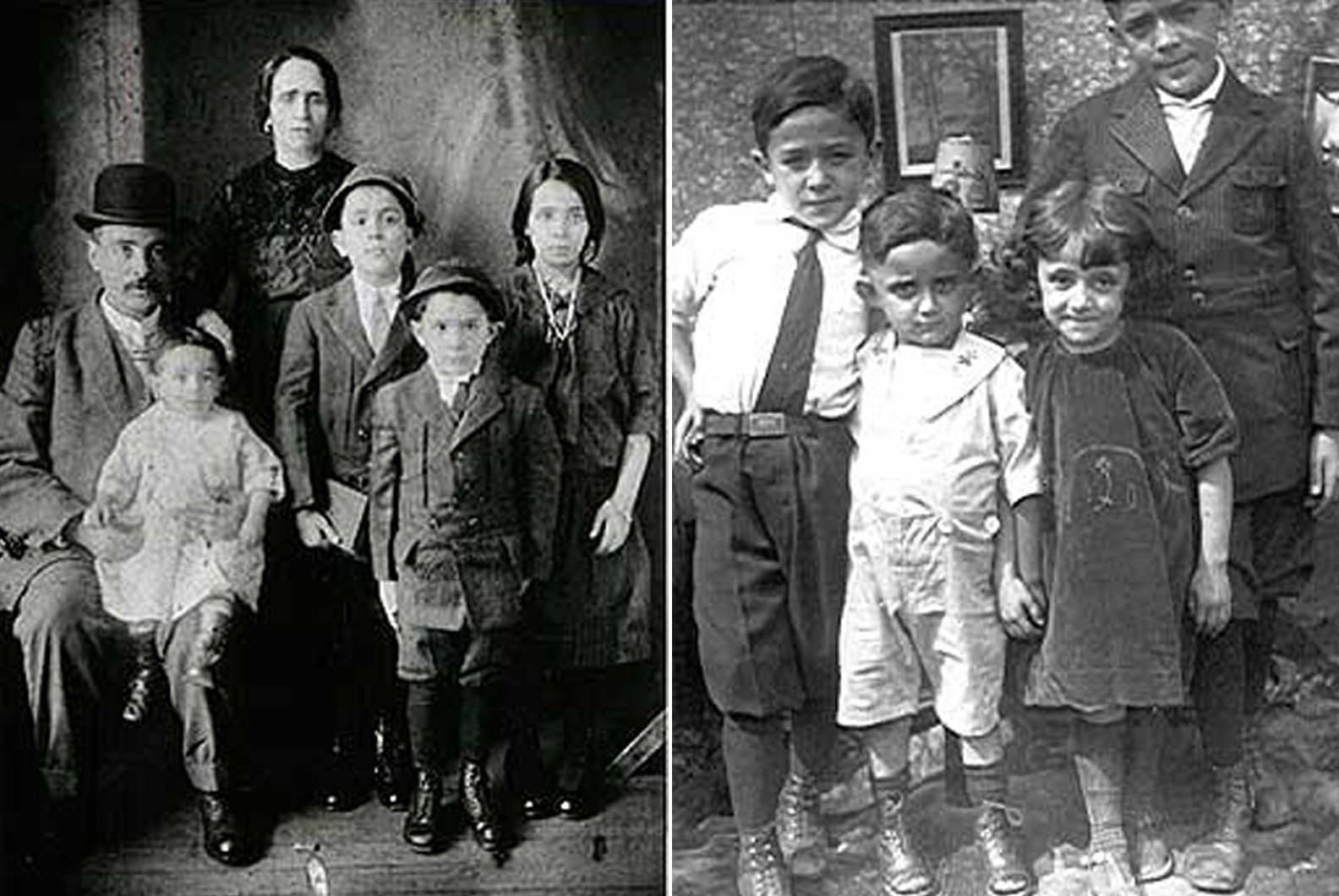

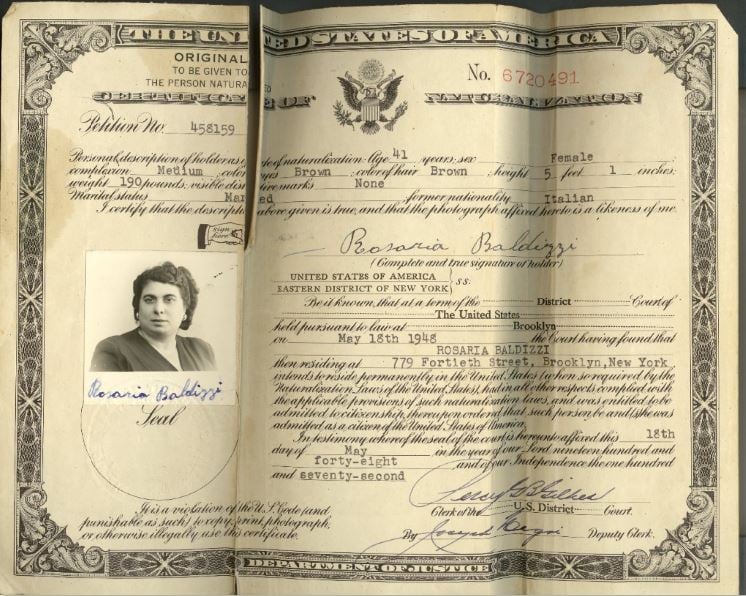

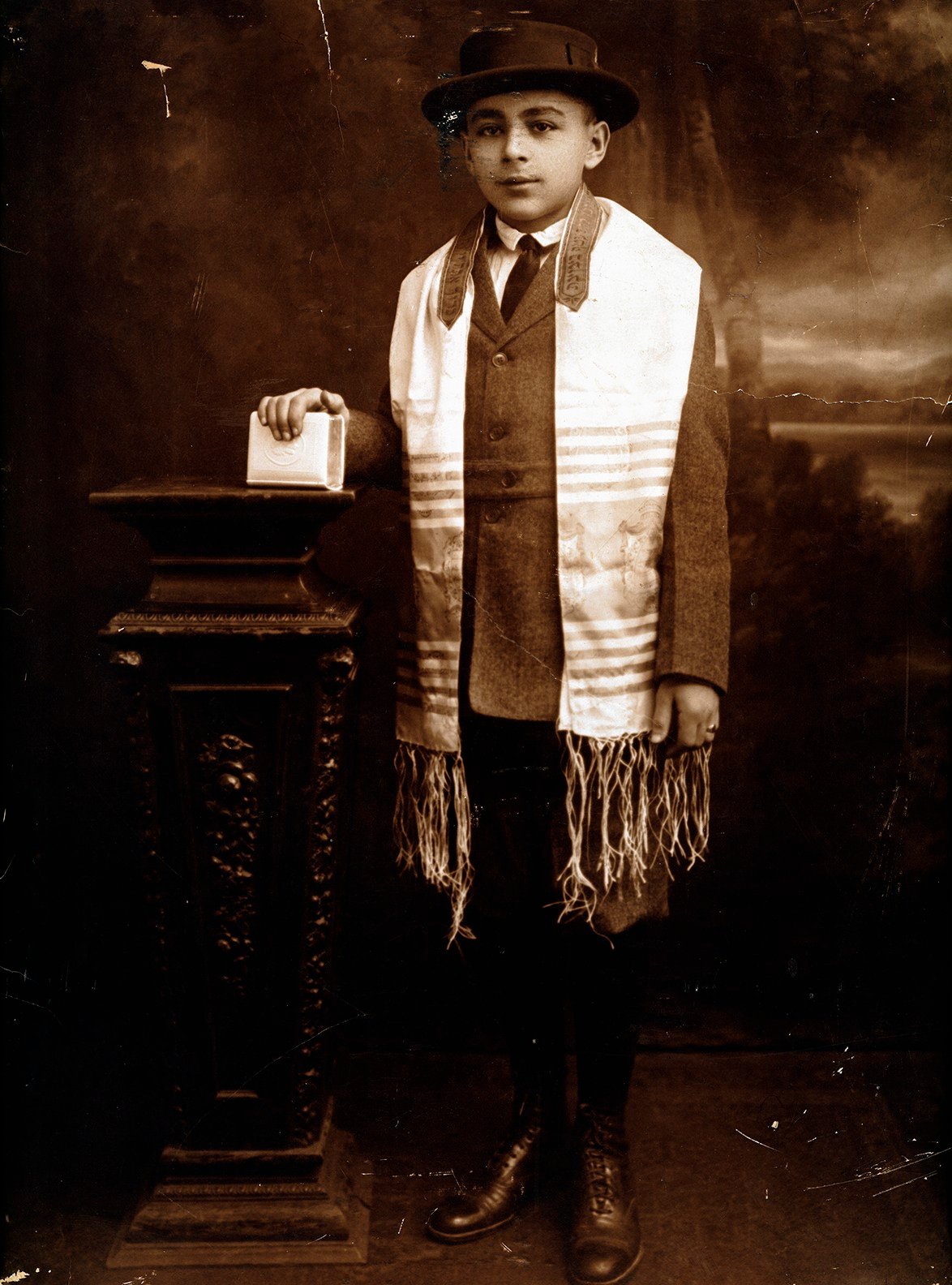

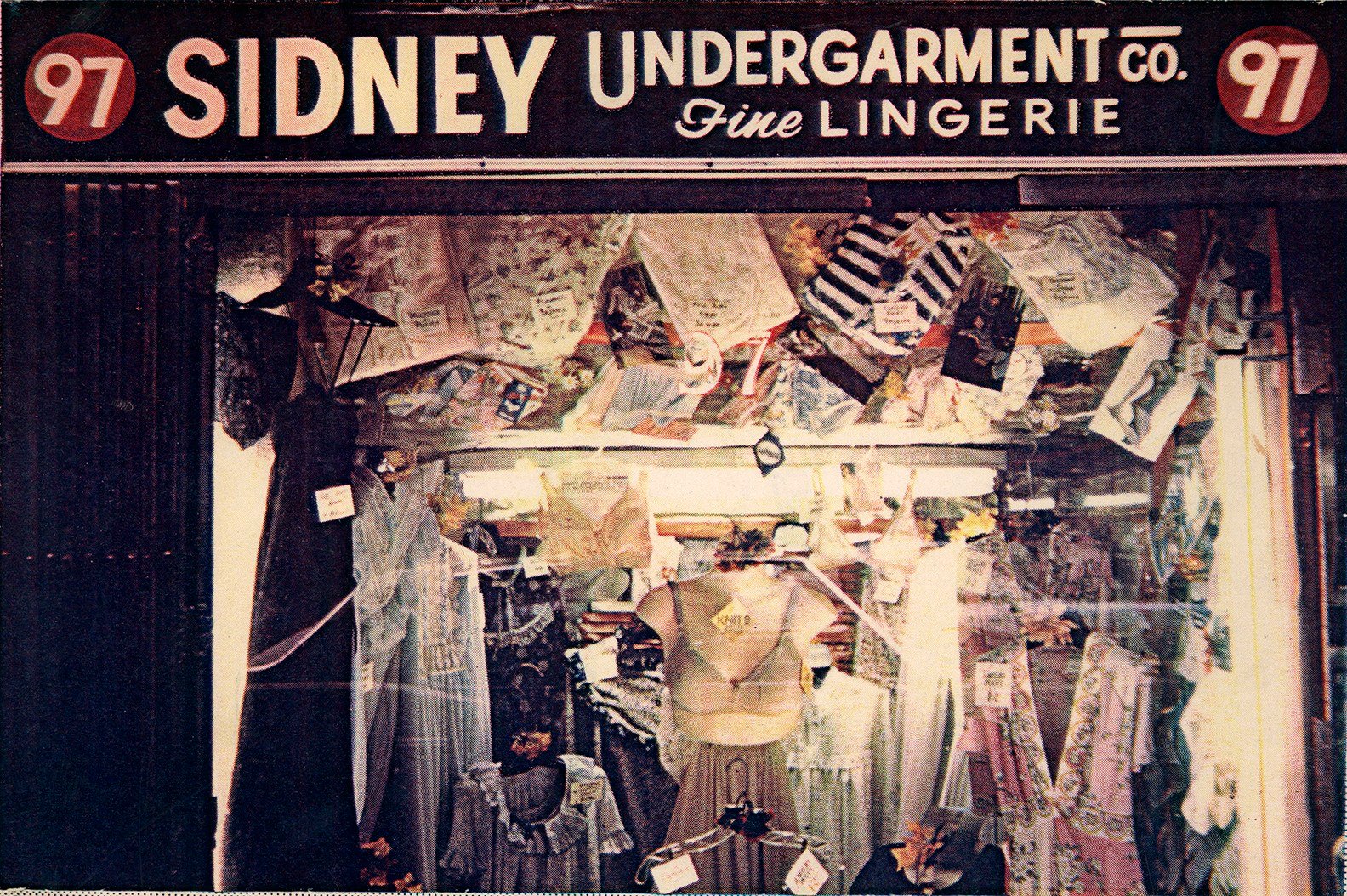

97 Orchard Street is a historic tenement that was home to an estimated 7,000 people from over 20 nations between 1863 and 1935. The five-story tenement was built with 22 apartments, each about 325-square-feet and each consisting of three rooms. Although living in tiny quarters, the families who called 97 Orchard Street home came to America — and New York City’s Lower East Side — in search of a better life and opportunities.

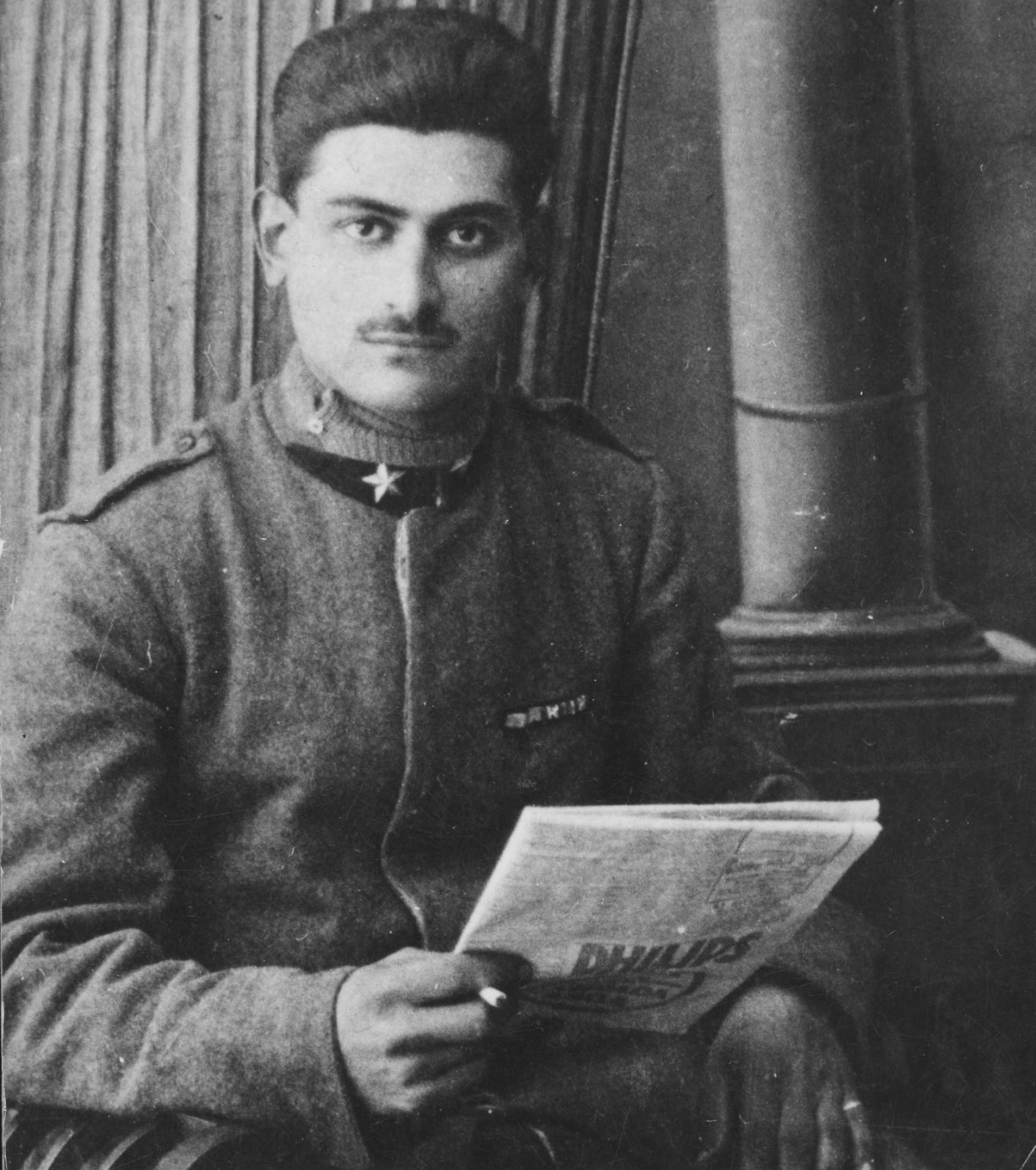

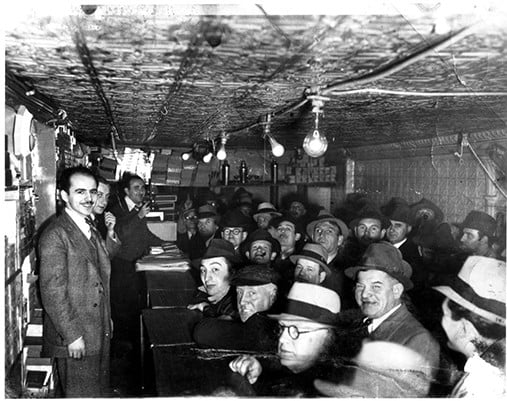

Today, the Tenement Museum has restored seven apartments and a lager beer saloon inside 97 Orchard Street. Demographically, the families who lived at 97 Orchard reflected the trends of immigrant populations in America, from the Northern and Western Europeans of the post-Civil War era of the late 1800s to the Southern and Eastern Europeans of the early 1900s. The Tenement Museum brings these stories to life through its guided tours and programs. Visitors can tour the recreated apartments and saloon to learn the powerful stories of the immigrants who built new lives, weathered hard times, and cleared the path for generations of Americans to come. Their story is our story.