Over the years, the Tenement Museum has collected hundreds of hours of oral histories from former tenants, local business owners, their descendants, and other individuals sharing their own unique immigrant or migrant experience. These oral histories are a way of gathering detailed information that helps us understand a specific time, place, person, or event – shaping our exhibits and our tours. They also guide what aspects of tenement life we research, down to what brand of soap should rest above the kitchen sink. As a storytelling museum, these oral histories are essential to our mission and our efforts to present multiple perspectives of the immigrant and migrant experiences and are an important piece of our collection.

What Gets Remembered

The further back in time we go, the harder it is to find firsthand accounts of the period we want to explore. After finding the Levine family in turn of the 20th century historical records, we began looking for their descendants. In the late 1990s, when the Museum spoke to Harris Levine’s grandchildren, they had only fragmented memories to share. They told us what they could remember, including that their grandfather was a very religious man, who always observed the Sabbath.

These memories help us identify items to furnish the family’s home and interpret other historical documents that provide insight into Jewish daily life and what it meant to run your own business as a Jewish immigrant. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the typical workweek was Monday through Saturday, with Sundays being the day for workers to rest and often attend church. Jews who worked for non-Jewish bosses would usually have to work through the Sabbath, the Jewish day of rest. But because Harris ran his own business, a garment “sweatshop” out of his 97 Orchard Street apartment, he could dictate the schedule, and ensure he (and his Jewish employees) had Saturdays off. Between the memory of descendants and historical records, we can imagine what a Friday night would have looked like in the Levine home. The schedule would have allowed for his wife, Jennie, to prepare a traditional Sabbath meal on Fridays, and his employees to do the same.

In 1988, back when the Museum was first beginning, one way we tried to connect with former residents was through a series of newspaper articles and journal entries. This was how Josephine Baldizzi found us and made her return to 97 Orchard Street in her 60s. She contributed hours of oral history, recollecting her parents’ immigration stories, their 97 Orchard Street neighbors, and details of their day-to-day for the years they lived here.

Some of her more vivid memories were stories of her mother’s cleanliness. In fact, when Josephine first visited her recreated childhood home, a day before it opened to the public, the only aspect she thought we got wrong was how disorderly the room had been laid out, and we had to quickly tidy up. Her mother, Rosaria, was known as “Shine ‘Em Up Sadie” for how clean she kept her home, her clothes, and her kids.

Rosaria challenges the pre-conceived notions of what tenement living was like. Josephine’s memories of her mother help us go beyond the pre-conceived notions of what tenement living was like. We might often think of Jacob Riis’ famous book, How the Other Half Lives, where tenements and their residents were only shown as dirty or in need of help. But from stories like Josephine’s we get a more complicated picture, that tenement homes could be as proudly decorated and beloved as anyone’s home, with flowers in the windowsill and linoleum floors you could probably eat off of. Josephine’s oral history provides a unique perspective on our understandings of the past, and in sharing her memories full of so much detail, such as her mother’s preference for a specific brand of starch, Rosaria becomes a fully realized person, helping people to connect to their past and to their own shared experiences.

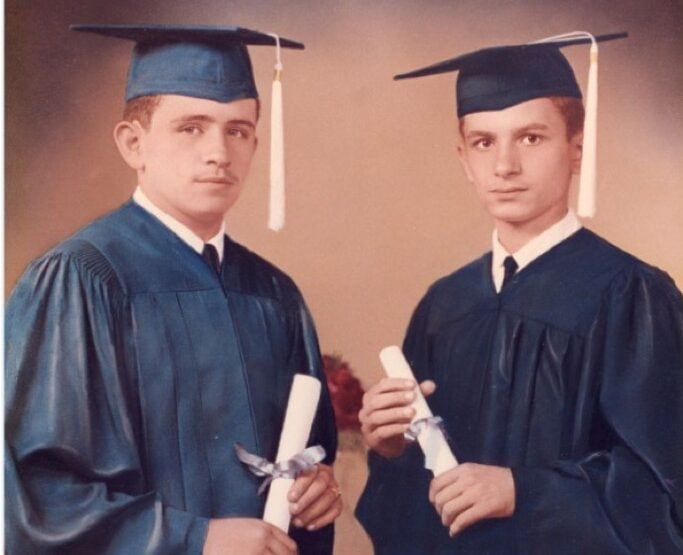

A significant number of our oral histories are from former residents who lived on Orchard Street when they were children. Some of the most vivid accounts come from childhood memories, where the smallest details can create lasting impressions. In developing our exhibit at 103 Orchard Street, we were fortunate enough to collect close to a hundred hours of oral histories, many from former young residents, including the Velez brothers. We spoke with them at length and recorded video interviews with them that we often share directly on our tours. Here is one such example with José:

By holding interviews with multiple family members, we are easily able to corroborate their stories. In this particular example, both Andy and José separately told this story about cooking beans for their mother after school without even knowing the other brother had mentioned it. We then know that this was likely a regular occurrence in their household and that it had an impact on their lives.

This story illustrates the family dynamic and how they were able to work together. It also demonstrates the innovation of their mother, Ramonita, juggling two kids and a job by herself. The task ensured her children came home on time after school by the state of the beans left on the stove when she came home from work. It also informed how we laid out their recreated kitchen, with Ramonita’s favorite spices on the spice rack and a bean pot left on the stove. Like Josephine’s stories of growing up in 97 Orchard Street, the Velez brothers have strong memories of spending time in the kitchen – so much so that when we invited them back to 103 Orchard Street in 2017 to preview the exhibit of their childhood home, they spent much of the time just standing in the recreated kitchen, reminiscing about the past.

Explore the recreated kitchen of the Saez Velez family below. Click on the (+) buttons for details. For best results, view in fullscreen by clicking the “fullscreen” button in the top right corner.