Blog Archive

Adapting to America

Adaptation is one of the themes that come up most often during our tours here at the Museum—and it will be a key topic at tomorrow’s free Tenement Talk with New York Times journalist Kirk Semple. We hope you can join us! To get the conversation started, we’re taking a look at the history of assimilation & adaptation.

The U.S. has long been called a “melting pot,” in which people of different cultures come together into a cohesive whole, but the metaphor is a problematic one. It suggests that cultural difference is something to be avoided, and even overcome. The “melting pot” metaphor brings up some important questions on our tours: Should immigrants and their descendants maintain their cultural roots? How can we balance our individual identities with participation in American life? How does the process of adapting to America today differ from the experience a century ago?

Cover of "The Melting Pot" play, 1916. From the Library of Congress and University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections Department.

Dating to 1782, J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur’s Letters from an American Farmer contains American literature’s first recorded use of the concept of immigrants “melting” into the receiving culture. He wrote that America is a place where “individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labors and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world.”

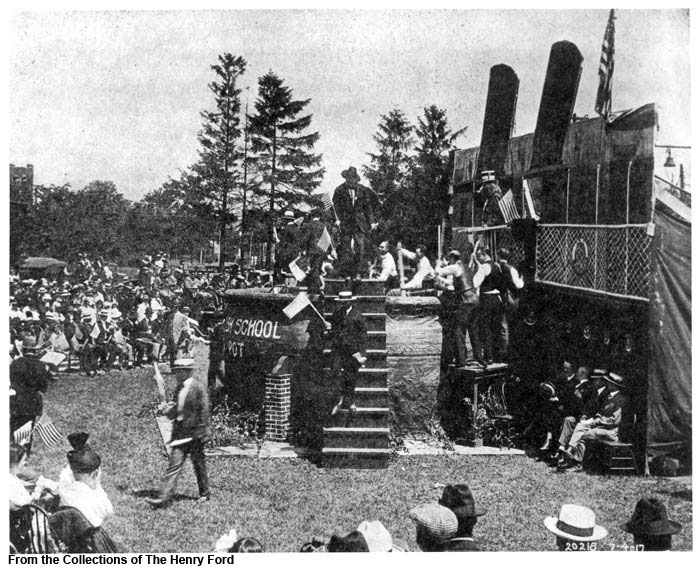

Automobile magnate Henry Ford not only firmly believed in the virtues of the melting pot—he literally, and bizarrely, built one. In the 1920s, Ford required his immigrant workers to attend lengthy “Americanization” courses. The graduation ceremony from this program culminated in a pageant in which workers clad in outlandish versions of their “native” costumes descended into a giant pot—a twenty-foot-tall crucible made of wood, canvas, and papier-mâché—and emerged on the other side wearing modern business suits, waving tiny American flags, and singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The “melting pot” at Henry Ford’s Americanization School. From the “Automobile in American Life” online exhibit, University of Michigan-Dearborn, and the collections of The Henry Ford.

Ford hoped that his physical demonstration of the melting pot would, as he put it, “impress upon these men that they are, or should be, Americans, and that former racial, national, and linguistic differences are to be forgotten.” (Based on investigations into their home lives, Ford employees who failed to uphold his standards found they could also forget about keeping their jobs.)

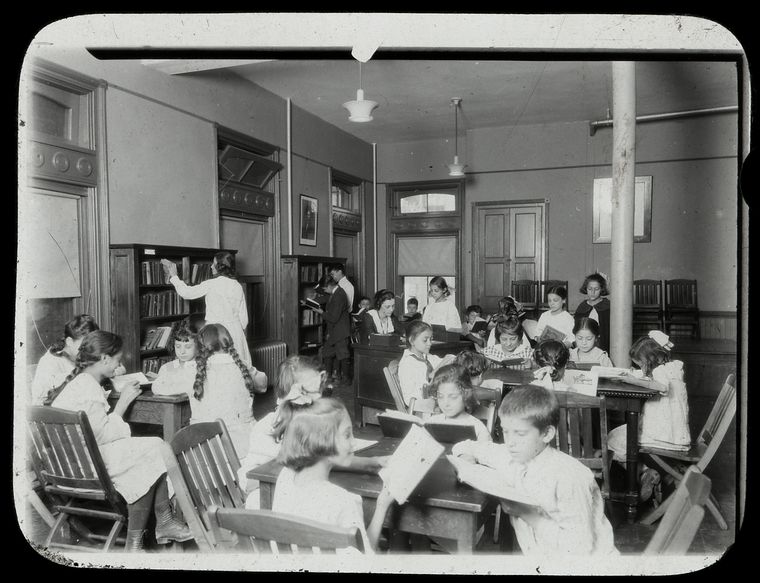

A different assimilation strategy could be found in the American settlement house movement. Settlement houses were privately-funded social service agencies staffed mostly by wealthier, native-born Americans who believed they were working toward the general welfare of immigrants, and the larger society, by bringing each immigrant group into mainstream America.

These organizations provided health and employment services, cooking classes, education and after-school recreation for children. Families who lived in our tenement building at 97 Orchard Street might have seen settlement houses as a gateway into American life. Today, the University Settlement, Henry Street Settlement, and Educational Alliance, among others, continue to deliver a wide range of social services and creative programs to tens of thousands of New Yorkers each year.

Children reading in the Mulberry Settlement House library, 1920. Image courtesy the New York Public Library.

Tomorrow’s Tenement Talk will focus on a more recently founded program: The Refugee Youth Summer Academy. The Academy helps youth find footing and prepare for school over the course of the six-week program of academic coursework, creative-arts classes, and field trips. In his 2012 New York Times article, “In New York, With 6 Weeks to Adapt to America,” Kirk Semple wrote of that year’s Academy enrollees:

“They hailed from at least 13 countries, including Nepal, Burkina Faso, Iran, Iraq and Cameroon. Some had been in the country for a couple of years… They spoke at least 17 native languages. Some could speak and read English fluently; others could not write their own name in any language. Some had attended school in their home countries; others had never been in a classroom. If there was any commonality in their experience, it was that their families had been driven from their homelands and were seeking a better life in the United States.”

At our Tenement Talk Semple will lead a panel discussion with The Refugee Youth Summer Academy principal, an upper-elementary school teacher, and a student leader. We hope you’ll join us for this moving program, looking at what adaptation means for some of America’s newest, young arrivals.

—Posted by Lokki Chan and Amanda Murray