Blog Archive

The Gunfight at Rivington Street

On a warm Tuesday night in 1903, the Levine family was most likely settling in for a much-needed night’s rest. If you’ve taken our “Sweatshop Workers” tour, you’ll know that Harris Levine ran a sweatshop out of his tiny apartment at 97 Orchard Street. His wife, Jenny, spent her long days cooking, cleaning, and caring for their five children, one of whom, Fay, had only just recently been born. This is a family that needed their sleep, but one can imagine that on the night of September 15, 1903, their dreams were interrupted by the thunderous sound of gunfire and destruction only a block away.

For on Rivington Street and Allen Street, a bloody gang shootout was in full-swing between the Lower East Side’s Eastman Gang and the rival Five Points Gang. The battle lasted for hours, a culmination of conflict between the two gangs over territory and criminal opportunities. There’s no doubt that, if Harris and Jenny were jarred awake that night, they would have known exactly who was causing all that trouble.

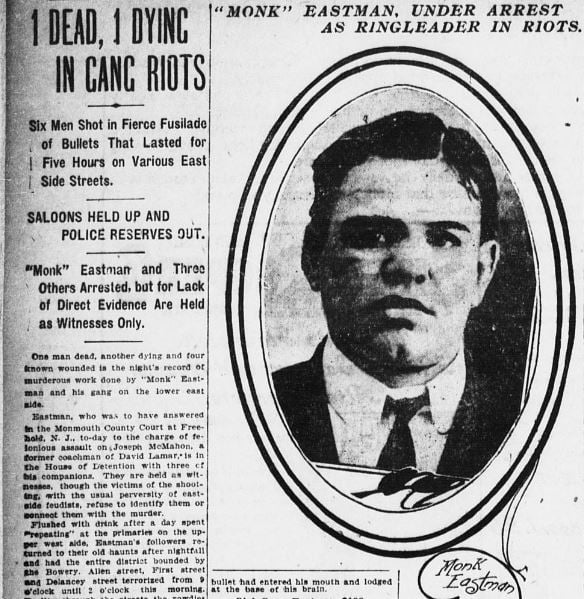

Edward “Monk” Eastman ran his Jewish-American gang beginning in the 1890s. The 1,200 or so “Eastmans” ran brothels, protection rackets, and drug rings on the Lower East Side, as well as murder-for-hire. They were associated with the corrupt politicians at Tammany Hall, who would turn a blind eye to their criminal activities in exchange for their services.

The Five Points Gang was run by an Italian-American named Paul Kelly, formed out of the remnants of earlier 19th century gangs like the Dead Rabbits and the Whyos. They were an army of about 1,500, entrenched in robberies, racketeering, prostitution rings, and also worked as strong-arm men for Tammany Hall. When they finally waned in 1910, they helped train the next generation of mob bosses, such as Johnny Torrio, Lucky Luciano, and Al Capone.

September 15th was a hot day, a busy day. It was Election Day, and a ceasefire had been issued across New York City. Both gangs had been instructed by Tammany Hall to help secure their votes, by whatever means necessary. This typically entailed intimidation and voter fraud – submitting voting slips for people who didn’t exist, or who weren’t able to vote.

After fulfilling their “civic duty”, these Bowery toughs were looking to unwind. The first fight started when about 40 of Eastman’s men entered Livingston’s saloon on 1st Avenue and 1st Street. Immediately, they got into altercations with some men already inside, resulting in one man, Anton Bernhauer, being shot through both cheeks by an Eastman gang member. According to The Evening World paper which came out the following day, Bernhauer had been trying to leave when he’d caught the bullet, and had been “spitting out his teeth as he ran” all the way to the Bellevue Hospital.

The fighting spilled out into the streets and over blocks, fueled by previous aggressions and probably a lot of liquor. The worst occurred just before midnight, when about six members of the Eastman gang stumbled upon an equal number of Five Pointers, getting ready to rob an Eastman-run card game beneath the elevated subway on Allen Street.

Beneath the Allen St. subway, by Berenice Abbott

Nowadays, Allen Street is a flowery, sunny, wide street with winding bike and pedestrian paths, and benches and tables to stop and take it all in. But in 1903, Allen was known as “the street of perpetual shadow,” both because of the constant darkness beneath the elevated railroad tracks and for all the crime and prostitution that went on there.

As soon as the gangs saw each other, weapons were drawn and the firefight began, shots firing indiscriminately. More gangsters hightailed it to the battle, so that by the time the first cops tried to intervene, there were roughly fifty men all shooting at each other (though they did take a quick break to shoot at the first two cops instead). The gangs had turned out the streetlamps, and in the shadows the only lights were the sparks of bullets ricocheting off the ironworks.

By midnight, the number had raised to 100 gang members, firing at each other beneath the train tracks and stretching out over several blocks. At one point, Monk Eastman himself arrived and began directing the shooting like an army officer (some foreshadowing, as Monk would later enlist in the armed forces and become something of a war hero during WWI), and though Paul Kelly had not been recorded as being there, it’s unlikely that he’d miss such an event. Finally, reserves from several police stations arrived, banded together like an army themselves, and stormed Rivington Street. For a good fifteen minutes, there was nothing but the sound of shooting. Men were even reported on the rooftops, throwing bricks down at police officers.

Eventually, the gang members dispersed and only a few were arrested, including Monk Eastman. He claimed he’d just been a bystander passing through, and with no one willing to bear witness to the event, he was set free, along with most of the other members of his gang. In the end, only two men died from the event, both Five Pointers: John Carroll, who was shot by a detective, and Michael Donovan, who had been shot in the stomach and refused to identify the man who shot him, saying, “I know who shot me, and when I get out, I’ll fix em.” Several more were injured, including one of Eastman’s chief lieutenants, George “Lolly” Meyers. Meyers had been one of the few arrested, and hadn’t said anything about the bullets lodged in both legs as he was moved around from place to place and examined by policemen and lawyers. His injuries were only discovered a full 24-hours later, when the pain was too much for him to bear silently any longer.

The next morning, the residents of the Lower East Side, including the Levines, could see the evidence of the night’s previous battle. Many of the windows of nearby tenements had been broken, and there was clear damage to the ironworks of the subway track and to the trains that ran overhead as the fighting went on. Public outrage over the incident made it difficult for politicians to keep turning a blind eye to the goings-on of their criminal allies, and a city-wide crackdown was issued against all gang members, including the Eastmans and the Five Pointers. But crime never truly lessened because of it, and when the Levines finally moved out of 97 Orchard the following year, the safety of their family was likely one crucial factor to finding a new home.

Rivington and Allen Streets in 2017

- Post by Gemma Solomons, Marketing & Communications Coordinator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum