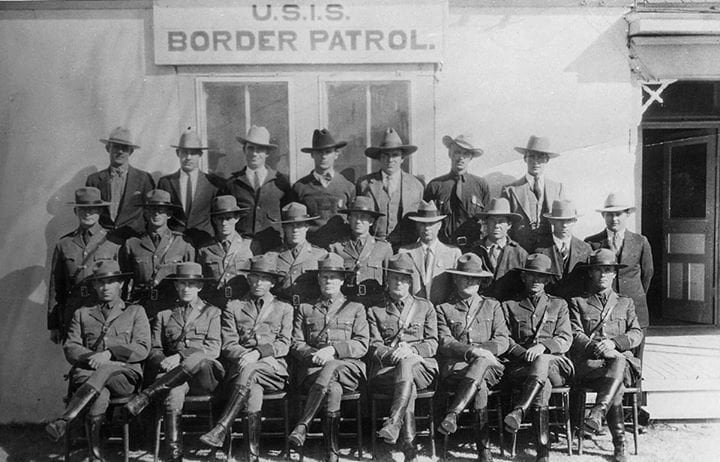

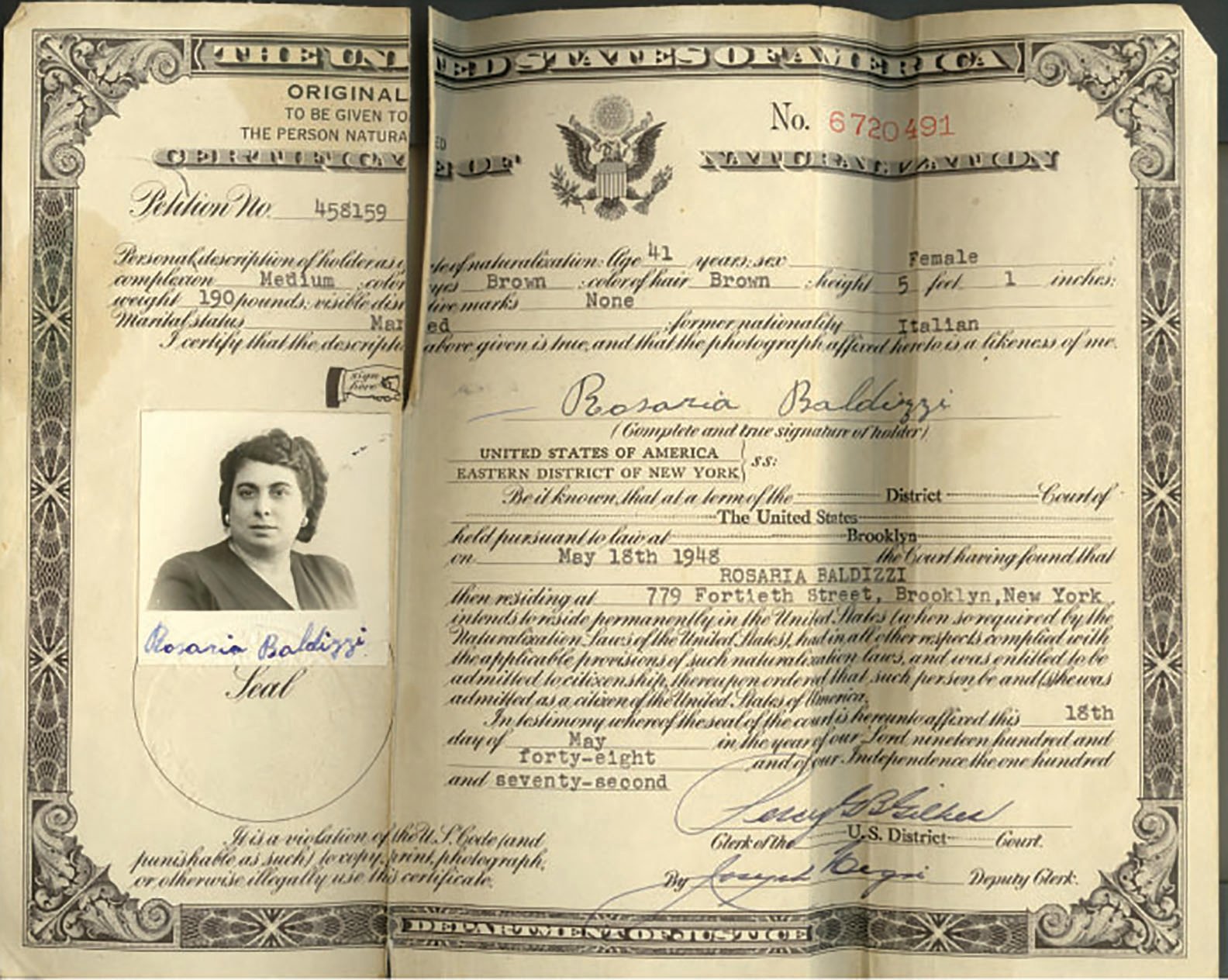

On May 26, 1924, the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act was enacted in the United States, essentially creating a new possible status for immigrants: “undocumented.” Passing in Congress with limited opposition, it was the most comprehensive immigration restriction to date, and the first to explicitly exclude Europeans.

The law introduced a quota system, limiting overall the number of people allowed to immigrate per year to 165,00, and 80% reduction from prior years, and allotting a certain number of visas to people from each country outside of the Western Hemisphere. Despite the law passing in 1924, they decided to use the “national origin” statistics from the 1890 census as a benchmark for the quotas, a decision that deeply restricted Southern and Eastern European immigrants. In 1890, the majority of immigrants were coming from Northern and Western European countries like Britain, Germany, and Ireland, and the numbers of non-Western European immigrants were much lower than in later censuses. As an example of how this law affected people in non-Western Europe, in 1921 a recorded 222,260 Italians were able to immigrate to the United States. By 1925, there were only 6,203 Italians who obtained visas through the new system.