Spring has arrived, but covid-19 has changed our relationship with the outdoors.

Great Reads, New York City Architecture

Where the City Kids Play

May 15, 2020

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. "Girl'S May-Pole, Seward Park." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1890.

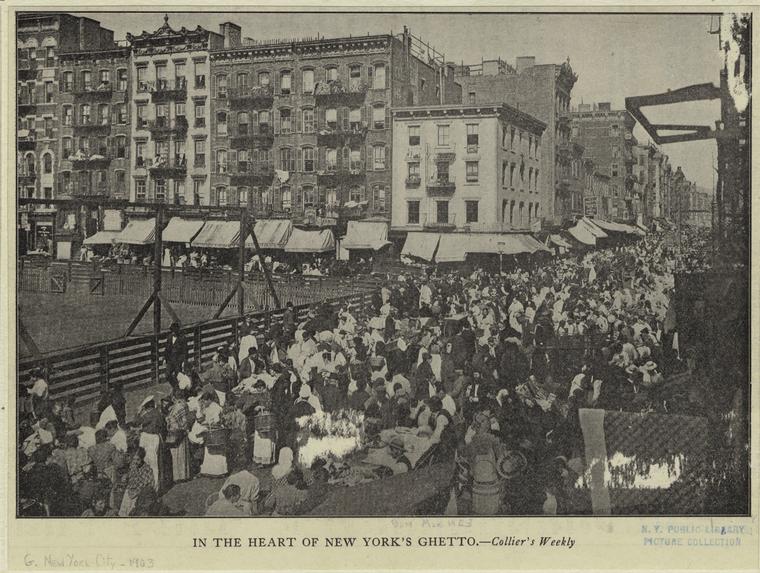

From the closure of city playgrounds, to the efforts to open miles of streets for pedestrians, the City has been navigating how to manage outdoor space during an unprecedented challenge. In a city where space is at a premium, finding areas for children to play is not a new conversation, and it’s one that took root on the Lower East Side (LES) over a century ago.

By 1900, the LES was one of the most densely populated neighborhoods on earth, with over 300,000 people living in a square mile. Children played games in cramped hallways, tenement rooftops, or between carriages and pushcarts in the streets. Many reformers and social activists felt that change was needed, and pushed for parks and playgrounds.

The Outdoor Recreation League, an advocacy group created by Charles B. Stover and Lillian Wald, founders of University Settlement and Henry Street Settlement, respectively opened Seward Park in 1899 at Canal and Essex street. The main mission of the ORL was to provide organized play spaces and recreational enrichment for neighborhood children, while encouraging the City to invest in building and maintaining parks and playgrounds. By 1902 the Parks Department assumed control of Seward Park. Within the next year, the first municipally built playground in the country opened on the site.

When designing Seward Park, reformers grappled with how to bridge the gap between an urban childhood and a rural one. Many reformers felt that the “ideal” childhood was one surrounded by greenery and open sky in the pastoral countryside, rather than playing stickball and kick-the-can on city streets. Proponents of playgrounds had different ideas about creating the best public recreation space. The compromise was a playground within a park.

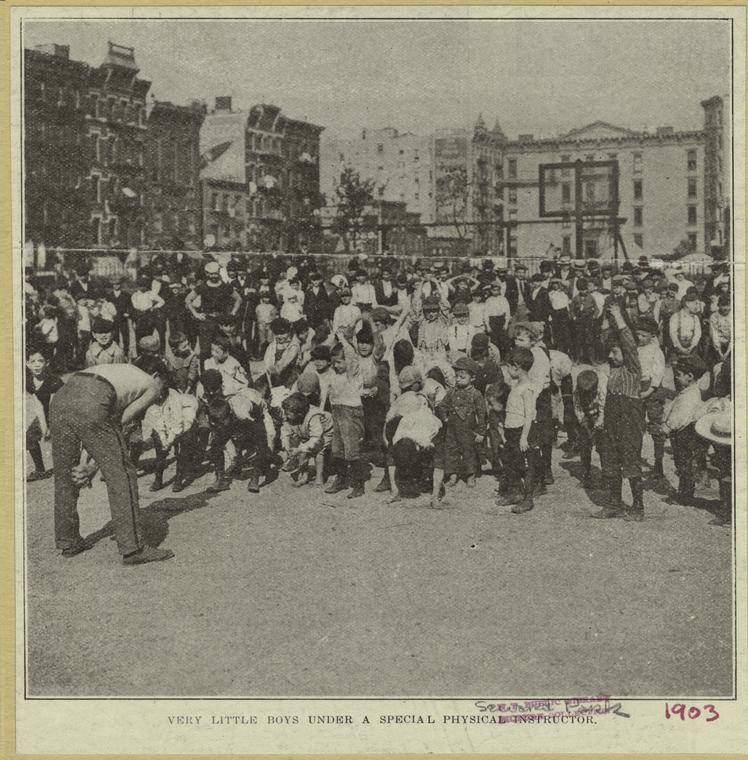

The Park featured a gymnasium equipped with athletic apparatus, from punching bags to croquet courts. The free bathhouse proved so popular it was open as late as 11pm. A “Mother’s Corner” was also part of the design, with rocking chairs for parents to sit with their infants.

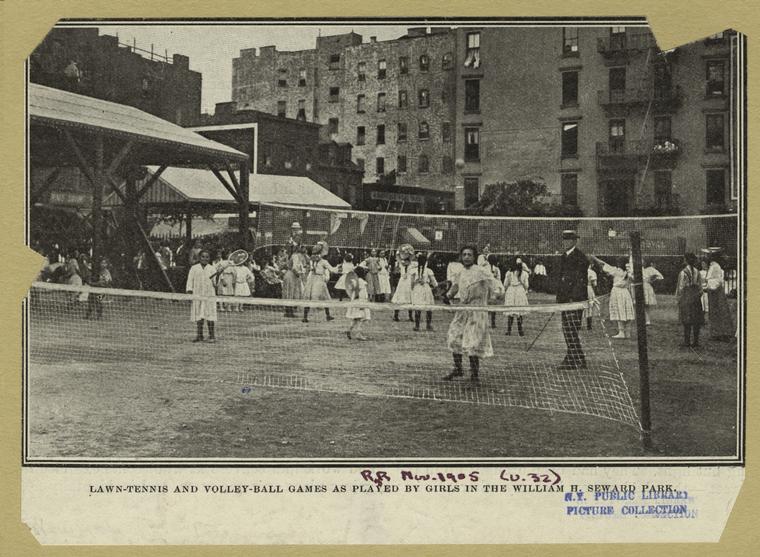

Notions around play being gendered led to separate playgrounds for boys and girls. The boys’ playground hosted sports such as football, basketball, baseball, and tennis, with formalized teams playing competitive inter-park matches.

The girls’ playground featured a space for match games, though only for tennis, volleyball, and tether ball. There were also croquet courts, sand pits, and baby swings, as well as a kindergarten pavilion for unstructured play.

All of these activities were contained within an imposing six-foot fence.

Parks were thought to be something separate from the city, a structured container for the “ideal” childhood to lead to successful adulthood. Today, those attitudes have changed. In 2019 Seward Park underwent an extensive redesign through a Parks Department project called Parks Without Borders.

Parks Without Borders is an initiative that seeks to make parks feel cohesive and welcoming. Through community input and the advocacy of the Seward Park Conservancy, Seward Park was voted by residents as most in need of this update and became the first of eight parks completed by the project in December 2019. It took $6 million and nine months to bring in the new features. The fences were lowered, the park received a new lawn and garden, new exercise equipment, and a paved courtyard outside of Seward Park Library, creating new space for programs and activities.

While the mindsets shaping parkland have changed, their importance as anchors for their communities has remained. As the weather warms, and you take a socially-distanced stroll through a city park, think about how they came to be, and the community support that allows them to continue and grow today.

Written by SJ Costello, Tenement Museum Lead Educator

Sources:

https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/timeline/playgrounds-public-recreation

Warsh, Marie. Cultivating Citizens: The Children’s School Farm in New York City, 1902–1931. Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Vol. 18, No 1. (SPRING, 2011)

Department of Parks Report for 1902 (part 1). (1903) New York, NY: Martin B. Brown Co. Printers and Stationers.

Department of Parks Report for 1904. (1905) New York, NY: Martin B. Brown Co. Printers and Stationers.

Department of Parks Report for 1905. (1906) New York, NY: Martin B. Brown Co. Printers and Stationers.

https://www.nycgovparks.org/planning-and-building/planning/parks-without-borders