Along the western edge of the Lower East Side, bound by Chrystie and Forsyth Streets there currently stands a seven block stretch of open park space. Surrounded by a fence in the very heart of that park, between Delancey and Rivington Streets, a lush community garden rises up from the surrounding brick and cement. And on most fair-weather days, beside the gate sits an older African American man with watchful knowing eyes look out from under the visor of a Yankees baseball cap. The name of the park is Sara Delano Roosevelt, the name of the garden is M’Finda Kalunga, and the name of the man is Robert Humber- though he is known far and wide as Bob. From the garden gate Bob spends his time catching up with friends, making arrangements to attend community meetings, offering food and clothes to the homeless of Lower East Side, and listening to (alongside sharing) on-going concerns about the Park. Bob’s roots as an activist stretch back nearly 50 years. Indeed, he was the catalyst for both creating M’Finda Kalunga Garden and transforming Sarah D.

Behind The Scenes, Resident Feature

At the Crossroads: A Portrait of 8 New York City Blocks and One Man

February 20, 2020

Reform: From Tenements to Parks

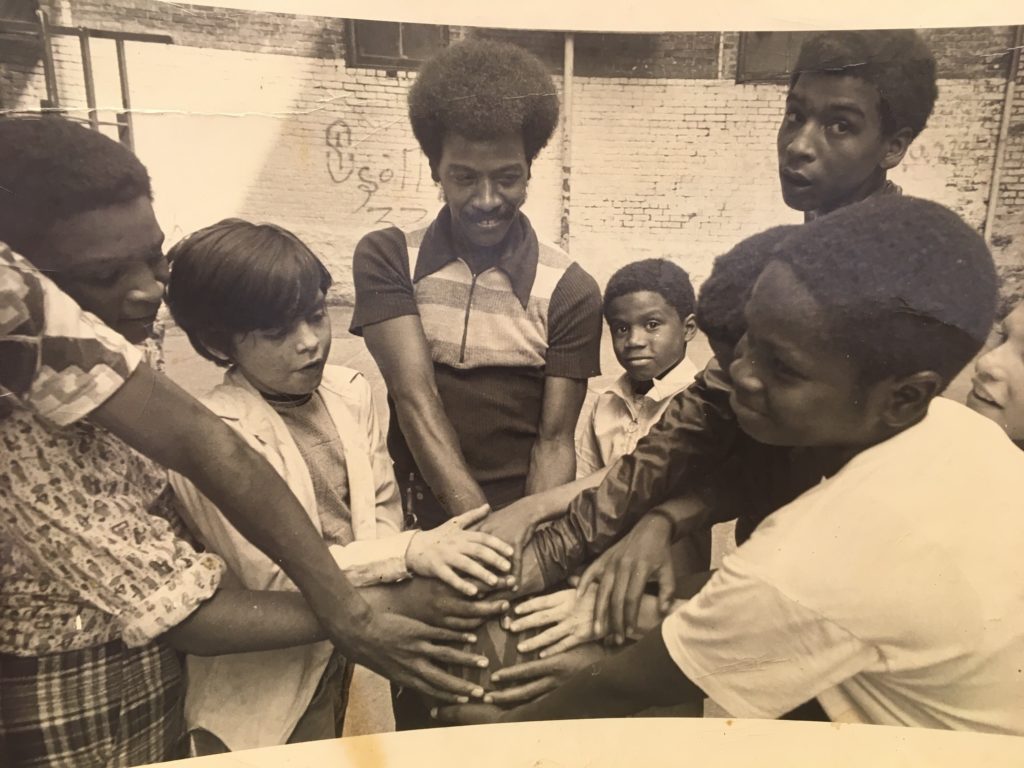

No trace of what came before remains, but in the decades prior to Bob’s time, the land between Chrystie and Forsyth Streets was crowded with old tenement houses. The southernmost block between Canal, Bayard, Chrystie, and Forsyth enjoyed a brief moment in the limelight as a part of the 1900 Tenement Exhibition. A three-dimensional model of this block was fabricated and displayed beside grim statistics about the sanitary concerns and antiquated tenement living conditions. The great advocate for tenement reform, Jacob Riis remarked, “In its gloom and its crowds, it is typical of all the rest on that East Side, where the population is jammed as nowhere else in the world.”1

Image Left: Tenement House Model, Tenement House Exhibition, 1900

The entire purpose of the Tenement House Exhibition was to inspire change and improve the lives of New York City residents, and in this, it was successful. In 1901 New York City passed the Tenement House Act which not only established standards for new housing, but also created a minimum standard of living for all older apartment houses. This meant landlords of Pre and Old Law tenements were mandated by law to upgrade their properties, offering increased access to air, light and running water. While landlords broadly resented and bitterly contested this law, after 1905, they had little choice but to capitulate and so life improved, albeit marginally, for the renters across New York City. (Ironically, whatever reforms were made to the tenements featured in the Tenement House Exhibition model were short lived- the entire block was raised as a consequence of completing the Manhattan Bridge.)

Reforms aside, the old tenement houses of the Lower East Side seemed to be frozen in time as new building projects and technology continued at a steady pace around them. Moreover, the restrictive changes in immigration law that culminated with the passage of the National Origins Act in 1924 transformed this once densely crowded section of the city into an area of widespread vacancy. Landlords were struggling to maintain their aged tenement properties with fewer newcomers arriving to rent them to. City planners, however, saw the Lower East Side as an opportune place for large scale urban renewal projects.

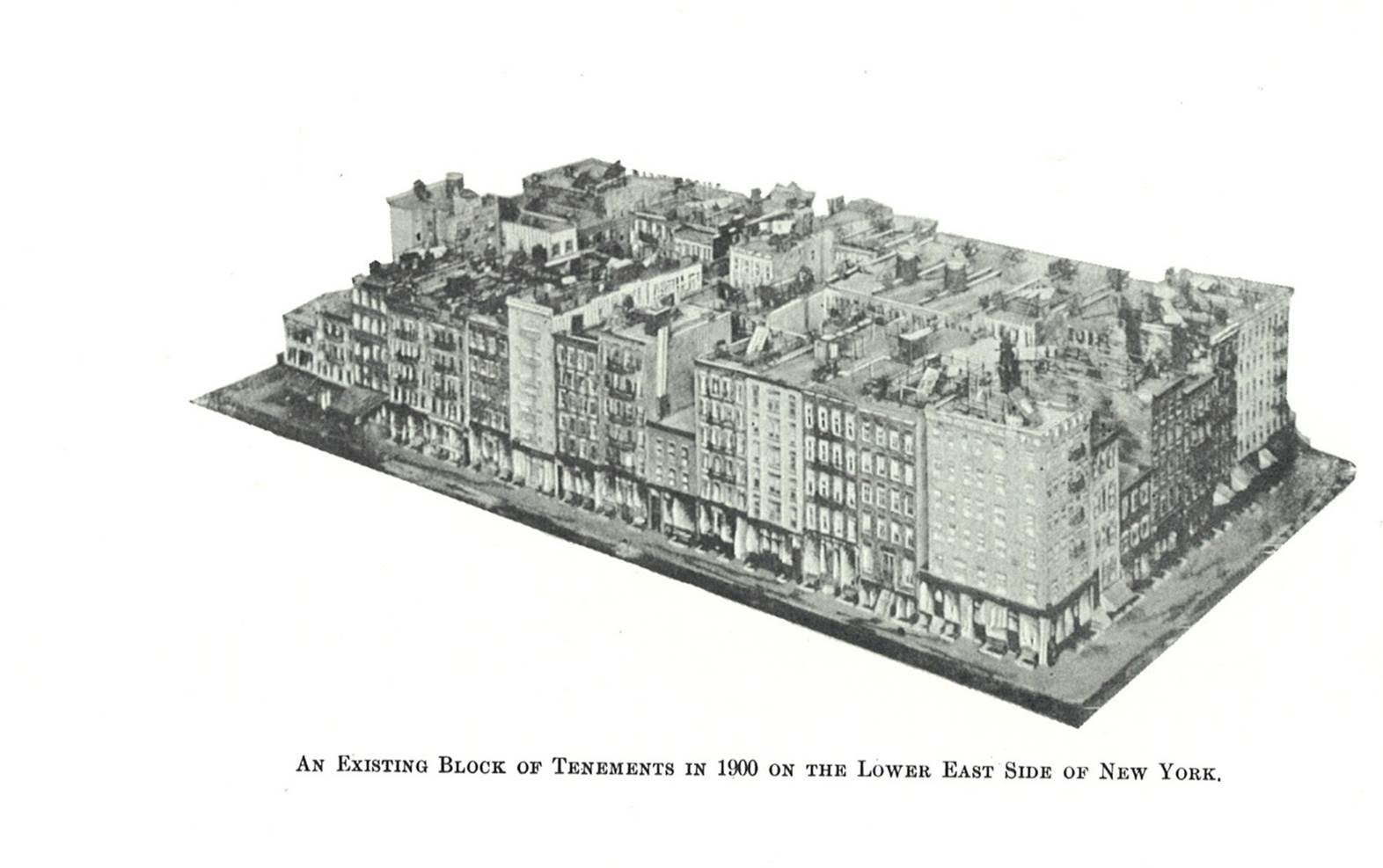

With the objective to expedite traffic between the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges, planners targeted the seven remaining blocks bounded by Chrystie, Forsyth, Canal and Houston. Their plans for this tract of land involved widening both Chrystie and Forsyth Streets and required the demolition of every building across these seven blocks. What remained, labeled ‘excess condemnation’2 was set aside for an ambitious model housing development. The timing of this project, however, could not have been worse since it coincided with the stock market crash of 1929. By December 1930, as the nation plunged into Depression, 200 tenement houses were raised displacing upwards of 4000 people3. Oddly enough, the sprawling field of rubble stretching north to Houston from Canal represented a brighter future for housing the Lower East Side (perhaps excluding the people who were forced to move).

Image Right: ‘Where Model Homes Will Rise on East Side’, New York Times December 7. 1930

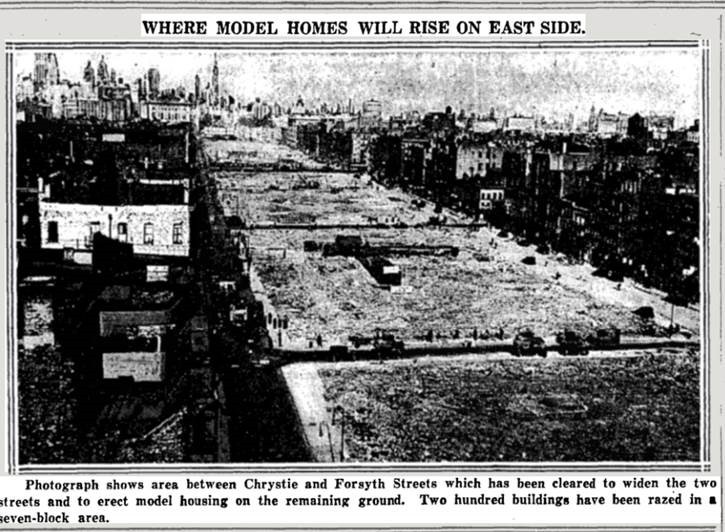

As optimistic as people were at the outset of this model housing project, their enthusiasm for it dimmed with each of the many delays and bureaucratic hurdles. Ultimately the area of ‘excess condemnation’ from which the model homes were supposed to rise, was leveled off, paved over, and remained thus for over two years. For a brief moment, in spring of 1932, new life was breathed into the promised model homes. The Department of Commerce announced that the architectural firm of Howe and Lescaze’s model housing plan was approved for construction.

Across New York City, imaginations were inspired by the designs for the proposed 24 buildings. Such amenities as elevator access, roof terraces (“to be available for recreation as well as for hanging out wash”4), seemed like a dream to people accustomed to walk-ups. Most radical of all, the buildings were held aloft from the ground level by 14-foot pillars allowing for play and leisure space during inclement weather. The proposal offered “a brighter outlook on life and a cheerful environment for a new community of about 8,000 persons” available for a monthly rent of $10.95 per room.5

Despite the collective desire to see this dream housing come to fruition, the seven blocks remained dormant for another two years, until finally in February of 1934, a newly elected Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia officially put an end to the project. Pointing to the corruption of the previous administration and blaming it for the City’s failure to erect model housing, LaGuardia went further to claim that the land itself was ‘unsuitable’ for such a project. He proposed, instead, a park and playground and appointed Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses, to oversee the project.6

Image Left: Houses on Stilts, Howe and Lescaze model houses, Shelter April 1932

People who had lost all hope of the model housing project enthusiastically embraced the plans for a park on the Lower East Side. The only opposition came from Borough President, Samuel Levy, who argued against closing east/west cross streets. Moses proceeded to implement his plan, dismissing Levy’s objection asserting that, “You can’t have a decent park or playground with a cross street running through it every 200 feet”7. On September 12, 1934, the Department of Parks held an opening ceremony for the park, despite it being only two thirds completed. Mayor LaGuardia delivered an address and dedicated the park to Sara D. Roosevelt, president Franklin Roosevelt’s mother.

Image Above: Sara Delano Roosevelt Park looking South from Rivington and Chrystie, 1935.

The finished park represented both a sense of closure and a hopeful new beginning for the Lower East Side. Initially, there was great enthusiasm for the park. The local Settlement Houses took advantage of it for their summer programs, local clubs scheduled parties, plays, musical performances and gatherings.8 For a period there was a feeling of rebirth on the Lower East Side- especially for the children who had limited access to safe park spaces for play.

Revolution: Decline and Rebirth

However, over the next three decades the combination of deindustrialization, disinvestment, and fiscal crisis contributed to the decline of Sara D. Roosevelt Park. By the mid 1960’s, SDR Park became synonymous with poverty and homelessness, vandalism, gang violence, and drug and sex trafficking. It was also during this period that Bob moved to the Lower East Side. Like the Park he now protects, Bob’s story has deep roots, and in early 2020, he shared that story with the Museum.

Robert Humber was born in Georgia, USA on June 12, 1936 to a Panamanian father and Georgia-born mother. Like many African Americans living in the South during this period, Bob’s father set his sights on moving to a northern city. He had a brother who migrated north earlier to start up a pressing business, and that was the connection that drew him to New York City. When Bob was six years old the entire rest of his family moved north and settled in the Bronx. Bob’s recollection of his early time in the City revolves around the environment and play.

“I remember piles of snow. And we used to throw snowballs and stuff when I was six years old. And I remember they used to use a lot of char- coal? Charcoal! It was a lot of charcoal that we used to use. I was famous for running. I was one of the fastest runners in New York City. And my Brother- his gift was, he used to jump over cars!” 9

Because he spent the majority of his school and adolescent years uptown, Bob asserts, “I’m a Bronx boy!” Growing up in the Bronx and later working in Harlem, Bob’s path crossed major historical figures of the era. He met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Maxine Sullivan and the “jazz people” who gathered around Freddie’s. Bob also recalled meeting Malcom X:

“I didn’t have a chance to really talk to Malcom

My mother sent me to my Aunt’s house to get some something from her. And I didn’t know it was butter in there or something or whatever. It was summer time. And Malcom was speaking. And I’d heard about the man, but I didn’t really know that much about him. So I listened to him, and I got home late. I got home late. And when I got home, my Father said, “Where have you been? Go in the room.” [laughs]Yeah. So, ah… Malcom made an impression on me. [laughs]”

Despite the whimsical telling of this tale, there is a serious edge to it, that would later manifest in Bob’s radical efforts to reclaim SDR Park. While Bob’s associations with jazz musicians and African American leaders in the Civil Rights were influential, his immediate family was foundationally formative. Another memory from Bob’s childhood involved coming home to a house full of neighborhood kids. “My mother was always involved with kids” he recalled, and as if following in her footsteps, when it came time for Bob to choose a career, he invested in social work focusing on children. Later in life, at the funeral of an aunt, he made the discovery that seven members of his extended family were active social workers. “So it’s a thing in my whole family… I guess this was just in my blood.”

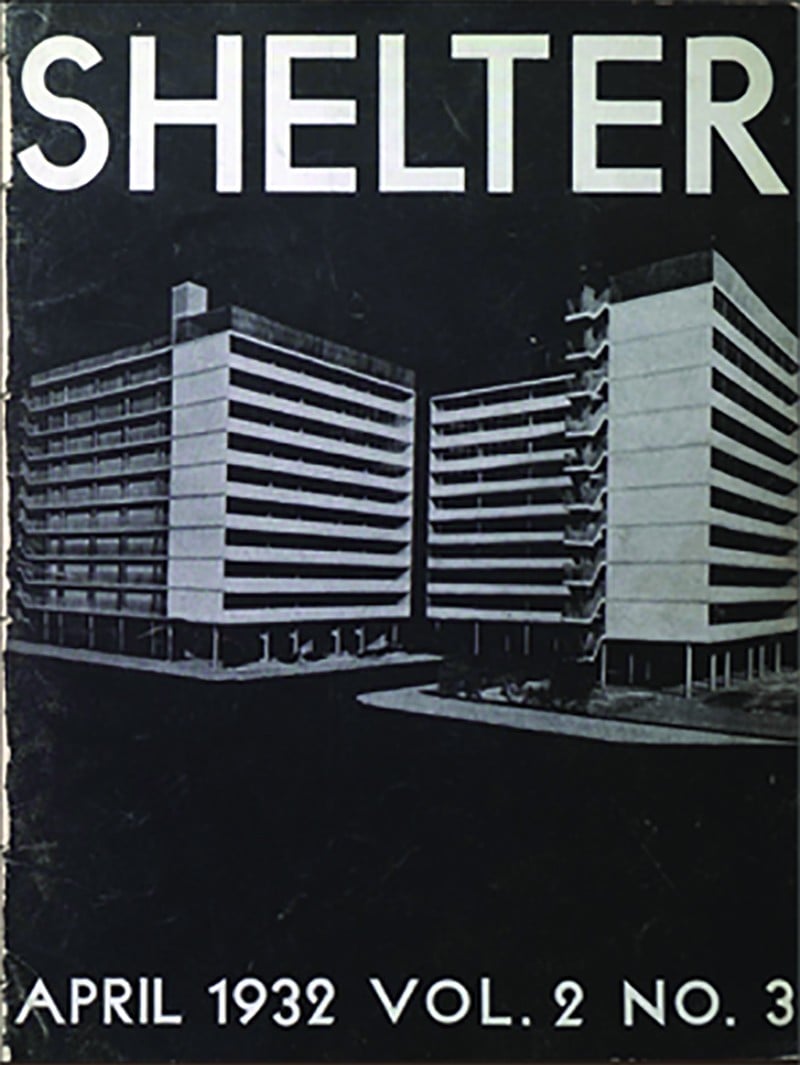

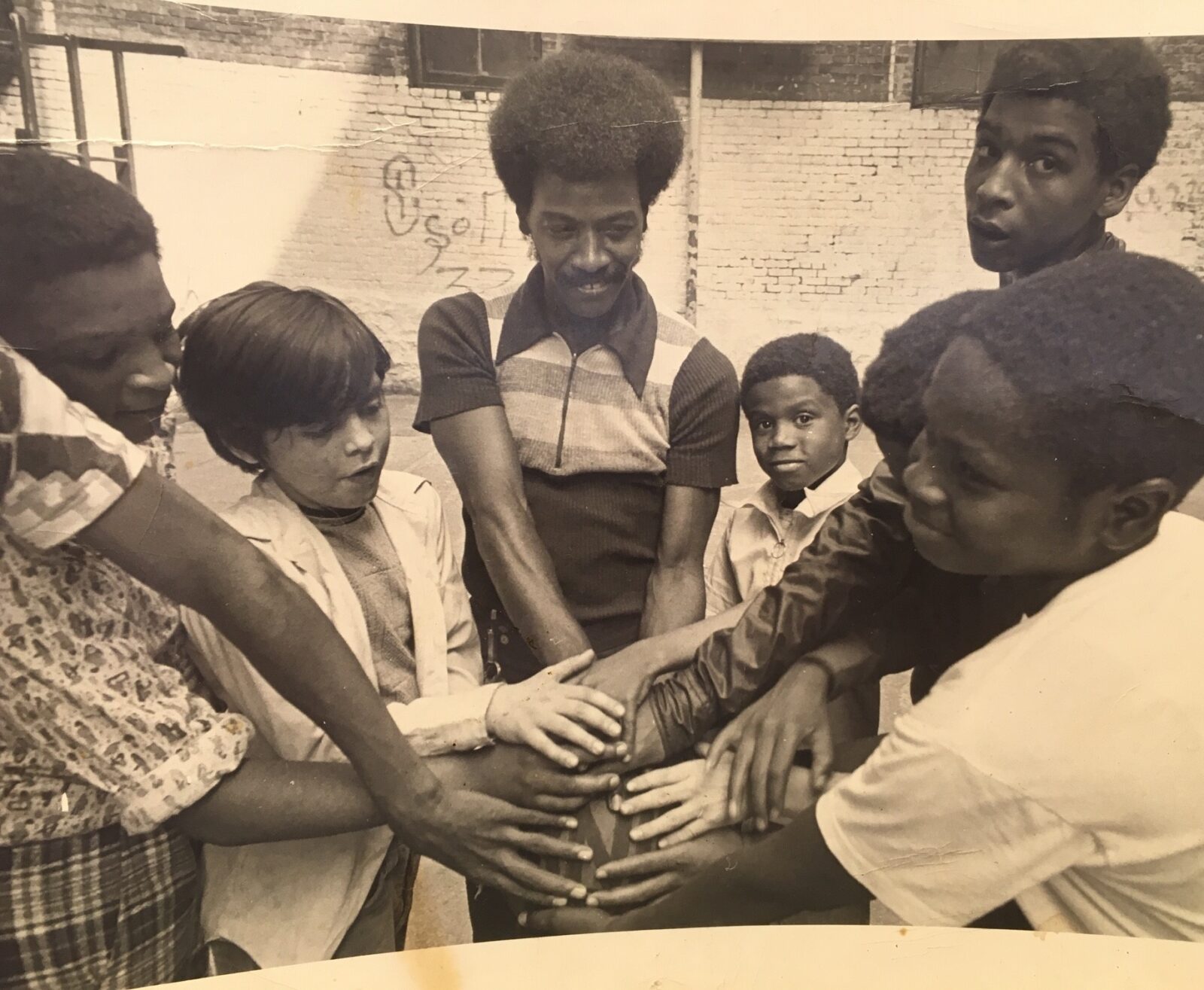

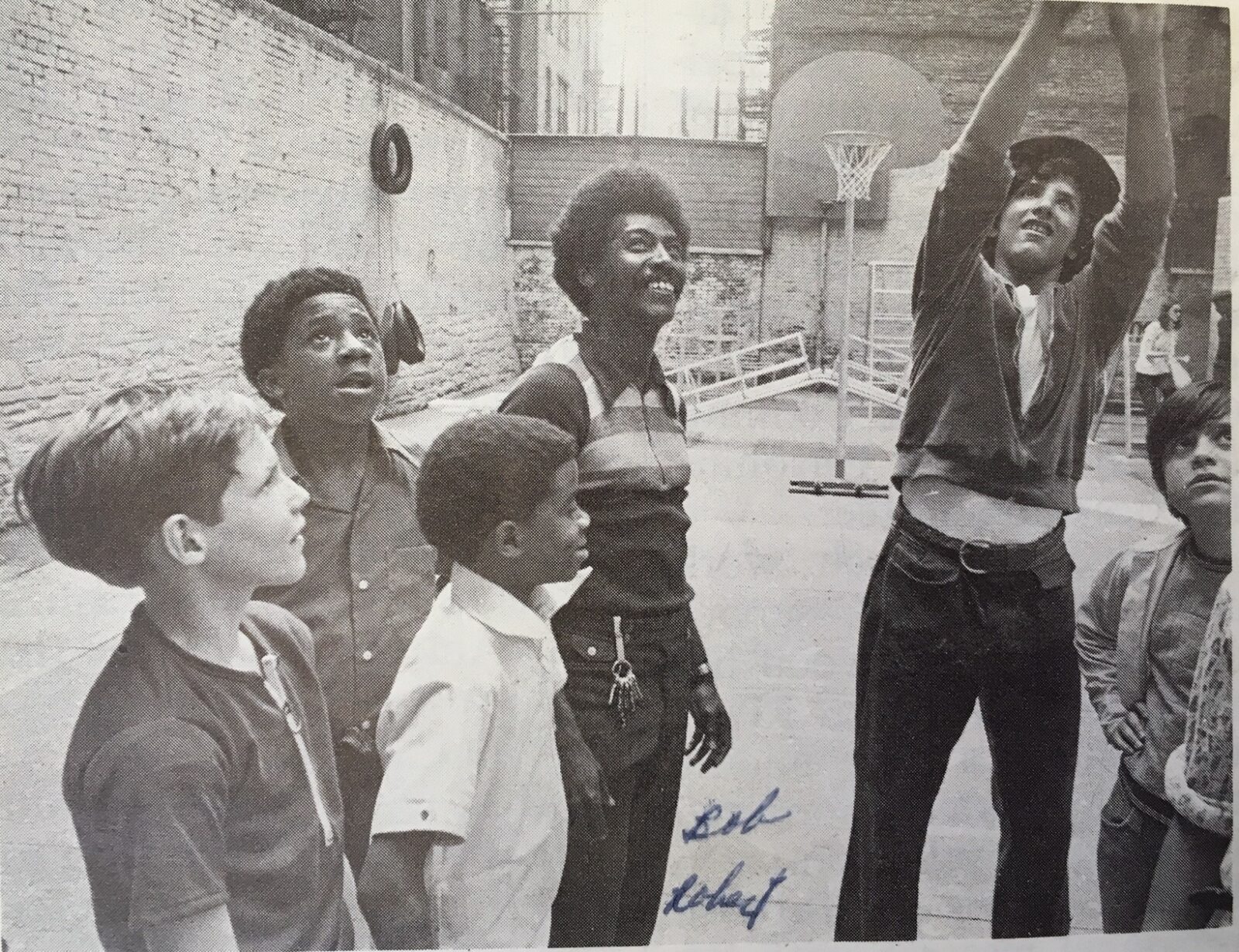

Image Left: Bob and Students at the Sloan Center for the Children’s Aid Society, 1972. Photo credit: Maury Englander, CAS Annual Report

Bob began working with children in Harlem and later accepted a position from the Children’s Aid Society as a Special Education Teacher responsible for boys programming downtown. This brought him to the Lower East Side where he organized basketball games, trips to sporting and cultural events, led classes, and worked with individual children. In the process, he built lasting relationships with families and members of the Lower East Side community and became a surrogate father (and later grandfather) to hundreds of kids from the neighborhood. Nearly every aspect of this work traced back to SDR Park. Initially Bob could not deny how degraded the seven blocks of park space had become. The following excerpts from his oral history reveal both his observations and his tactics for reclaiming the park.

It used to be a mess.

There used to be a dumping ground where they’d bring in mattresses and refrigerators and stoves and just dump them in the park. Everything- just dump it here. It was a dumping ground.

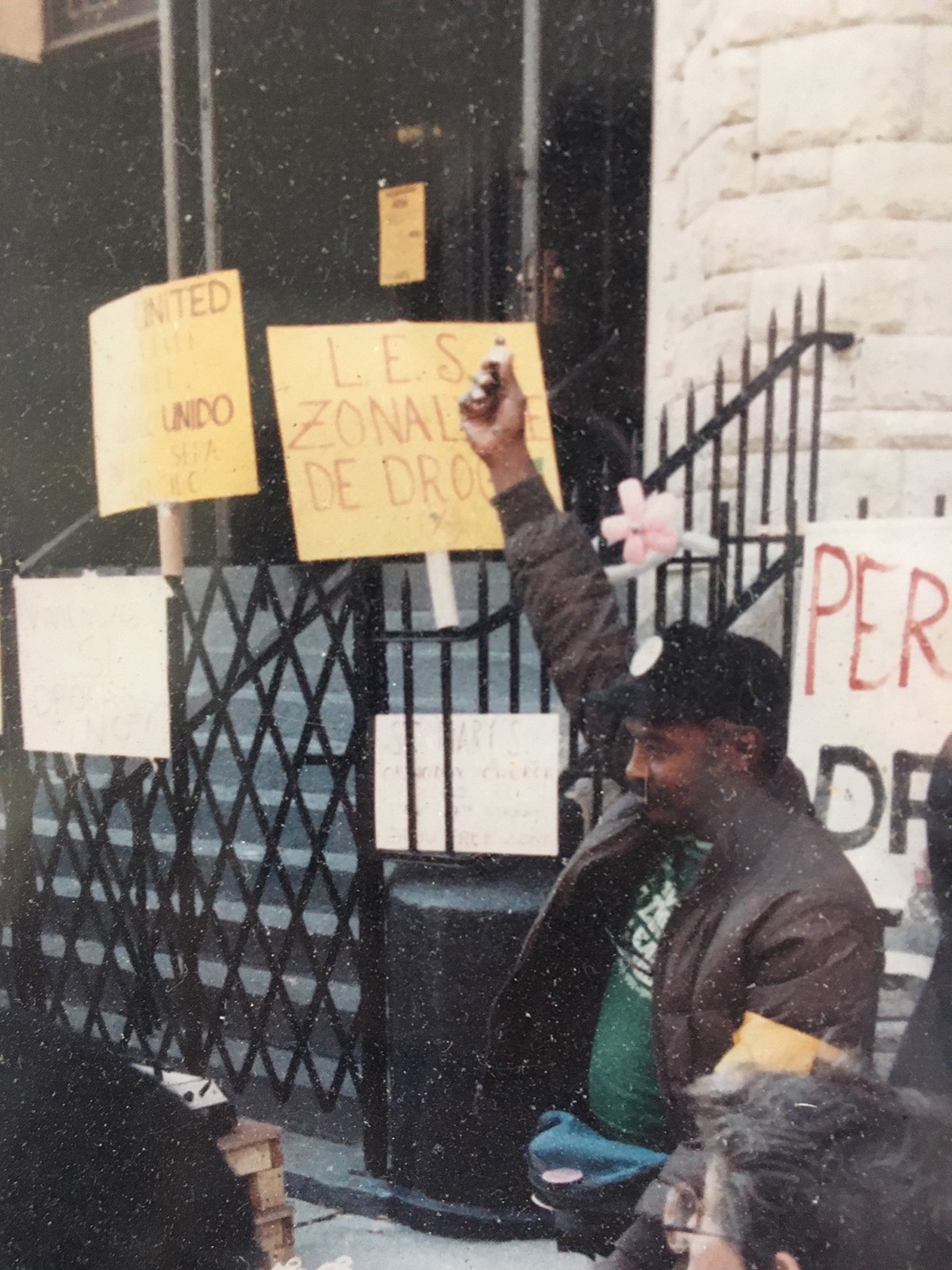

I took an interest in this park because I would meet the kids over here. And it was a rundown park at the time. It was drug infested and, I started a group called DFZ- Drug Free Zone. And I would put up banners. And wherever that banner was at, the kids would play in that area. And the drug dealers knew not to mess with that area.

Matter of fact, one guy told me, he says, “You are the only guy I know that the gangs respect you. All the gangs.” I said, “Yeah!”

It was really quite a time. I- I could remember taking kids to ball games, and some of the drug dealers, I’d say, “Hey I need some money!” [laughs] I’m serious! Two or three hundred dollars they give me. Because they knew I was going to spend it on the kids. We’d go to ballgames and I had money to pay for hotdogs and everything else from them. The thing was- the connection was- I didn’t want them selling in here in the park. And once I made the connection with the big guys, their little workers didn’t want to be known for messing up my program here with the kids. So that worked. It worked out very well.

And we um, we formed a good relationship with the precinct. I used to go to all their meetings… I was very interested in what was going on… Of course at the time, the kids were turning away from the police. Because this is going back to the time before King got killed… kids didn’t trust the police. So I was like a buffer between them. I was letting them know there were some good police officers. And they became friends with them.

I had police officers who used to come after work or before work and hang out with the kids. They would help them with their homework.

My method- it’s so different. And I wouldn’t advise anyone else to try to do the things that I do because I’ve done this so many years… A guy had a gun at, at my head one time. He said, “You’re crazy aren’t you.” He said, “You know I could kill you right now?” I said “Sure you could.” I said, “That’s the object of you having a gun there.” And he said, “You’re nuts. Later.”

Bob’s understanding of neighborhood power dynamics was acute. Everyone from the community- be they pregnant mothers, local activists, Parks officers, artists, dealers and users of drugs, police, homeless people, punk teenagers, hippies- were enlisted to help Bob reclaim the park for the children. Putting the kids at the center of the issue enabled him to build a radical coalition of unlikely players. The lasting outcome of Bob’s method challenges and complicates popular narratives that vilify drug dealers and users, dehumanize the homeless and sex workers, and position the police in aggressive oppositional relationships to People of Color. In summarizing his position in the community, Bob declared with a chuckle, “I became a forceful man, without any power.” Arguably, Bob established himself as a leader with tremendous power- albeit none of that power was officially granted. For instance, Bob didn’t have the official power to close streets for children to play, but that didn’t stop him from blocking off Forsyth Street the street between Delancey and Rivington and standing his ground against the police when they attempted to shut him down. Oddly enough, a singular moment of powerlessness stands out as a turning point for Bob in his relationship with the park.

Photo Right: Bob and Students at the Sloan Center for the Children’s Aid Society, 1972. Photo credit: Maury Englander, CAS Annual Report

I was on the basketball court right there. And I had a bunch of kids with me down there. At that time, I played a lot of basketball. And I knew every inch of the court because- part of it was sand. And we used to run people into the sand. You kind of [makes the gesture of pushing someone aside by the shoulder]. That was part of our little thing. This guy came in with a gun. He was shooting like crazy. One of the bullets hit the pole, and you hear ‘peew’!

I hit the ground. And I got up. I was so angry. The guy had left and I was so angry. And I said, “We got to do something”. I said “Tomorrow I’m coming out here and I’m bringing my dogs and I’m going to clean up this [lowering his voice] fucking park. And I came down the next day, and I got the police involved, and I told them, I said “This has got to stop.” I said “The kids- somebody could have really got hurt. That bullet could have come- you know, it hit the pole and could have killed anybody.”

That was a turning point. Right there was the turning point

After this moment, Bob, along with his Dobermans, Oyan, Kenyatta, Kendu, and Bo mobilized the entire community to restore the park block by block. The very nucleus of his effort was the block bound between Delancey and Rivington- the area known today as M’Finda Kalunga Garden. Bob started this project without knowing much about gardening. He committed himself to learning from a team of gardeners- people from the community who shared a passion about making SDR a safe park for the neighborhood.

“I used to have barbeques and stuff in here. I took over this area. There was nothing in here. I used to bring my dogs in here and let them run around.

I took over this garden, and a lady named Thelma- she’s still around- she helped me. She did a lot of work. Didn’t know one plant from the other, you know. I came in with a lady who was going to give us some donations- Jim Pender and I. And she was giving me all these Greek terms and all- you know. And I said, “Oh that would be nice, that’ll be nice” [laughs]

I wanted a garden for the kids to come and learn- not just play. I want them to know that they could go to other parks, but this is THEIR park.”

Image Left: Bob at an anti-drug protest, circa 1980’s. from the collection of Bob Humber

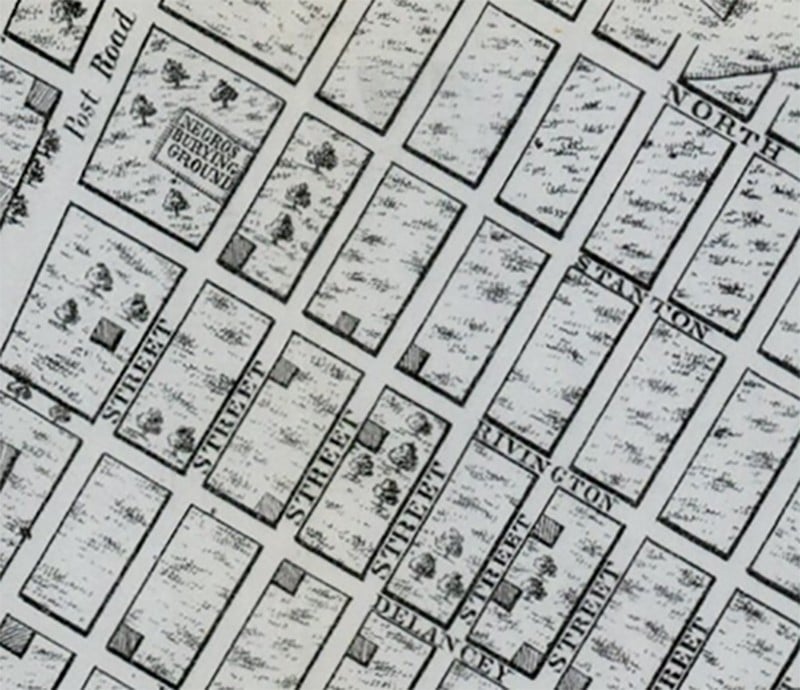

Bob’s own education grew beyond a knowledge of plants and gardening. The land itself became of interest to him, and through this Bob learned about the African Society’s burial ground. In 1794 after the first African-American Burial Ground was closed, the African Society petitioned the City to allot them a place to continue to bury their dead. “The free People of color”10 of this group, with the support of Trinity Church, raised the funds to purchase a 50 by 200-foot plot of land on the west side of First Street (Chrystie Street today) between Stanton and Rivington. The cemetery was opened on 1795 and remained active until 1853 when burials were banned in Manhattan. It is nearly impossible to know how many African Americans were buried in the Chrystie Street Cemetery. The allotted space could accommodate 1,950 graves, though vault clearing practices common at the time suggests there may have been a great deal more.11 Within a year after the cemetery was closed, the site was divided, sold and developed. The buried were exhumed and reinterred at Cypress Hills Cemetery12 and life went on downtown without any place to gesture to the African Americans who lived and died in New York City during these early years.

Bob said, “I knew about it. I always wanted to represent it in some way.” With the garden now a focal point of his park efforts, and its location being only half a block away from the original site of the Chrystie St. Cemetery, Bob had the representative space he’d been seeking. Bob’s next objective was selecting an appropriate name.

“We did some investigating, and we got this guy from Long Island University, I believe it was. And he gave us several names, and we picked. We picked this one, because it meant ‘Garden At the Edge of the Earth’, and at that time it seemed like the edge of the earth. This garden really felt… it was different. And each year I try to add something different. I brought in different people. I wanted a garden that would be for EVERYONE- not just for, people with money.”

Image Right: Excerpt from the 1797 Taylor-Roberts Plan for Manhattan, BLR Antique Maps

The name M’Finda Kalunga is in the KiKongo language- A Bantu-based language spoken across a region of Africa encompassing the southern part of the Republic of Congo, the southwestern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the northern part of Angola.13 A large percentage of the enslaved people brought to America originated from this region. This added layer of historic context deepens the commemorative power of the garden. In 1982 when the name was chosen, the garden represented the resilient and restorative power of the community; and as a commemoration M’Finda Kalunga Garden not only represented the second African American burial ground, but the lives of the men and women who were brought to New York City during the period of chattel slavery in the United States.

At the very intersection that Robert Moses fought to have closed in 1934, M’finda Kalunga Garden thrives, inspires and grows more vibrant with each passing year. Surrounded by plants and flowers (roses being Bob’s favorite despite his allergy to them), the many garden benches offer a place to sit and reflect over the long and contentious history of what is today known as Sara D Roosevelt Park. The results of Bob’s groundbreaking work obscure the decades of decline and unrest just as the new housing developments continue to erase the physical traces of Lower East Side history. All of this change and progress has one particularly curious manifestation: Bob was priced out of the Lower East Side about fifteen years ago. In this respect, he has become a part of the single most continuous historic narrative for this track of land: displacement. Ultimately Bob moved uptown to East 94th Street, yet he continues his work on the Lower East Side. Each day Bob makes the commute downtown to tend the garden (except for the roses) and offer aid the homeless. Despite his economic displacement, Bob continues his activism with his unique blend of compassion, hope, and by any means necessary approach. In this way looks, he forward to future of the garden he founded and the park he worked to reclaim.

“Yes there’s always a different issue come up. For instance, it used to be heroin was king of Sara D Roosevelt Park, then it came to be crack. And they keep pushing these drugs out here. And the poor… innocent people are thrown into these traps. [But] I’m excited about the future of the park. I think that what I’ve done- I’ve worked with the younger generation and as they get older, they respect what I’m doing. And they’ll respect this park more. This is a great park.”

Image Left: Bob Humber in his Office at BRC Senior Center on Delancey Street, 2020

Footnotes:

1 The Tenement House Exhibition, Riis, Jacob. Harper’s Weekly 1900 p.104

2 City Moves Today In Housing Project, New York Times, Friday July 12, 1929

3 Informal Report, Seward Park Librarian, 1930. The librarian notes “The long projected development on Chrystie and Forsyth Streets has been started, and the houses have been torn down from Canal street, north. This has meant much moving about.” The librarian refers to displacement statistics complied by The Chamber of Commerce.

4 Backs Housing Plan for Chrystie Area, New York Times, Thursday March 3,1932 *****21

5 Model Housing, New York Times, Friday March 4, 1932. The quote is quoted in the article from a member of the Chamber of Commerce

6 LaGuardia Scraps Chrystie St. Plans, New York Times, Thursday, February 1, 1934, L+21

7 IBID NYT 2.1.1934

8 Informal Report, Seward Park Librarian, 1935

9 Oral history interviews of Bob Humber by Jason Eisner. Recorded on February 3 and 12, 2020. All transcribed excerpts are sourced from the February 3rd recording.

10 Memorandum: 235 Bowery Street, Block 526/Lot 12, Manhattan Archaeological Field Investigation, Historical Perspectives Inc. 4/9/06 p.2

11 IBID Historical Perspectives Inc. 4/9/06 P.4

12 Pike and Allen Street: Center Median Reconstruction, Phase 1A Archaeological Documentary Study, AKRF Inc, January 2010, pp.23-24

13 Survey Chapter: Kikingo-Kituba. Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures Online https://apics-online.info/surveys/58