Fanny Rogarshevsky

Fanny Rogarshevsky

The oldest photograph of Fanny Rogarshevsky in the Museum’s collection dates to one of many transformational periods in her life. In this studio portrait, roughly dated between 1917 and 1918, Fanny wraps an arm around her youngest child, Philip, who stands on a step so that he is nearly as tall as his mother. Their gaze is focused at something beyond the picture frame to the right. Fanny appears confident, with her hand on her hip.

At the time the photo was taken, Fanny’s husband Abraham was in the final year of his battle against tuberculosis, too sick to work. Between maintaining a kosher home, keeping after Philip and Henry to do their homework, shopping and cooking meals, washing laundry, balancing the family budget, and nursing her husband in is final days, it seems likely that Fanny had little time for reflection. Indeed, to the extent that it is possible to draw such conclusions from studio portraits, Fanny’s countenance suggests a forward-looking determination.

But looking back into Fanny’s past does help us interpret her life in this transitional moment. Museum researchers conclude that Fanny was born in Vilna, Lithuania in 1873. Her name at birth was Zipporah Bayard. She married Abraham Heller, and they started a family. In 1901, the family left Russia for America.

Why did they leave? Fanny’s grandson, Irving Cohen, shed some light on the question. When he was asked, “Did your mom or your grandmother ever talk about where they were from in Lithuania?” Irving replied, “Never… Because they didn’t have it good in Europe. They ran away from Europe.” Religious persecution in Russia drove entire families like the Rogarshevskys away from their homes. Irving’s recollections seem to suggest that Fanny made a conscious choice to avoid talking about painful memories.

In July 1901, the Heller family arrived at Ellis Island. They numbered eight; Fanny, Abraham, and six children: Bosse, Estr, Moishe, Scholem, Heinde, and Taube. Taube and Hinde were both 6 months old at the time. Fanny claimed they were twins, though Taube was in fact her sister’s daughter. Fanny’s sister died in childbirth and the Rogarshevskys adopted the child, bringing her with them to America. Upon arrival, Abraham changed the family surname to Rogaszewsky- the name of the uncle who adopted him (of the myriad spelling variations, Rogarshevsky is the most recurring).

July 1901 found the Rogarshevskys in the Jewish Quarter of a new country with a new name. Within a year, Fanny became pregnant with her sixth biological child, the seventh child in the family. In the early 1990’s, Museum Founder Anita Jacobson spoke to that child, Henry. He mentioned that he was born in 1902 “across the street;” researchers learned from other oral histories that “across the street” meant Orchard Street north of Delancey. This suggests that shortly after arrival, the Rogarshevskys put down roots on Orchard Street. With the family growing, perhaps everyone was focused on leaving the past behind and starting over.

But even if Fanny was reluctant to share memories of life in Russia, she showed no restraint in preserving the Jewish traditions she grew up with. New York City- the Lower East Side in particular- represented a new start and a chance to practice her faith without fear of persecution. So, it must have come a shock to her when only ten months after her arrival in New York, the price of kosher meat jumped from 12 to 18 cents per pound.

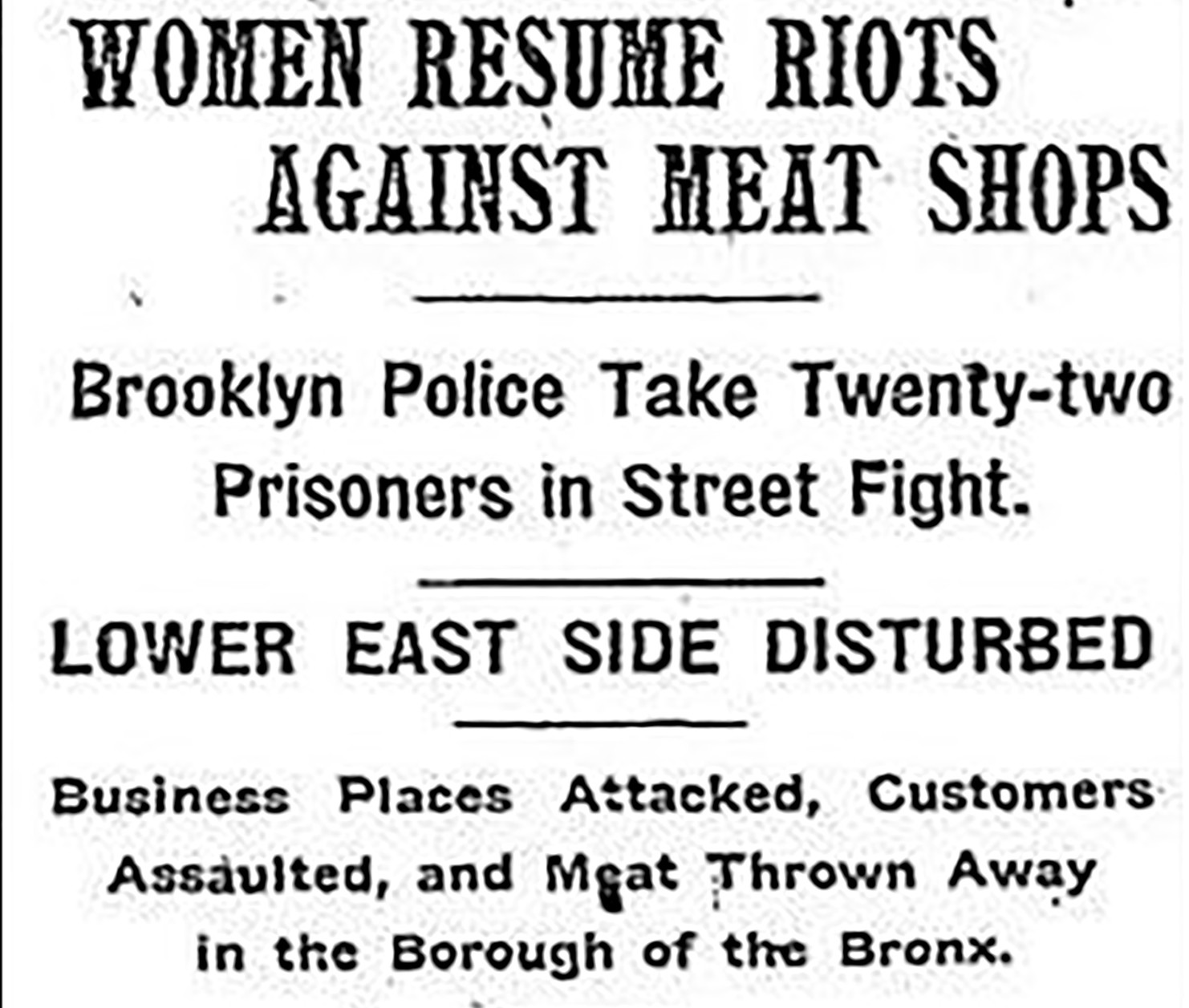

Fanny likely felt a maternal obligation to maintain the religious life in the home. To Jewish housewives, the newly inflated price of kosher meat posed a direct threat to those responsibilities, and they saw it as an attack on their religious freedom. Channeling their outrage, Jewish women rose up in protest against the Meat Trust. On May 15th, tens of thousands of Jewish mothers across the boroughs stormed their neighborhood streets, confronting police and setting meat on fire, demanding an end to the price hike. These formerly apolitical housewives adopted the language of labor unions, calling their action a ‘Strike’ and labeling anyone purchasing kosher meat during the boycott a ‘Scab.’ After days of rioting, and a sustained citywide boycott, the Trust reduced the price of kosher meat to 14 cents.

However, sorrow was never far away for the Rogarshevskys. Missing documents make it impossible to know when Fanny lost her children, Heinde and Taube. Oral history accounts from Henry and from Morris’ wife, Evelyn Rosenthal, state that both children died of diphtheria. By the 1910 census, on which the Rogarshevskys first appear as residents at 97 Orchard, Fanny is enumerated as having given birth to 8 children, 6 of whom survive. Heinde and Taube passed away sometime between their arrival in 1901 and their residence at 97 Orchard by 1910. In this loss, Fanny was not alone. The 1910 census reveals that ten out of the eighteen mothers living in 97 Orchard suffered the loss of one or more children.

The 1910 Census also enumerates Abraham as being unemployed for 13 weeks, suggesting that the family was struggling financially and that Abraham may have already been in declining health. On July 17, 1918, Abraham passed away from tuberculosis.

The second oldest photograph of Fanny in the Museum’s collection is another studio portrait. It is labeled “Fanny as Widow.” Depicted alone in a dark, nondescript space, Fanny is focusing her attention slightly to the left. What is she thinking about as she poses for this photograph? What new direction will her life take her as a single mother?

Irving Cohen (pictured below) recalled visiting his grandmother more often on Shabbos after his grandfather passed away. These memories paint a portrait of Fanny’s later years and provide key details about how she persevered.

“I never knew the landlord. I know he was a very nice man when my grandfather died—he told Grandma, “you take care of the building, you don’t have to pay rent.” And she made an agreement with him. She hired some Irishman to clean the building and everything, and she took good care of the building.”

Abraham Rosenblatt, the owner of 97 Orchard Street in 1918, indeed employed Fanny as the superintendent of his building. Rosenblatt was also of Lithuanian origins; he came from Kovno, the same town as Fanny, and perhaps their shared roots played a role in his desire to help her. By the 1920 Census enumeration, Fanny is listed as “Janitress” for 97 Orchard. She maintained this position even after the building was sold to Moses Helpern. In this position, Fanny got to know the residents- regardless of how long they remained or where they immigrated from. She earned the respect of her neighbors, and Irving noted, “Everybody, when they spoke of her, called her Mrs. Zippy.”

“In the backyard… there used to be toilets… And the bummers would come in, and they wanted to use it, and she would yell at them, “Get out of here, you bums!” in her accent, she wasn’t afraid! Oh, no, you think she’d be afraid of them, not her! Not her, she was a tough old biddy.”

In one of the last photographs taken of Fanny Rogarshevsky at 97 Orchard, she is standing on the roof. Unlike the earlier studio portraits, she is staring directly at the camera. The photograph was taken sometime during Fanny’s residency as “Janitress,” between the 1930s and 1941, when she finally left 97 Orchard Street to live with her son and daughter-in-law. She had seen countless residents come and go, and was herself one of the last residents to live in the building. In the photo, with her hand on her hip, and confident stare, it is easy to understand what Irving meant when he called Fanny a tough old biddy.

Unlike her children, there is no record indicating Fanny completed the process of acquiring American citizenship. This did not mean she was without agency or a political point of view. Her choices were at once deeply personal and political. As a woman whose obligations included keeping a kosher household, Fanny may have joined the street protests to draw attention to the impact of the inflated prices of kosher meat. As a single mother who kept her family together in the absence of a male breadwinner, Fanny became the respected and fearless “Janitress” of 97 Orchard Street. That she befriended her neighbors regardless of their history – the religion they practiced, the language they spoke, or their place of origin – suggests that while Fanny was a woman of her moment, grounded in the present, she kept her focus on the future, not dwelling much over the sorrows of her past.