This is part three of a four-part series documenting the search for the grave of 97 Orchard Street’s first landlord, Lucas Glockner, in Green-Wood Cemetery, a 478-acre cemetery in Brooklyn that opened in 1838. Read part one and part two.

Great Reads

Dead and Buried Part III: The Found

July 15, 2020

After a quarter century of cultivating street smarts in New York City, I’m shocked to hear myself say, “This street is always pretty deserted, I think we’ll be safe.”

It’s early Monday morning. With social distancing in mind, my partner and I are searching for a less crowded sidewalk on our way to the offices of Green-Wood Cemetery.

From the stroller my daughter says, “Guys!” pointing out clusters of men gathered at the intersection. They are making small talk while waiting to be picked out for a day’s work. “Essential Worker Guys,” I reply as we cross Fort Hamilton Parkway, westbound on 37th Street.

With the cemetery expanding to our right and a transit service station to our left, our pathway is deserted. Along the way we encounter only five living human beings – one of them fully covered in a Tyvek suit. She stepped out of a driveway to wave a bus into the service station for cleaning. To explain the woman’s unusual appearance, my partner says, “Essential Worker.” Unfazed, our daughter is accustomed to seeing people concealed by masks and protective gear – it is now a part of growing up during a pandemic.

My thoughts drift to these Essential Workers, life during crisis, and Lucas Glockner, who we hope to locate somewhere in that pastoral expanse of Green-Wood Cemetery.

“97 Orchard Street was built by Lucas Glockner in 1863 when the neighborhood was known as Kleindeutschland – meaning Little Germany.”

I’ve spoken some iteration of this sentence for a decade, but this morning I feel ill at ease about it. Glockner was a tailor. What did he know about framing houses, plastering walls, hanging doors, or laying brick? Glockner paid skilled crews of Essential Workers to build his tenement. Who were they? We can only guess, since the Museum has no record. The Essential Workers of history remain obscure, though their work often makes history possible.

Were these workers immigrants from the German States, as Glockner himself was? Were they Irish? Were they African American? Did they have to travel far to get to their worksite? How did their homes compare to the house they were building for Glockner? On February 23, 1863, when Glockner and his partners purchased the Second Reformed Presbyterian Church, America was in the midst of the Civil War. Away from the battle fields, as people tried to maintain a ‘normal’ life, fear and uncertainly lingered in the shadow.

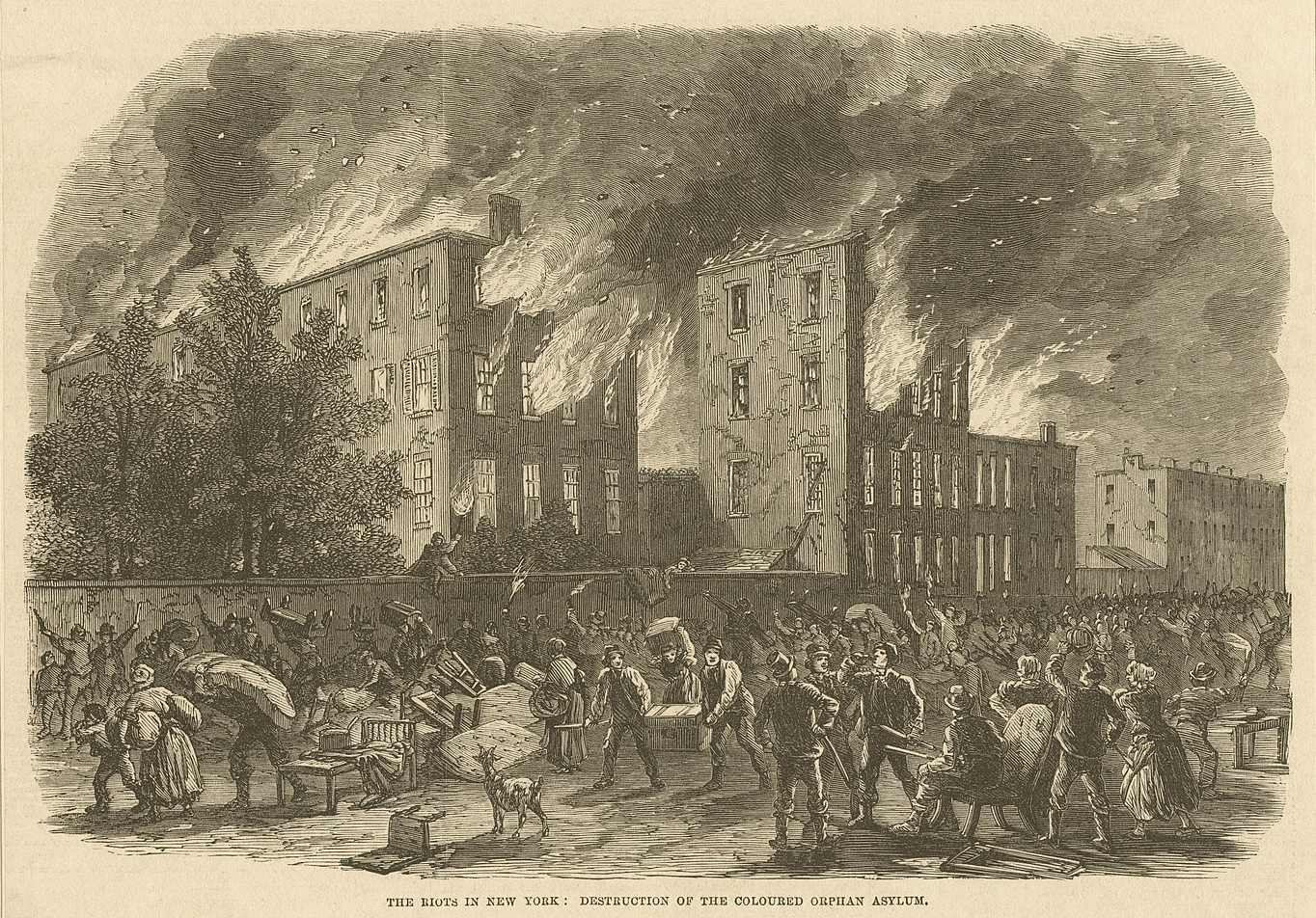

On July 13, 1863, New York City itself became a battlefield. A draft was issued to supply the Union Army with more soldiers. Weary of war, fearful at the prospect of conscription, and enraged by a $300 provision allowing the upper classes exemption from the draft, members of the white working classes took to the streets in protest.

What began as a massive demonstration against the draft, exploded into days of arson, looting, and violence. In the chaotic rage of rioting, African Americans emerged as the target of violence. A week of being hunted and murdered in the streets, fighting their way out of burning buildings, and abandoning their homes and businesses, left Black New Yorkers feeling profoundly dislocated and traumatized, manifesting in widespread displacement.

If there were African Americans in the crew of Essential Workers constructing Glockner’s tenement, how did they safely navigate this violence to work and home during the Draft Riots? Did they attempt to go to work at all? Did some of them leave the first day and never return? I wonder to what extent they were welcomed in Kleindeutschland at all – even before the riots. One of the many things that violent week exposed was America’s legacy of anti-Black racism.

Whoever the workers were, Glockner’s tenement was in some phase of construction when the Draft Riots began. Perhaps in addition to experiencing the collective anxiety caused by the riots, Glockner was also concerned about the security of his investment. That skeleton of a building represented a new direction for his life and cost him years of savings. For Glockner to lose it as collateral damage of the riots would have been a major setback. Ultimately, the violence and destruction in Kleindeutschland was mild compared to other parts of the city, and thus, over time, Glockner saw tremendous return on his investment. A happy ending for Glockner, but I can’t help but consider what role race played in his success.

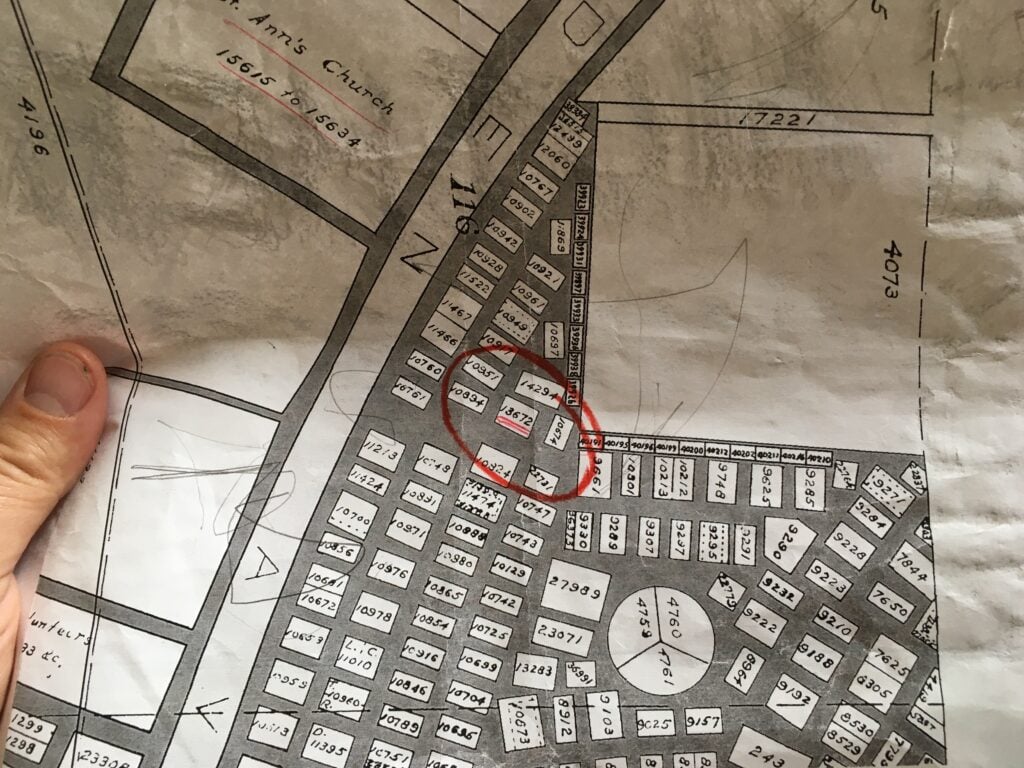

Green-Wood’s majestic main gate interrupts my thoughts. Before us are huddles of people dressed for mourning. A worried-looking priest gazes compassionately at every passerby. Entering the office, I explain my mission- to find the grave of Lucas Glockner to a very busy man named Jhon Usmanov, and I am told to try the digital kiosk while I wait. “You might get lucky.”

The kiosk offers me no hope. Maybe Glockner isn’t here after all.

Quite suddenly, Jhon is standing before me, waving a sheet of paper. “I found your guy! Follow this map. On the back are the names of the people buried in the lot. But let me warn you… if you find the stone, it may have nothing on it. No names. Nothing.”

Dizzy with excitement, and closer to completing my mission, I step out of the office into the morning sunlight.

Stay tuned for Dead and Buried Part IV: The Remembered, coming soon…

Image Credit: Newspaper illustration published in the Illustrated London News, depicting flames and black smoke pouring from the broken windows and crumbling walls of the Colored Orphan Asylum, which was burned and looted on the first night of the Draft Riots, July 13, 1863.