Join us as we discover the origins of your favorite (or least favorite) holiday food traditions. This four part series will unwrap the ways these traditions have become integrated into our culture and helped shape our American identities.

Food History, Great Reads

Digging Up the Roots of Holiday Traditions: Hanukkah

Flip through the calendar and you’ll find a dozen or so special days marked holidays, but December is the month that reigns supreme among them. This month is so special that it is simply referred to as “The Holidays,” which includes Hanukkah, Christmas, and Kwanzaa, all within rapid succession of one another. So what makes this time worthy of its distinction?

For many, the holidays are a special time to slow down and gather with our loved ones. The COVID-19 pandemic has made it so that this year we will not be able to gather in the same ways as before. Big raucous family dinners will be replaced with multiple intimate affairs converged over Zoom. This adjustment may be difficult for some to make. But the way to ensure that these holiday celebrations continue to embody the spirit of those past is through the food we make.

While things may not be “normal,” our holiday food traditions can be relied on to connect us with our distant family and personal histories. The act of sharing a meal and participating in tradition-based rituals helps reinforce our sense of identity and acts as a way to practice shared values. This series will uncover the origins of various holiday food traditions to understand how they constitute our cultural identities today. We begin our journey with Hanukkah.

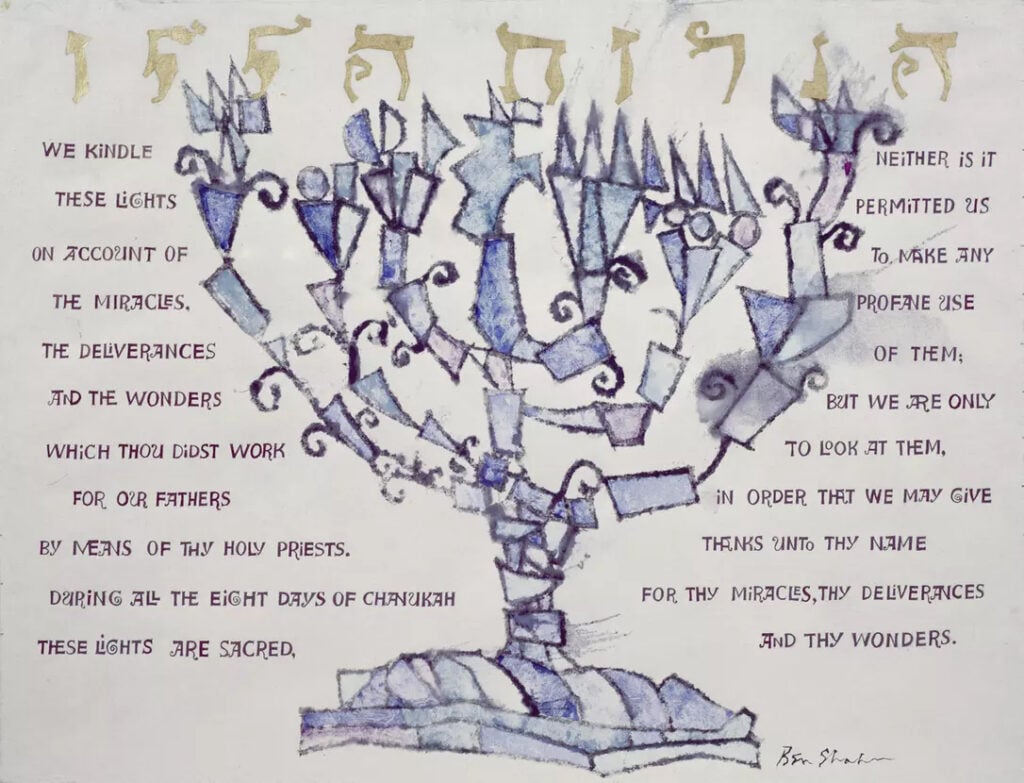

“We Kindle These Lights (Hanukkah)” 1961, by Ben Shahn. The Jewish Museum

Whether you observe Hanukkah religiously or not, its story carries important messages that are relevant to all. The story of how Hanukkah came to be one of the most prominent Jewish holidays is one of immigration and the freedom to practice religion openly. Rowan University historian and author Dianne Ashton, wrote in her book Hanukkah in America, “the celebration of Hanukkah in the center of the modern Jew’s capacity to bolster one’s own self-respect while living as a minority.” Hanukkah can be understood as a holiday that helps secular American Jews assert their Jewish identities.

For the non-religious, when people think of Hanukkah the first thing that comes to mind is latkes, menorahs, and maybe jelly-filled donuts. A quick Google search using the terms “Hanukkah” and “Hanukkah food” proves this point. What many people might not know is that latkes and sufganiyot (jelly-filled donuts) are part of the Ashkenazi Hanukkah spread. Ashkenazi Jews hail from Eastern Europe, whereas Sephardic Jews are those from the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and North Africa.

Given the diverse profile of Sephardic Jews, the types of fare that make up Sephardic Hanukkah cuisine varies. Those that have immigrated to the U.S. have taken the tastes and recipes of their ancestors with them. For example, Jews with Morrocan roots prepare stuffed vegetables, couscous, and lentil dishes typical of that area. Of Sephardic Mediterranean cuisines, chef and cookbook author, Joyce Goldstein says, “By and large, Italian Jewish food is Italian food, Jewish food from what was the Ottoman empire is very close to Greek and Turkish food, and Jewish Moroccan food is Moroccan food.”

A common thread between Sephardic and Ashkenazi Hanukkah food is the importance of oil in cooking. The oil used represents the miracle that a small jug of oil that should have only burned for one night lasted eight nights. Instead of latkes Spanish Jews fry up keftes de prasa, leek fritters, whose main components closely resemble that of potato latkes. They are accompanied by a smear of yogurt and an olive chaser.

A Syrian version of keftes de prasa includes allspice, cinnamon, and hot pepper, but leaves out the breadcrumbs. Greek Jews prepare fritadikas de quezu, which are fried cheese balls made with feta cheese, farmers cheese, egg, and flour. Cassola, fried ricotta pancakes, is a lesser-known cousin of latkes with Italian origins. This dish came to Rome in the 13th century after Sephardic Jews were expelled from Spanish controlled Southern Italy during the Inquisition. Before potato latkes came onto the scene, cheese latkes like cassola were the prime choice.

While the savory foods vary wildly, the kinds of sweets consumed share more similarities in form and makeup than they have differences. Moroccan Jews eat sfenj instead of sufganiyot. In Libya, sfenj go by the name sfinz. They may be fried in various shapes, such as rings or puffs. Though they are always made using a sticky, unsweetened leavened dough that is fried and coated in honey or sugar. Though, bumuelos or bimuelos are prepared by many Sephardic Jews across various cultures. Bumuelos originated in pre-Inquisition era Spain and continued to be shared as Jews migrated through Italy and onto the Ottoman Empire. Bumuelos is a variation of the word buñuelos, however, bumuelos are made from a sticky yeast dough then shaped into round balls before frying and dipped into honey. Some variations flavor the honey with orange or lemon.

These differences and similarities matter, because food goes beyond enriching our bodies. It also nourishes our souls and helps strengthen relationships with others, something we could especially use this year. The act of preparing and sharing food is one of the deepest acts of love. Welcoming a stranger into our homes to share a meal is an intimate act that suggests a desire to get closer. Sharing a meal is a bonding activity, especially during the holidays when most people set aside more time to spend with those they care about.

It is also a way of tracing our heritage and celebrating it. Looking at the varied foodstuffs of Sephardic Jews, one can marvel at how Jews have adopted their traditions to the region they resided in. They brought their traditions, continued to practice them, but flavored them with the seasonings of their locale. So while our tables may not be as full we can take comfort in the familiarity of the dishes that grace our tables. Cooking and sharing the foods our mothers and fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers, and so on once prepared and ate makes us feel closer to them and keeps their memories alive long after they have passed. Sharing and passing down these food traditions reminds us of where our ancestors have come from and is a chance to reflect on the lives that have come before ours. As countless Jewish families across America pull out their menorahs and heat the oil for fritters, they are refilling the oil that is their cultural heritage and passing the torch along to their children as they do so.

Photo: the Center for Jewish History

As countless Jewish families across America pull out their menorahs and heat the oil for fritters, they are refilling the oil that is their cultural heritage and passing the torch along to their children as they do so.

Read Part II: Christmas now!

Images:

-

Header: Tenement Museum collections

-

“We Kindle These Lights (Hanukkah)” 1961, by Ben Shahn. The Jewish Museum

-

Sephardic Leek Patties, photo: Susan Barocas. myjewishlearning.com

-

Menorah Lighting, Center for Jewish History

Sources:

-

Alhadeff, Ty. “Https://Jewishstudies.washington.edu/Sephardic-Studies/Manna-from-Heaven-Bumuelos/.” Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. The University of Washington. Accessed October 22, 2020.

-

All Things Considered. “The Oil That Fueled the Hanukkah Miracle.” NPR, December 25, 2005.

-

Ashton, Dianne. 2018. “How Hanukkah Came to America.” The Conversation. December 2, 2018.

-

Barocas, Susan. “Sephardic Leek Patties for Hanukkah.” The Nosher. My Jewish Learning, December 24, 2019.

-

Ben-Moche, Erin. “A Sumptuous Taste of a Sephardic Hanukkah.” Jewish Journal. December 5, 2018.

-

Capeloto Sendowski, Linda. The Global Jewish Kitchen (blog), November 26, 2010.

-

Dickerman, Sara. “Sephardic Jews’ Hanukkah Treats Have a Rich History, Too.” Seattle Post Intelligencer. November 26, 2002.

-

Fabricant, Florence. “Hanukkah Table: Sephardic Treats.” New York Times. 1985.

-

Francis, Dikla. “Moroccan Sfenj Donuts Recipe.” The Nosher. My Jewish Learning, December 24, 2019.

-

Hevrdej, Judy. “A Sephardic Hannukah” Chicago Tribune. December 10, 1987.

-

Green, Emma. 2015. “How American Jews Ruined Hanukkah.” The Atlantic. December 9, 2015.

-

Natkin, Michael. “Keftes De Prasa, the Sephardic-Style Leek Fritters Recipe.” Serious Eats. Serious Eats, September 23, 2009.

-

Steinberg, Liz. “From Constantinople to Ellis Island: One Family’s Secret Passover Dumpling Recipe.” Haaretz, April 20, 2016.

-

Sussman, Adeena. “Bimuelos with Honey-Orange Drizzle.” My Jewish Learning. Accessed October 22, 2020.

-

Tenorio, Rich. “Were the Original Hanukkah Latkes Really Ricotta Pancakes from Italy?” Times of Israel, December 22, 2019.

-

Underwood Varma, Jessica. “Meet the Residents: Victoria Confino.” New York: Tenement Museum, n.d.

-

“What Is Hanukkah?” Chabad. Chabad Lubavitch, October 29, 2011.